Something astonishing happened at the 1980 Houston Marathon.

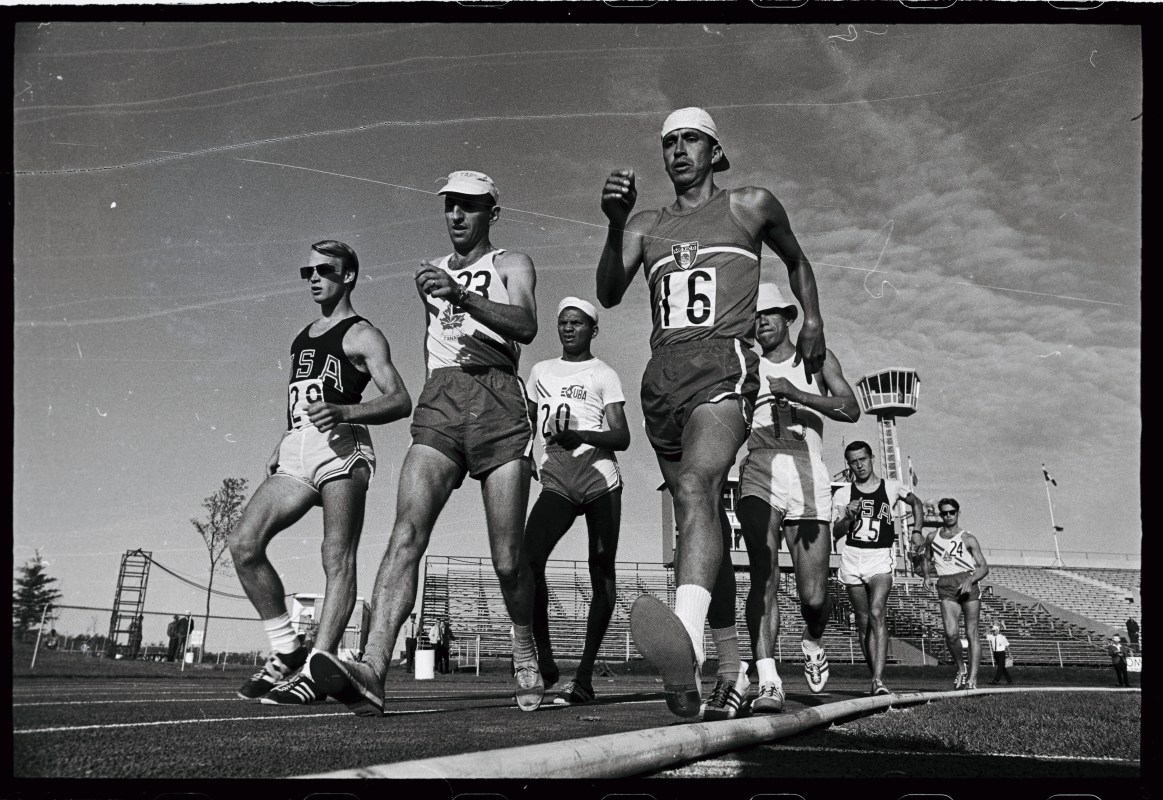

A one-time Olympian named Jeff Galloway — who’d run cross country at Wesleyan with running royalty like Amby Burfoot and Bill Rodgers — finished in third place with a scorching time of 2:16:36. (That’s about a 5:15 mile pace.) But that wasn’t the amazing part; as impressive as breaking 2:20:00 over 26.2 is, runners have posted similar times in thousands of races over the decades.

What you usually don’t see in a race of that length or magnitude is the bronze medalist taking frequent and schematic breaks…in order to walk. It’s true: every two miles, Galloway walked for up to 20 seconds. Then he got back to it. The game-plan clearly didn’t hold him back: he beat the fourth-place finisher by over a minute, and the final time was his personal fastest ever for the distance.

