It’s a dream for many parents: to know the full spectrum of developmental possibilities for your child (or as much as can be gleaned from their DNA, anyway).

Razib Khan made headlines in 2014 after his son’s genome was sequence fully when he was still in utero, making Khan’s child the first born with its entire genetic makeup fully unraveled. The geneticist, who decoded his unborn child’s DNA essentially out of curiosity, told Technology Review his own method “was more cool than practical.”

Unlike most prenatal tests, genome sequencing unveils the information stored in the entire strand of DNA (as opposed to one gene that’s targeted for its connection to a specific disease). A test for 3,000 diseases sounds like an incredible scientific advancement, but many doctors find the notion of such comprehensive testing to be troubling.

Writing for Technology Review, Antonio Regaldo observes:

“… [The] discovery of a bad mutation could lead parents to an ‘irrevocable action’ such as an abortion, says [Executive Director of the Mother Infant Research Institute at Tufts University Diana] Bianchi. Yet DNA isn’t always destiny—sometimes a person has a genetic defect but no symptoms.”

Essentially, medical professionals are worried the tech will be applied too liberally and give parents a false sense of knowing the future. Some are also worried such testing would snowball into “designer babies,” with genetically-modified children manifesting from the false confidence imbued by the fully-decoded genome.

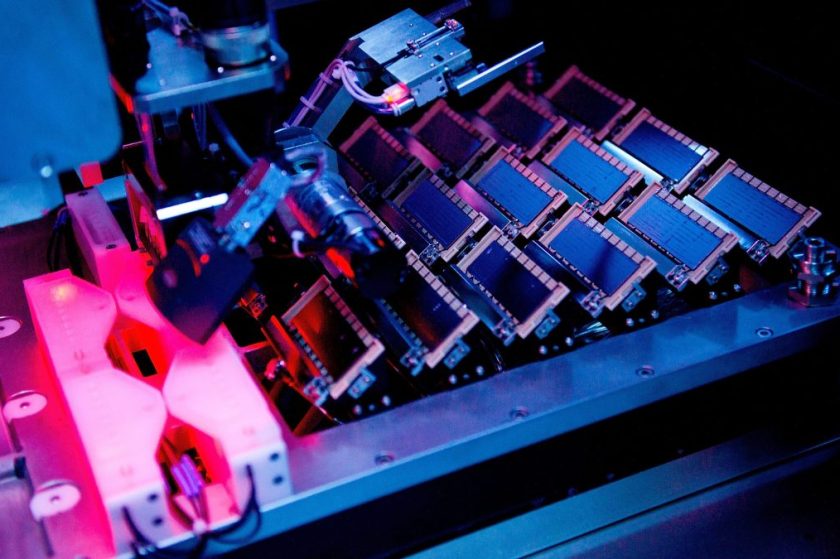

Since the article on Khan’s work was published in 2014, the field of genomic sequencing has made leaps and bounds as its testing equipment has advanced. At Baylor University, researchers say they are close to developing blood tests that can sequence a fetus’ genome. That means parents won’t need invasive testing (or, like Khan, a degree in genetics) to ascertain their child’s fully-decoded DNA. It’s worth considering the question: Will giving parents access to this information, which feels definitive but in fact can be misleading, really a step that should be taken?

To learn more on the advent of genomic blood testing, read the article here. To revisit the ethical implications of prenatal sequencing, click here. To learn more information on “designer babies” and the fears tied to genetically-modified-organisms, watch the video below.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.