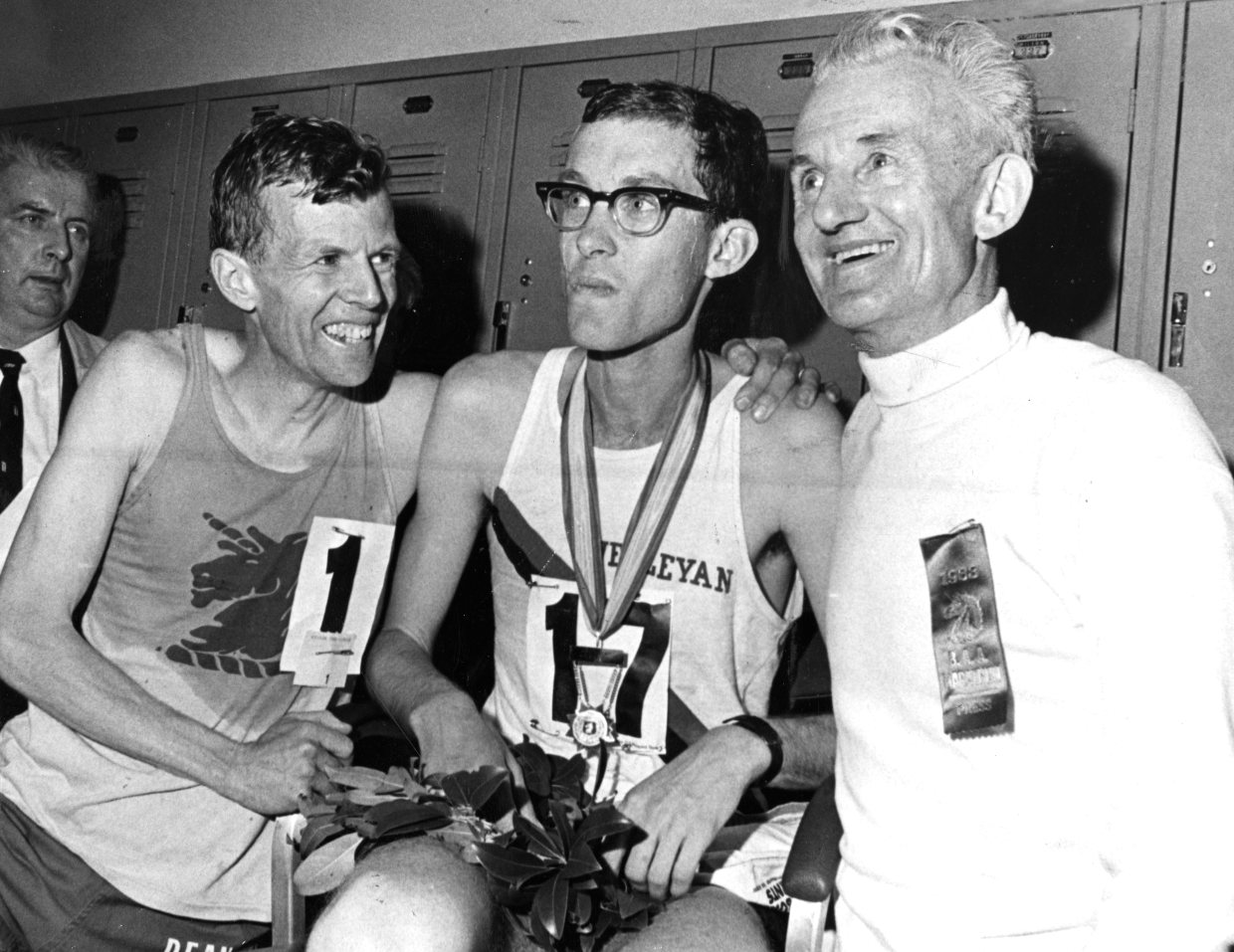

It’s somewhat surprising to see Amby Burfoot — the former Boston Marathon champion and longtime running journalist — wearily reference “complex gibberish” like “VO2 max, lactate threshold and cruise intervals” in a 2001 article for Runner’s World.

Two decades ago, before smartphones and even smarter wearables, some members of the running community were already sick of their sport’s biometric revolution. They were craving a simpler way to measure and predict performance. Which was the point of Burfoot’s post.