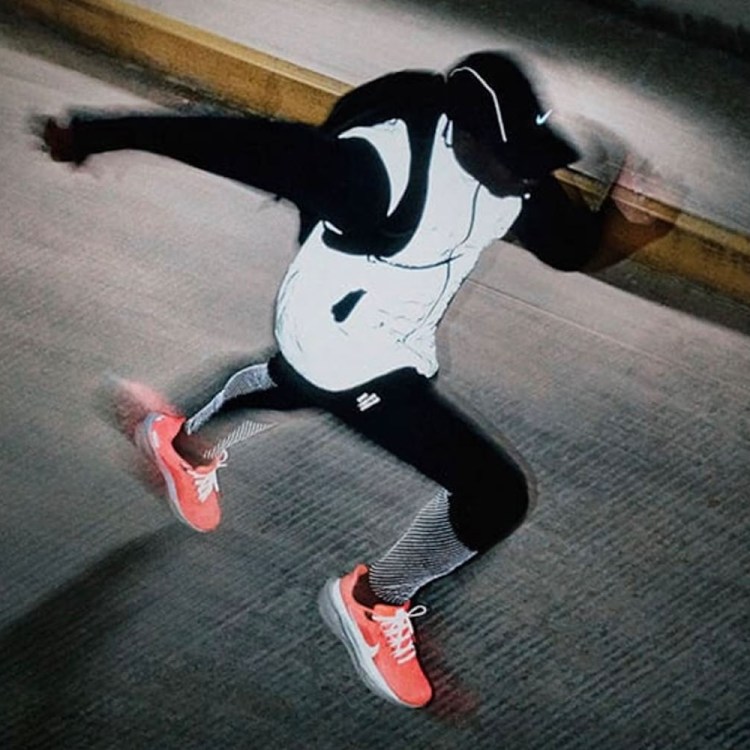

For so many runners, the idea of walking during a run is unthinkable, let alone a race. The activity is absolutist in its definition (“an aerial phase in which all feet are above the ground”) and feels non-negotiable in practice. To walk is to admit some sort of moment-to-moment defeat — to let the stitch in your side or the uncertainty in your mind win. Walking is weakness.

Or, maybe…maybe it’s strategy? A form of auto-regulation. The best shot you have to keep running: around your block, at the Houston Marathon, over the long arc of your life. We recently spoke with a variety of runners who swear by the unheralded run-walk-run method, for a variety of individual reasons. Our clearest takeaway? The practice is far more common — and way effective — than you’d think.

How to Prevent the Most Common Running Injuries

There are six of them. We explain how to train against each.Intro to Run-Walk-Run

So, Galloway wasn’t just struck with a bizarre, single-use urge to walk that race in Texas over 40 years ago. A few years prior, he’d started tinkering with his training, in a quest to develop an injury-free program; along the way, walking made an unlikely leap from sacrilegious to sacred.

Ever since, he’s built an entire movement (and brand) around the idea of interspersing your run efforts with periods of walking. Run-walk-run is a family affair, too: his son (Westin Galloway) followed in his father’s footsteps, literally, and broke the vaunted three-hour marathon barrier using walking intervals.

The Galloways have an app and a pacing calculator online, and legions of supporters, including longevity guru Jesse Itzler, who’s used the strategy for 20 years. “Benefits include delayed fatigue, conservation of resources, quicker recovery, mentally breaks down the race into digestible bites, [and] less stress on ‘weak’ links,” he reported in a recent Instagram post. Itzler runs ultra distances (he’s the founder of the Runningman Festival) and follows a more stretched-out run-walk cadence: seven minutes running, three minutes walking, repeat.

Why Runners Walk

Run-walkers don’t necessarily owe you an explanation, but they do have them. Injury prevention is the most prevalent. Adrian Todd, a hiking coach and trail runner, says the first time he plugged walking intervals into his runs he was returning from a stress fracture in his foot. “I used them to get back into longer easy runs,” he says. “They’re great for easing back in after a long layoff, and especially useful for active recovery between tempo/threshold pace intervals.”

Ashley Castleberry’s had a similar experience. A NASM-certified trainer, she started incorporating 60-second walking breaks into her runs five years ago. “I was skeptical at first,” she says, “but [the breaks] dramatically improved my endurance. Walking gives my muscles a chance to briefly recover, which reduces fatigue and risk of strains or pulls.”

