Travel jetlag can sometimes be kind of nice.

Earlier this summer, coming home after a couple weeks spent six hours ahead in the Mediterranean , I suddenly had superpowers. I was doing full track workouts at six in the morning, buying the newspaper from a shop down the street, waving to neighbors like I was in a Hall & Oates video montage. You know: typical and infuriating morning person behavior, of the sort that other folks are up to while I’m usually rounding out the plot of my final REM cycle.

That’s part of the transaction we make when we fling ourselves across the world, violently destabilizing our careful wake-cycles in the process. For all the fun I had posing as an early bird (it lasted all of five days), anyone I might’ve annoyed with my act would’ve been gratified to have seen me that first day in Italy, awake for 30 hours straight, my eyes twitching, making batshit decisions — I think I paid a smirking gondolier 80 euros — as I stumbled in search of espresso.

We take the wins we can get from travel jetlag, while powering through the worst of it, because we don’t have much other choice. That’s how travel works. Disturbed sleep, persistent fatigue, an upset stomach, nuclear moodiness…for most people, it’s all worth it to, say, climb the steps of the Duomo.

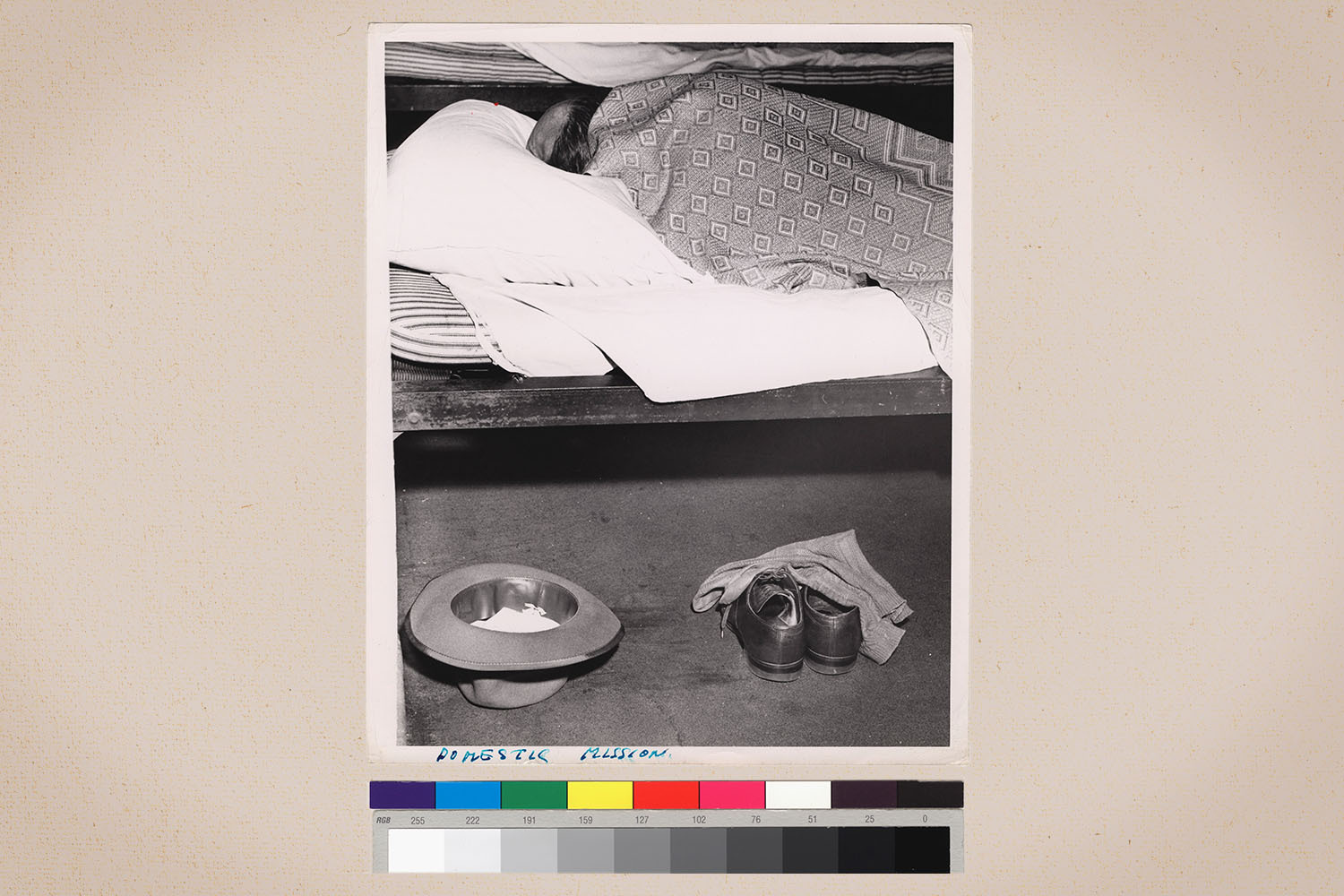

But there’s another form of jetlag that we regularly accept — on a more consistent basis and with less obvious pay-off — that rarely gets the sort of attention we pay the “travel” kind. That would be social jetlag, a term that was coined 15 years ago by a team of German researchers. Among their many working definitions, they submitted: “Social jetlag represents the discrepancy between circadian and social clocks, which is measured as the difference in hours in midpoint of sleep between work days and free days.”

