I was at a bar earlier this summer, waiting for a drink, when I heard a man grumble that there were “No good sports on today.” I surveyed the TVs and quietly agreed with his assessment. There was an inconsequential baseball game on MLB Network, and one of those bizarre-looking Red Bull events, going on in Boston.

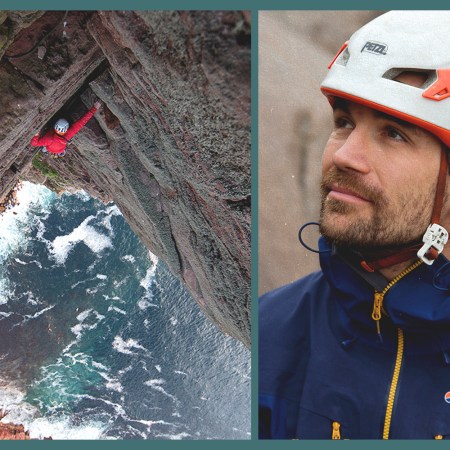

But a half hour later, that man (along with me, and the rest of the bar) was transfixed by the latter. It was the sole North American stop on the Red Bull Cliff Diving World Series, probably the most exciting coterie of touring athletes that few of us know anything about, and for hours, we watched as men and women launched themselves off the roof of the Institute of Contemporary Art into Boston Harbor below.

The league has existed for 13 years on the men’s side, eight years on the women’s, and each season, visits eight locations throughout the world. Red Bull cliff divers have leapt from opera houses, ocean bluffs, a 16th-century Ottoman bridge. The tour has traveled everywhere from a lake in Fort Worth, Texas to a pair of towers in Dubai. For a site to qualify, the platform has to be somewhere in the neighborhood of 27 meters above a body of water. And, in true Red Bull fashion…it needs to be a cool-ass place to fly a drone.

Like traditional diving, of the sort that you might tune in to watch once every fours years in the Olympics, Red Bull cliff diving involves aerial acrobatics, weighted scores and podium finishes. There are currently eight “permanent” athletes competing in the men’s and women’s competitions, plus a rotation of wild cards, who are plugged in at various points throughout the tour. Standard enough. But the intrigue of the fledgling sport lies in its natural environs, which convey beauty, danger and unpredictability, while offering an incredibly unique spectator experience for the host city (or castle, or national park, or Indonesian island…seriously, this tour will go anywhere).

As this year’s installment of the tour heads into its final championship on October 15th, the first-ever at the Sydney Harbor Bridge, I reached out to a pair of ascending cliff divers — Ellie Smart and Molly Carlson — to try and glean a more enlightened understanding of their sport. What sort of shape do you have to be in to fling yourself into a rushing river? What do they worry about up on that platform? Will cliff diving ever make it to the Summer Olympics?

Smart and Carlson talk origin stories (unsurprisingly, they grew up around the pool), the importance of mental toughness, the difference between offseason and in-season training, the perils of learning a new dive and their favorite sites to dive from throughout the planet.

How does one even find out they’re good at this?

Ellie Smart: I did my first dive-in competition when I was five years old, and I just loved it. As I got older, I tried platform diving and I immediately loved the thrill of going from higher up. I dove in college at UC Berkeley, but actually quit diving. There were issues with the team and some things going on that I didn’t agree with, ethically. Hanging up my swimsuit was the hardest decision of my life. That was really difficult. My whole identity was wrapped around diving; my dream was always to go to the Olympics and represent my country. Almost exactly a year later, one of my friends took me cliff jumping. At first I was like “No, I don’t want to go, that’s so dumb,” but I remember jumping off the cliff that day and thought, “What if this is what this was all supposed to be leading up to? What if this is what I was supposed to do the whole time?”’ That exact day, I set a goal that I wanted to be a Red Bull cliff diver. I emailed everyone I could, asking “How do you train? How do you do this?”

I reached out to my now-fiancée — who was a friend/stranger on Instagram at the time — and said “I want to learn how to do this. Like you’re doing it. Can I come along?” So I booked a one-way ticket to England to train for high diving at the Adrenalin Quarry. My goal was to train the whole summer to compete for Red Bull in 2018, but I learned all my dives within three weeks of moving. I was invited to the first competition of the 2017 season in Inis Mor, Ireland. It was terrible weather — windy with crazy waves. But I was so excited. I thought it was the coolest thing in the world.

At the beginning of my career, I definitely had a huge passion and motivation to do this. But I just didn’t have the experience. I was really considering retiring completely from diving, because I had just had a terrible second season. That year, Red Bull happened to source athletes for a permanent spot on the tour from whoever performed best at the FINA Diving World Cup. I think I was ranked 12th or 13th in the world, so, far off from the top eight to make it on the tour. But I had the competition of my life and won a bronze medal at the FINA World Cup, which earned me a tour spot for 2019. My way of getting on the tour is definitely not the same as most of the other athletes. I got so lucky, in a way. Five years later I’m fighting to be in the top three. It’s been a journey.

