Not long after hopping on a Zoom call with personal trainers Hector Guadalupe and Tommy Morris a couple weeks ago, I asked if I’d be needing my yoga mat. I was calling from my apartment in Bed-Stuy, where I’d cleared a sizable-enough rectangle of space in the room that triples as my kitchen, dining room and living room. Guadalupe laughed, saying it was entirely up to me. He and Morris didn’t need an assist from any fancy equipment — mats included — to whip me into shape. After all, they could cobble together a grueling workout in a six-by-nine-foot concrete cell. It wouldn’t be the first time.

Guadalupe is the 42-year-old founder of A Second U Foundation, a New York-based nonprofit dedicated to helping former inmates get certified as personal trainers and connecting them with jobs and clientele in the industry. In a country with historically harrowing recidivism rates — 56.7% reoffend within a year of coming home, while a 2018 national study showed 83% of prisoners are arrested again in the nine years after their release — A Second U is an example of what can happen when we give those with convictions, well, a second chance.

Over three years, not a single man or woman who has gone through Second U training has reoffended. Of the near-200 graduates Guadulupe’s program has produced, 93% of them are currently employed and working in jobs that pay at least $35 an hour. But there are intangibles at play, too, something about the positivity and community inherent to fitness, which propelled Guadalupe during his own time behind bars.

Guadalupe grew up on Flushing and Broadway, in “old Williamsburg, borderline Bed-Stuy,” as he calls it. He acknowledges that those blocks are yet to get as fancy as the “other side,” the Williamsburg-Greenpoint region now marketed as North Brooklyn, where average rent has gone up 80% since 1990, making it the fourth-most expensive sub-market in New York City (behind only Downtown Manhattan, the Upper West Side and Midtown Manhattan). The streets of his youth, though — just a few minutes from where I live — don’t need an Apple Store or Sweetgreen to prove their point. For Guadalupe, they’re already unrecognizable.

“The New York that you see never really existed. It’s our current reality, but it’s not really my memories,” Guadalupe says. “I was born in ‘78. I grew up in the ’80s and ’90s. It was a very hectic time. From Wall Street to my hood, everything was corrupt, everybody was getting high, there was a lot of death. Law enforcement never protected anyone. It was a very sad city, which over the past 20 years eventually became a great place to be.”

The 42-year-old trainer compares growing up poor to being born with a blindfold on, or living your life in a wheelchair, unable to join in with all those you see running right on by, those who make it look so easy. At an age when most kids were asleep before 10 p.m., fretting about pop quizzes and long division, Guadalupe would find himself on Dekalb Avenue at three in the morning, searching for a payphone so he could find a relative to pick him up for the night. His mom, a victim of the crack epidemic, would sometimes forget about him for days at a time. His house was full of “zombies” during that period. Guadalupe feels lucky he was never abducted or killed.

He stresses that the era’s various subversive campaigns against the poor, like the boots-on-the-ground enforcement of Reagan’s War on Drugs, worked to destroy his already desperate neighborhood while misleading the public about what was really going on. “When people are on drugs, they’re not bad people. They’re sick people. There’s a difference. But they said fuck it, we’ll increase the prison population,” Guadalupe says.

“This is what I grew up in. You didn’t see dudes becoming doctors. What you saw everyday was people trying to survive. The narcotics trade was the biggest form of survival. The NYPD was your rival. The NYPD sold guns. They sold massive amounts of dope. They were kidnapping people for ransom. In the Stuy, in the ‘80s, the FBI came into the neighborhood and locked up half the police station. This was my reality.”

That reality boiled down to three imperatives: stay alive, don’t get shot and don’t go to prison. All three became exponentially more difficult after Guadalupe started spending time with guys who were making up to $100,000 a day. At 16, Guadalupe was “moving.” By the age of 23, he was running his own enterprise, pushing narcotics from from Cape Cod all the way down to Miami. Crossing state lines is another animal, with way more risk — and that was when the FBI started forming their case. Guadalupe was sentenced to 10 year to life, and spent a decade in federal prison, shackled and shipped from one hellhole to another, from California to Arizona to New Jersey to Ohio.

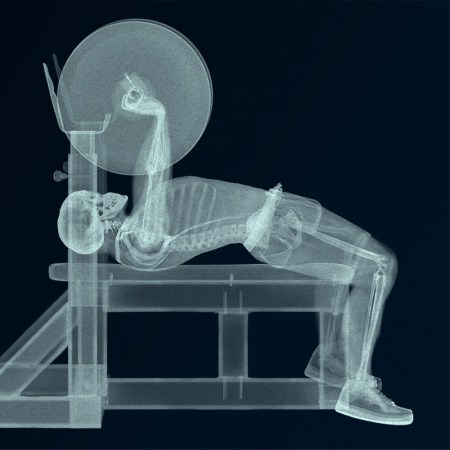

Like many inmates before him, Guadalupe began working out in prison in order to hold his own in a notoriously violent environment. As he explains, “There were a ton of wars in there. It was international. You’ve got the Sureños Mexican Mafia in there. Italian mob. Russian mafia. Different states represented, like 200 guys from DC or 400 guys from New York. It was super political. You gotta be in really good shape, you gotta work out like a monster and be as sharp as you can, mentally.”