Over the years, Castleberry has settled into a bespoke regimen. For quick morning runs: run four minutes, walk one minute. For long weekend efforts: walk two minutes for every six miles run. If that sounds random, well, run-walk-run rhythms generally are — they’re the byproduct of years of optimization.

There’s scientific evidence that this strategy doesn’t hurt race times, but many run-walkers aren’t thinking about competition at all. For Ryan Godwin, an aging runner and food tech consultant based in Denver, run-walks simply come with the seasons. “There’s least a chunk of the year where outdoor running is less attractive,” he says. “This means that there is generally a period of time each spring where I need to readjust to running outdoors. That’s when I incorporate walking the most.”

Run-walking is as global as the sport itself. We connected with a Melbourne-based marketing specialist who finds that a guaranteed walk every five-10 minutes helps him set “achievable goals”; a Swedish marathoner who stops to take pictures of sunrises and sunsets on her runs; and even a freshly 50 web designer from London who’s willing to do whatever it takes to jumpstart a sustainable running habit…including walking. (He’s dating again and wants to get fitter.)

Isn’t It…Embarassing?

There’s a not-so-secret reason that many runners — even casual ones — don’t want to walk on runs, or in races: pride. It feels embarrassing. The idea of stopping to walk (strategy or science be damned) is almost painful to consider. But know that every run-walker had to grapple with this very mental conundrum at the outset of their journey. “Most runners are afraid to walk,” Todd says. “I understand that. I was one of those runners. But it’s important to recognize that walking can be an excellent tool.”

Castleberry, who has run half-marathons and marathons, takes it a step further — “It requires some mental fortitude to take walk breaks during a race.” Letting others pass you at the four-mile mark (even when you’re feeling good) isn’t craven. It’s brave. It’s the ultimate epitome of “running” your own race. Itzler said it the bluntest in his Instagram post: “I couldn’t care less what people think…all I care about is finishing.”

There isn’t a single runner who’s too big-time to walk for a bit. But the running community’s scattershot embrace of walking is typical and sort of mimics runners’ collective difficulty to slow down their long runs, or stick to Zone 2 in training.

Anthony Middleton, an adventure runner who’s completed Morocco’s iconic Marathon des Sables (six marathons in succession in the Sahara), says that after he hit a plateau in his times, he finally gave in to the fact that his training was ego-based. “Going for a personal record on every run is the physical ramblings of a madman,” he says. (This hits especially hard, considering he is the running equivalent of a madman.)

“I was in training mode for a 100 mile-plus ultramarathon in Thailand when I decided to (a) run slower without a time in mind, and (b) implement walking distances during my runs. The race I was training for was by far the longest I had attempted in one run and my motivation to incorporate the walk-run method was to make sure I could complete the intimidating distance in blistering, tropical heat. Both strategies helped me immensely. I successfully finished this mammoth task. To this day, I still include sessions when I walk during runs.”

Strategies to Try

What should your run-walk routine look like? That’s for you to figure out. Middleton says it’s important to have fun with it. Get out there and experiment; the whole point of incorporating walking intervals is to take back control, make running a little less daunting and (over time) maybe help yourself go that little bit further.

To that end, think of this run-walk ratio, courtesy of Coach Chris Knighton (a marathon instructor from Providence, Rhode Island), as a suggestion, not a prescription. It’s a training concept you get to try out, to see if there might be a fit:

- Run one miles, walk one minute

- Run three miles, walk three minutes

- Run five miles, walk five minutes

Coach Knighton says those three cadences tend to produce the best results — and that his athletes specifically see the most progress when they stick to a particular formula. Give ’em all a go. Notice that despite that 1:1 miles-to-minutes consistency here, each offers a very different sort of strategy for eating up mileage. Another method to consider? Set out to complete a distinct number of miles, and commit to walking the final three or so. (This will work wonders for your cardio recovery, forcing your heart to ease into a steady state after the effort.)

Ultimately, running is far more than its rigid definition. It’s less about the fact that you never stopped, and all about the fact that you kept going. Whatever it took, however “slow” it felt, however much you worried about how it looked, you hung in there. You adjusted, you gathered yourself, you started in one place and ended up somewhere else. That’s running.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.