He was deliriously excited to share the details on a new workout, relayed to him by his fellow RW correspondent, Bart Yasso. It was simple, and that was what made it so perfect: go to a track and run the 800-meter at a pace that you can manage for 10 repeats. If that pace is 3:30, you should also take three minutes and thirty seconds of rest before your next rep. There was no mandate to change the distance, mix in roadwork, or finish faster. Just cling to your chosen clip for dear life.

That the recommendation for such a workout came from Yasso, a member of the Running USA Hall of Champions, and one of just a handful of people to complete long-distance races on all seven continents (believe it or not, there is a marathon on Antarctica), would’ve lent it more than enough credibility. An afternoon of just 800s? What a welcome reprieve from all those algebraic-looking, multi-distance ladder workouts (e.g. 5 X 400M/MILE + 5 X 300M/1200M + 5 X 200).

But there was a special hook to Yasso’s brainchild, which he told Burfoot he’d been doing for 15 years. It could be used to project one’s marathon time, which, in his eyes, made it an indispensable tool for marathon preparation. He told Burfoot: “If I can get my 800s down to 2 minutes 50 seconds, I’m in 2:50 marathon shape. If I can get down to 2:40, I can run a 2:40 marathon. I’m shooting for a 2:37 marathon right now, so I’m running my 800s in 2:37.”

This detail brought Burfoot to rapture. He wrote, “I talked to about 100 runners of widely differing abilities (from a 2:09 marathoner to several well over 4 hours), and darn if the Yasso 800s didn’t hold up all the way down the line.”

Runners are a dubious, self-referential bunch, though, and considering that over a million train for marathons each year, it wasn’t long before some took to message boards like LetsRun.com to claim that the predictive element of Yasso’s workout was a myth. As one account wrote back in 2005, “[It’s] bunk, for most of us. Maybe if you are a 2:10-2:15 type, or a 4:00-plus type, but otherwise it just does not seem to correspond.”

Critics have mainly taken issue with the fact that the workout registers too prominently as a test of speed, which…would seem an unnatural fit for projecting how someone might perform over 26.2 miles. Put simply: Yasso 800s accommodate a massive amount of rest, which might make it easier for fleet-footed runners to hit fast times and almost fully recover over the course of a long, luxurious jog around the track.

This has proven true on multiple occasions for Ryan Phillips, a former Division 1 runner at Davidson College, who sampled the Yasso 800s while training for both the Chicago and Boston Marathons. Ahead of Chicago, Phillips averaged 2:26 in his 800-meter repeats. He ran 2:36:17. And ahead of Boston, he averaged 2:23 in the workout, before running a 2:30:35. Close? Definitely. But not quite.

“I was very entertained by the numerology aspect of it,” he says, explaining why he tried the workout in the first place. “It ended up being a good order-of-magnitude estimate, but it wasn’t overtly precise for me…I do think it tests both speed and endurance to some extent, but probably the first a little more than the second.”

Despite being “invented” 20 years ago (or 35 years ago, if you count all the years Yasso ran the workout on his own), Yasso 800s still appear as a newfangled training idea for many runners. Even for extremely talented and in-the-know competitors — like Phillips, or his friend Ryan Kuch, whom he calls “probably the fastest amateur 5K runner in New York right now.” According to Phillips, “I heard about it from a couple Davidson guys who now do marathons and ultras. And Kuch had no clue what it was when I told him.”

The workout — and the debate surrounding it — has persisted on this word-of-mouth cache. It has some SEO juice, too. Many trainees, like Evan Nichols, who ran the New York Marathon last year, stumble upon it when preparing for the big race. He saw it on a friend’s Strava page, then googled the workout; there were a number of articles to choose from. Nichols ended up running repeats at a 3:15 pace last fall, in the weeks leading up to a 3:18:18 performance on the first Sunday of November. He remembers the workout as “surprisingly accurate,” yet cautions, “I only did this workout once during training, among a bunch of other track and tempo workouts.”

For some runners, accomplishing the workout at a specific pace conveys the confidence they need to run to that pace on race day. Leslie Shull credits the Yasso 800s with her 3:44:45 finish at the Long Beach Marathon, which helped her qualify for Boston in her age group. “It’s been a long time since I thought about this,” she says. “I absolutely credit Yasso 800s with my time at Long Beach.”I ran with the 3:45 group knowing they would get me across the line. The group leader fell off and it took me a little bit to realize we were off the target! But I was able to pick it up and finish just under the nose.”

