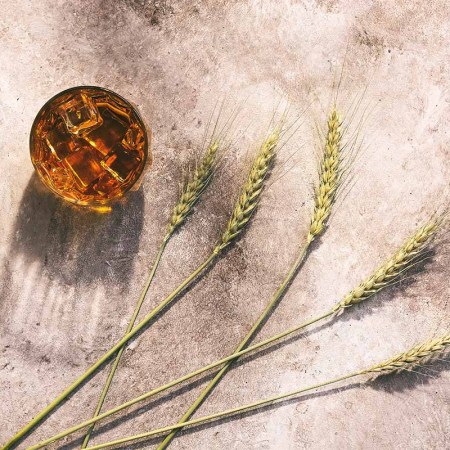

When the young Scotch whisky distiller InchDairnie launched its latest product early this year, eyebrows and legal matters arose. That’s because RyeLaw, as the drink is called, is made using rye. Rye whiskey may be quintessentially American — indeed, over the course of the last 15 years, sales of rye have rocketed, buoyed along by cocktail culture. But in Scotland, making a rye whisky is tantamount to revolutionary.

“We have no heritage to speak of, so all we can rely on to make an impression is our innovation in creating drinks with lots of flavor,” says InchDairnie’s founder Ian Palmer, who is launching his RyeLaw in the United States this spring. “Changing the cereal used is a big part of that. But this isn’t about making an American rye whiskey. This is somewhere between American rye whiskey’s very spicy, strong flavor and the softer, more sippable subtleties of Scottish malt. It very much speaks of Scotland.”

The Fife-based InchDairie is not alone. Bruichladdich, another Scottish distillery (owned by Rémy Cointreau since 2012), also recently launched a rye whisky — the first ever from the Hebridean island of Islay — following one from the Angus-based Arbikie, which in 2018 arguably started what looks to become a trend. Some eight other distilleries in Scotland are now reported to be considering a rye-based whisky.

How Ireland Is Rediscovering and Reinventing Rye Whiskey

Powers just launched a 100% Irish rye whiskey that’s refined, complex and … sexy?They all have to work with the complexities of making a rye relative to making the malt or blended whiskies more famously produced in Scotland, not least the fact that when you mash rye — which is husk-free so it sucks up liquid fast — it becomes viscous. Separating the solids from the liquids (something not typically done in the production of American rye whiskey) requires the delicate management of double distillation in proprietary stills, followed by filtration. When fermenting, it can foam up and burn in the still, too. As well, some malted barley is required to kickstart the conversion of starches into sugars.

In American distilling, it’s not uncommon to use enzymes to this end. However, this process is not allowed in the production of Scotch whisky. In short, it’s a pain. “It’s not impossible but it comes close,” Palmer says. “But this also presents an opportunity for Scottish distillers choosing to work with rye — to drive different technologies in the production of Scottish rye whisky. What’s interesting is that none of those distillers making one now are doing so in the same way.”

One reason Bruichladdich was intrigued to develop its Regeneration Project rye was to build a local economy. Company founder John Stirling got chatting with an Islay farmer who was planting rye as part of his schedule of crop rotation; rye doesn’t require fungicides or pesticides, its deep roots assist drainage and it appears to improve the health of the barley grown next season.

It might be argued that Scottish rye whiskies are more Scottish than the single malts and blends more readily associated with the country. The rye used is grown in situ — as a crop it suits the cold, dry winters and poor soils of northern Europe though still offers a different flavor and aroma profile to ryes grown in North America — whereas global demand for those malts and blends means that much of the distilling-quality barley used in Scotland has to be imported.

John Stirling, the co-founder of Arbikie, further argues that since the 1970s, the gradual direction of agriculture has led to dominant barley varieties that are more about yield and less about flavor. The use of grains, rye especially, will help to correct this imbalance once again in favor of why Scotch is drunk in the first place.

Scotland is no stranger to both malted and unmalted rye; production records of “Scotch rye” date to 1784 and run through to the Victorian era. A Royal Commission into the definition of “Scotch whisky” conducted in 1908-09 found that rye was widely used in the patent stills of many distilleries at that time. Rye simply fell out of favor in Scotland during the early 20th century (much as it did in the United States) because rye wasn’t a major crop and Scotland found itself developing a dependable international market through its increasingly strong association with malted and blended whiskies. That brought the focus of attention to the warehouse and on cask maturation and finishing, which not all Scotch makers are fond of.

Some 115 years on from that Royal Commission study, definitions raise their head again. InchDairnie’s RyeLaw is matured in new oak casts and contains a minimum 51% rye content to meet the U.S. legal definition of a rye whiskey. But the Scottish regulations are fuzzier.

“We call what we make a ‘rye Scotch whisky,’ but we’re not really allowed to say that,” Palmer says. He and others argue that the regulatory body behind Scotch whisky is overly protective, even if sales of any rye-based product out of Scotland are never going to be a challenge to malts and blends.

“The regulations are a big issue for us,” Palmer concedes. These specify that a Scotch whisky must be distilled from cereals (rye is a cereal) but, specifically, that production also requires distillation from water or malted barley, to which other whole cereal grains can be added. “They effectively say that what we make isn’t a malt and isn’t a blend, so must be a ‘single grain Scotch whisky’ [usually signifying a whisky made from a mixture of malted barley with corn or wheat],” he adds. “But it’s not that at all and certainly tastes very different. That means we’re in a sin bin of whisky categories, categories that are meant to inform the consumer but which, in this instance, will only confuse them.”

Arbikie Distilling has recently joined the Scotch Whisky Association — Scotch’s regulatory body and defender of the UK Scotch Whisky Regulations (2009) — hoping to effect change from within. “I’m not sure how long we’ll stay a member,” Stirling chuckles. “We’re pushing for change and others are pushing too. How long that change will take I’m not sure.”

Why does it matter? Because, he argues, Scotch whisky needs to attract a younger and more diverse audience, and rye is one way of generating interest. That, he suggests, will likely bifurcate the market between the progressives and that “element of the traditional Scotch-drinking market who will just say there’s no such thing as a rye Scotch, those who likely will never come round to the idea. But [the Scotch whisky industry] can’t keep doing the same old stuff year after year. It can’t keep just appealing to that image of the old guy sitting on his couch sipping his whisky.”

While small distilleries are driving the idea of a Scottish rye whisky, the big players in Scotch whisky are dabbling in rye and rye whiskey processes. Chivas Regal Extra 13 is finished in American rye casks; William Grant & Sons has a single grain Scotch whisky that’s heavy on the rye in the mash bill (the grain combination used when making a multi-grain spirit); and Diageo’s Johnnie Walker offers a High Rye blend.

Rye may still be a marginal product — it represents just 5% of the U.S. whiskey market by value — but it has a certain cool. And, maybe through the work of the Scots, a new cachet, too.

“What we and others in Scotland are making is very different from American rye whiskey,” Stirling says. “This isn’t about replicating what’s already available. How do I describe the difference? Well, it’s arrogant isn’t it, but I’d just say that it’s better.”

Join America's Fastest Growing Spirits Newsletter THE SPILL. Unlock all the reviews, recipes and revelry — and get 15% off award-winning La Tierra de Acre Mezcal.