What does that mean? Basically, inconsistencies in your sleeping pattern lead to an accumulation of sleep debt, which can lead to fatigue-filled days, similar to my zombie afternoon in Italy. But while that physiological performance might seem novel and humorous when it’s a a one-off on a different continent, it isn’t so charming when you have emails to send on a dreary weekday morning. The primary way we “pay back” this debt is by sleeping more — which often means sleeping in.

What does social jetlag really look like?

There’s an obvious example for all of this. Imagine that you’re a normal 9am-5pm employee with a customary 11pm-7am sleep cycle. Then Friday rolls around and your friend’s in town. They want to do dinner and drinks. Your normal sleep-wake cycle has you scheduled for a wind-down routine around 10pm — lights low, hot shower, sleep tea, the works. Not on this particular night. You stay up listening to music, sharing appetizers and buying rounds. Your head doesn’t hit the pillow until 2am. Heading into Saturday morning, the whole wake-up process has been pushed back. You either rise at your normal time (and elect to operate with three fewer hours of rest and recovery than you’re used to), or make the executive decision to stay in bed and see what sleep you can scrounge together.

Unfortunately, neither is much of a solution. In the short-term, your next few days will be reactive to the night of irregular rest: you’ll have to shake off something called “sleep inertia” (defined as “a period of impaired performance and grogginess experienced after waking”), which tends to make exercise pointless, cognitive tasks difficult and operating a motor vehicle dangerous. You’ll probably then eat some crap throughout the day, as we’re wired to consume foods high in calories, fat, sugar and salt when we’re really dragging. And the following night, when you get a another crack at sleep, you might purposely overload on hours, in an effort to erase the misery and “reset.”

But what about the night after that? And particularly if it’s a Sunday night, with meetings or appointments in the morning that are weighing on your mind? What if you logged too many hours of sleep, in response to the night where you didn’t sleep at all, and now you’re lying in bed, counting full herds of sheep, feeling wide awake, desperate for any sign that you might fall asleep, ruing your damned friend and the many dollars you spent on mozzarella sticks?

Look: a life well-lived includes grabbing meeting friends on Friday nights. Quarantine reinforced that much. But even necessary and innocent disruptions to your routine can have a tangible impact on your body’s ability to get the rest it needs, and your ability to perform the tasks you need to perform. And it’s a little too easy to convince ourselves that we’ll always bounce back from a bout of social jetlag. You beat a night of insomnia, or beat back the fatigue, and by the next Friday, you’re ready to do it all again.

The pernicious cycle doesn’t have to involve alcohol either. Think: high schoolers staying up late to do homework or play video games, young parents taking shifts throughout the night to care for their newborn, sports fans that will stay up (or get up early) when their team travels to a different time zone, older couples who queue up a lengthy movie one night a week after dinner. We all experienced it in personal ways during the pandemic; even without anywhere to “go out,” there’s an inclination at some point in the week to stay up late, make popcorn, open a bottle of wine, whatever.

Social jetlag is also sometimes out of our control; a predilection towards waking up early (“morningness,” early birds) or staying up late (“eveningness,” night owls) contains more genetic determinism than most people realize. Your chronotype is considered the “natural inclination of your body to sleep at a certain time.” It shifts as you age (children have early chronotypes, adolescents have late ones, adults — and especially older adults — have early ones), but it’s still programmed somewhere a 10-hour sleep window relative to your peers. My chronotype, for instance, has always been late. I find it very natural to fall asleep around 1am.

How does this relate to social jetlag? Well, falling asleep at 1am isn’t ideal when you have a science quiz at 7:45am. Or the first shift at a construction site. Or a morning flight to man across the Atlantic Ocean. Most conventional education and employment responsibilities hinge on a sunrise schedule. If you’re yawning through your duties, you could be seen as lazy or ill-prepared (and sometimes, maybe, that’s true). But it could also be a signal that your predetermined “eveningness” is sabotaging your ability to conform to a superstructure designed by and for morning larks. After all, how many tech titans and LinkedIn influencer-types extoll the rise and grind mentality?