Between the clever, “video game” nature of the workout, and the mere fact that marathon training is an emotionally-draining enterprise, and having some sort of idea of what will happen once it’s actually happening is an attractive concept, Yasso 800s will probably never go away. Besides: the eerily accurate anecdotals, when they arrive, give it some staying power, too. As another account wrote online: “I guess we wouldn’t be having this conversation years after the test was proposed if it didn’t have at least SOME predictive value…”

Still, according to Steven Schiff, one of the original members of Brooklyn Track Club, and an experienced marathoner since 2010, “It’s tough to take them seriously as an accurate predictor of marathon time.” While some might see the workout as boosting, Schiff is wary that putting too much stock in Yasso 800s could actually hamper your expectations or performance. “I wouldn’t want to take them that way too literally, because I feel like that’s limiting. Like, maybe I can run my marathon faster than that, you know? I also don’t like to be too pace-obsessive while I’m running my long runs or marathon races, because there are so many things that can arise on race day that you need to be able to adapt to. So in that sense I’d rather run by feel. But it’s definitely an intriguing question.”

Meanwhile, Alan Ladd, a running coach based outside of Belfast, points out that a runner could conceivably log a spectacular Yasso 800s workout, without fine-tuning all the other intangibles that are necessary to run the corresponding marathon time. “The session says nothing about a runner’s endurance, fueling or pacing of a marathon, which are all vitally important. If you haven’t done the miles in training or, say, you make mistakes with pacing or nutrition, the Yasso predictor is essentially useless.”

So who is most likely to receive an “accurate” prediction time from the Yasso 800s? A speedster? An endurance freak? A combo runner? Well, running experts like Greg McMillan ultimately caution that endurance-minded runners (the metronomic, Energizer-bunny types, who tend to hit the same splits over and over again — even if those splits, amongst the gen pop of marathoners, are considered “slow,” ) are likely the only ones who could conceivably expect an accurate mark from a Yasso session. Most “speed-focused” runners will find their 800 repeats well ahead of their marathon mark.

(There’s one demographic, the elite upper crust of marathoners, that may actually defy this formula; long-distance phenoms who finish their marathons around the two-hour mark likely wouldn’t train to nearly break two-minutes in the 800 meter 10 times in a practice. That is preposterously fast, unnecessary and could lead to injury.)

It’s ironic, considering Burfoot first broadcasted this workout for its low-stakes clarity, that it’s ushered in 20 years of confusion and investigation. In that original post, he wrote: “Training doesn’t get any simpler than this, not on this planet or anywhere else in the solar system.”

But the workout, sans its marathon baggage, is a simple workout. And it’s an effective one. I would know; I’ve tried it twice this year, each time targeting (and hitting) 3:00 over 10 800-meter repeats. There’s a lot to like about Yasso 800s, as track sessions go. I appreciated the length of it — five miles on the track, plus another two-and-a-half miles of jogging. I appreciated that I could feel my body getting better at pacing as it went on. I was hitting 90-second laps without even checking my watch by the fourth 800. And I appreciated the fact that it starts relatively easy (it’s not like doing 200-meter repeats, where your hamstrings are in shock for the first few repetitions), but ends really, really hard. The last few took me to a dark place, which meant I was getting better.

I have never run a marathon, and am not currently training for one. Does this workout mean I could go out and run right around 3:00:00? Maybe. Who knows? I would also need to work up to 20 miles on the roads, run a half or two to get a feel for that sort of pacing/racing, and learn more about what my body needs to compete over that many miles in a given day. At the moment, I don’t have an answer.

There are other, better predictors of your marathon time out there. Google around, and you’ll find all manner of experts encouraging you to run 10Ks, multiply by two, add X, etc. But isn’t that the sort of over-analytical gibberish that we’re all trying to avoid? It’s possible that Yasso 800s represent a cutoff of sorts (e.g. if you can’t average 3:00 in the workout, you can’t expect to break 3:00 on race day), but how does that relate to what week of training you logged the session? Or any minute improvements in your mindset? Or the possibility that you run well with cooler weather, or actually prefer covering terrain to running loops around a track?

In the end, the best way to know what you might run in a marathon is to just run a marathon. From there, if you’re so inclined (and there must be something in a marathon’s water cups, because so many runners are), you have a predictor for the next one. For those not training for one, this doesn’t mean Yasso 800s aren’t worth your time. In fact, they’re a rather simple and accurate predictor of something else: your mettle.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.