But he stuck with his fitness journey — became “obsessed” with it, even — after realizing how good it made him feel. The entire purpose of the process shifted, from self-defense to self-worth. Along with reading and meditation, exercise carried him through his worst days on the inside, which included months of solitary confinement. And it even meshed well with those hustling instincts that had landed him in prison in the first place. While at New Jersey’s 5,000-strong FCI Fort Dix, Guadalupe used his operational knowledge (bookkeeping, accounting, management, sales) to launch an off-book training business.

Leveraging his position at the prison gym, he started brokering access to equipment. He would sell a bench, a bar and plates on a specific day at a specific time. One-on-one training cost a bit more. Wives on the outside wired money to his people, and fully committed trainees were paying him up to $1,000 a month. He stopped caring about color or gang affiliation or even hierarchy. Guadalupe even trained correctional officers. “I was like, you walk around here like a bag of shit. Let me teach you how to exercise, let me teach you how to eat.” To prepare for his eventual release, Guadalupe trained for certification courses, and started getting excited about life as a fitness instructor in the city he would one way day go home to.

Despite his nonviolent offense — and his extensive experience running a gym — it took almost a year before anyone in New York took a chance on him. Eventually, a health club downtown did. Guadalupe didn’t take a single day off for four years. Not even Christmas. He built up a clientele of white-collar trainees who work for companies you’ve definitely heard of. It occurred to him that that kind of acceptance, that kind of network and (especially) that kind of hourly cash flow, is the ultimate tool in the fight against recidivism. There had to be something beyond halfway houses, beyond nonprofits doing their best. And thus, four years ago, the A Second U Foundation was born.

Tommy Morris, the other trainer who joined Guadalupe and I for the virtual training session, says he’s keen on fixing “imbalances.” In prison, while fighting for the boxing team, he’d perform up to 1,000 push-ups a day. It got him shredded, but it also shredded his shoulders. He’s wary of aimless, high-rep bodyweight circuits, and prefers to focus on understated, precise movements performed slowly and deliberately. In case that sounds leisurely — it’s most definitely not. Morris had me performing push-ups into downward-facing dog, then lunges with hip twists, then bicycle crunches. There was no rush to finish. For Morris, there are only movements and the right way to do them. If that means a set takes a little longer to finish, so be it. I was howling by the end of our workout.

“When we think of injuries, we think of a snap,” Morris says. “But most of the time that’s not what it is. It’s the minor wear-and-tear, which years later, all of a sudden, you’re feeling something horrendous and you’re not sure where it came from.”

Morris’s training philosophy borrows from strength training, functional fitness and yoga. It’s born from a mentality where fitness is not a destination — forget that “wedding weight” or your ideal “beach bod” — but one of life’s most important pursuits. Injury prevention, it turns out, can still get you into pretty good shape. He had 27 years to reach this level of understanding, after serving time for two homicide convictions. These days Morris lives with his girlfriend in Crown Heights. He has a dog who barked intermittently throughout our session. He’s saving up to buy a house in Florida. And with only 40 minutes and a screen to work with, he gave me my hardest (and best) workout of the entire year.

Like so many others, Morris is a graduate of Guadalupe’s program. With his violent offenses, he has next to no shot of getting hired at a corporate health club. But after graduating from A Second U’s six-week program (which 10 individuals attend a quarter, covering interview prep and Microsoft skills, in addition to fitness and training), Morris was given a position at Guadalupe’s organization. Guadalupe texted me later in the day, writing “He’s one of my favorite graduates. My entire team are the sickest coaches in the country.”

The survival instincts that kept these men alive on the streets and behind bars translate well to a life devoted to fitness. There is grit here, and drive, but also patience and knowledge. The barometer for whether a workout “worked” isn’t in knowing the detailed, decades-old regrets of the man training you, but in the heaving of your lungs, the sweat on your brow, the burst of endorphins when you perform a lunge correctly, and actually keep your knee from sliding past your toes. These trainers are well-equipped for a world where kitchens and living rooms must double as gyms not just because they’re used to confined, makeshift spaces, but because they’re damn good trainers.

A long list of New Yorkers certainly seem to think so. A Second U Foundation has a wide array of clients, from Bradley Tusk, a venture capitalist and former aide to Mike Bloomberg, to Samantha Majic, a political science professor at City University’s John Jay. The foundation regularly works out the entire staffs of brands like Faherty and Bombas, which pay for their employees ($35 a head, per hour) to exercise as a team over Zoom. Individuals, meanwhile, can book a fitness evaluation with a trainer from A Second U, and set up individual sessions, which come in at $45 an hour. All told, it’s more than Guadalupe could have imagined when he first came home. And that’s exactly the point.

“It’s a community,” he says. “We’ve got almost 200 trainers, almost 1,000 supporters and corporations. That’s a family. That’s a big-ass family.”

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.