It’s a conundrum. There are very few fields that encourage or reward eveningness. (You’re best served becoming a night guard, or…an enigmatic sculptor.) Besides, the body doesn’t distinguish between behavioral decisions and professional commitments. If your sleep is consistently disrupted, your daylight productivity, mood and energy levels will suffer in kind. And this cycle tends to compound on itself — bad sleep begets worse sleep, while creating regrettable lifestyle habits; it probably doesn’t come as much surprise that people who stay up later are also more likely to nosh midnight snacks, abuse drugs and alcohol or binge on screentime. Over the span of a life, those little decisions tally up. Socially-jetlagged adults are more susceptible to heart attack, depression, road rage, you name it. Morning people, meanwhile, literally have a scientifically-proven positive association with “cheerfulness.”

It didn’t escape me that what officially ended my travel jetlag this past summer was my social jetlag. Seriously. There was a battle of the jetlags the first weekend that I was back in the States. After just one week of morning person-ing, I was excited to be back in New York around friends and went out late one evening. (Really, really late.) The adventure shattered whatever temporary adjustments had been made to my sleep-wake cycle. I wasn’t just back on my old schedule; I actually slept in by EST standards the next morning, and now needed to do the usual song and dance of resetting by Monday morning. (Which again, takes some extra effort from me, as someone with a late chronotype and a history of insomnia.)

It’s enough to make anyone feel powerless. What the hell are we supposed to do about social jetlag? Especially if we’re battling it on two fronts? Is it just the price of admission for a dynamic life? Similar to flying across the country once in a while? Well, that depends on your age and your expectations. If you’re living in a city, with zero dependents, discretionary income and an Excel list of restaurants and bars you’re eager to try, maybe you can make your peace with regular circadian misalignment. Different demographics might also be able to justify their tolerance for sleep disruption, to varying degrees.

But as a general rule, good sleep is a good idea. And good sleep is consistent sleep. The best way to ward off social jetlag, and all the nefarious side effects it sows — regardless of your chronotype — is to pick a bedtime and a wake-up time that corresponds to the rigors of your life, then stick to it, come hell or high water. Whenever those special dinners, holiday parties, wedding weekends or big games arrive (a US Open quarterfinal finished at 2:50am this week!) you have to make do with less sleep on the morning end, instead of pushing your wake-up time towards noon. The sheer discomfort of those days, which will likely require copious caffeine and a strategic nap, should be more than enough to keep you from making them a habit. If you do rely on sleep-ins though, you’ll be more inclined to allow them as a regular occurrence, and once they’re a regular occurrence, they’ll have the momentum they need to create a crippling cycle.

What are the best ways to combat social jetlag?

When we start to break down sleep in this way, throwing around all sorts of fancy somnological terms, it’s easy to drift from the functional meat and potatoes of getting a good night’s rest. Which is what any of us really needs to be thinking about. (If you’re headed to bed each night wondering if you’ll get enough hours to ward off dementia decades from now, you’ll eventually never want to wake up.) To that end — the best way to conquer social jetlag is to court best practices. I’ve compiled my favorites below, many of which I’ve learned from listening to Dr. Andrew Huberman, a Professor of Neurobiology at Stanford Medicine and the host of Huberman Lab:

- Get outside within 30 minutes of waking and take in sunlight

- Consider exercising and/or taking a cold shower to jumpstart your day

- Wait 90-120 minutes after waking up to take in caffeine (will help avoid an afternoon crash)

- Cut the caffeine off completely by 2pm

- If you must nap, don’t do it so late in the day (or for so long — more than 90 minutes) that it will hijack that night’s sleep

- Get outside throughout the day, especially when the sun’s at a low solar angle, to inform the brain that the day is ending

- In other words: watch the sunset, which is a lovely habit to get into in general

- Try not to work out too close to bedtime, as it releases stress hormones and elevates heart rate

- Avoid artificial lights of any color within an hour of heading to bed

- Dim lights all over the house, and particularly those on the ceiling (which trick the brain into thinking the sun is still out)

- Observe daily nighttime rituals: hot shower, hot tea, a bit of reading

- And always practice sleep hygiene, which means observing your bedroom as a sanctuary for sleep and not stress

- That means no electronics in the bedroom, if you can manage it

Notice that these tips — all of which I’m currently working to fold into my daily regimen — don’t necessarily favor early chronotypes or late chronotypes. They’re also malleable to most forms of work schedules, and provide a blueprint for tinkering your way away from a “climb into bed and see what happens” sleep-wake cycle, which I’ll admit, I practiced for most of my adult life to very little success.

Think about it: even if you went out 75 days in a given year (a number that may seem tame to some, but will sound about right for most), that’s only 20% of your sleeps. Those other 80% definitely deserve some kind of a plan. And the more you stick to that plan, with a preparatory checklist, and a goal bedtime and wake-up time, the less time you’ll have to spend hoping for the best and dealing with the worst. As annoyingly cheery as I was riding the short high of some travel jetlag gone right, I can assure you, it’s nothing compared to gaining lasting control over social jetlag. Wake up yourself before it’s too late.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.