Molly Carlson: For me, I got onto the tour after a solid year of training in the Montreal Olympic stadium with a coach. We pushed extremely hard and tried to find a full list of competitive dives to perform in videos, which were then sent to the person that selects the athletes for the tour. He was super impressed and put me on the very first stop in the 2021 season. I got into high diving in the first place because I had a lot of wrist injuries. In my life of regular diving, I did 10 years of junior competitive international team and Canadian diving. The injuries piled up. I was almost ready for a change to go feet-first, which segued perfectly into high diving. It’s exactly 10 meters of diving, and then you add just a rotation to land on your feet. So, the transition has been pretty exciting, and my total 12 years of regular diving as a kid definitely helped my high diving today.

What’s the most important part of the body to train for cliff diving?

Smart: The brain. I’ve been diving for about 21 years now and I’ve done all the technical and physical work. But mindset separates the good from the great and the great from the best. Honestly, it’s something that I’ve even been working on this season. I used to take a very emotional approach to diving. I thought it was really important to want it so badly, and if I didn’t want it then I didn’t care enough…but ultimately, I still wouldn’t get it. That created a really toxic cycle. This season I’ve taken a totally different approach, where I’ve tried to eliminate emotions completely and focus on doing the dives and trusting my training.

Carlson: I agree. It’s the brain. This sport isn’t for the mentally weak — you have to train your brain to be comfortable with fear, with heights, with constantly challenging itself. Of course, you need to be physically strong and able to recover quickly from high impacts. But mentally you need to be 100% there, so that every time you jump off that platform, you’re as safe as possible, and therefore, doing the best dives possible. From a personal physical perspective, though, I’d say knees are the weakest part of my cliff diving career. My ankles are pretty strong, but the next thing to absorb impact is my knees. I’ve really been working on that; making sure my knees are top quality is the most important part of training for me.

How long does it take you to master a new dive?

Smart: Learning new dives is really scary. When I first started, I learned 10-12 dives within a matter of weeks, and it was super exciting to be progressing so fast. But all it takes is one accident, and you can lose all that progress and confidence. I got lost in a dive and landed pretty flat on my back from 20 meters — my legs were so bruised, and my skin welted and blistered. A couple of weeks later, I competed in my second-ever wildcard, and definitely felt the pressure. You assume everyone is thinking “Will she be able do this dive that she just crashed on? Or will she crumble?” I still get nervous performing that dive (my back double triple), even though it’s my most consistent and favorite one. After a major accident happens, you have to take a step back and really slow down on learning new dives. You need to get back into your flow and comfort zone.

This season, I finally built up that confidence again and learned a new dive: a back armstand dive. I received a lot of negative feedback about learning the dive, due to its complexity, but the technique I use to perform it is natural and comfortable to me. I finally said, “You know what, I’m not going to listen to anyone else, I’m ready to listen to myself and my body and mind.”At this point in my career, I’m not only diving, but I’m also coaching athletes as well. And from a coaching perspective, I really don’t think it’s a good idea to do more than one new dive every couple of months — certainly not more than one new dive per competition or stop. New dives are mentally exhausting. Sometimes, when people get really excited, they forget that they’ve just used all this mental energy. That’s when accidents happen.

Carlson: To learn a new dive in the world of high diving actually takes a lot of mental and physical preparation…and especially to master it. I actually learned a brand new dive this season; it had the degree of difficulty of 4.4, which is one of the most difficult female dives competed this year. This was the front quad half Pike and I debuted it all over my social media, showing of all the steps that it took to learn. During the offseason, my coach and I did over 20 different levels of preparation dives, just to perfect this brand new dive off the 20 meter platform. It was a lot of fun, but it’s stressful to push yourself to brand-new limits. This was also really difficult mentally, because I went into the season thinking it would be an easy dive to compete. But the first time I competed it, I landed short of vertical, even though I was higher than 20 meters. I thought I had so much space to land it.

It’s just mentally draining to add a new dive to a competition. Most athletes add one new dive per season. With the length of the season being back-to-back competitions, it’s rare that someone will add four brand-new dives every single time, due to the little reps that we get to do. Performing the same stable dives, which you know how to execute, can definitely help increase your chances of landing on the podium.

Walk me through the weeks leading up to a competition.

Smart: The offseason is a grind. I lift weights in the gym, do dryland flips on the ground and trampoline, and train in the pool. During the season, it’s more about maintaining a healthy diet and making sure that I get good sleep. Over the past five weekends I’ve had five consecutive competitions. After a competition, I try to take a full week off from doing anything physical, to give my body the time to recover. A single high dive competition feels like I ran a marathon. I feel it throughout my entire body. A lot of times I don’t even train between competitions. I really have to rely on my offseason training and keep my mind clear to visualize my dives, so that when I do step back on that platform, I’m ready to go.

Carlson: What’s difficult about the tour is there’s so much travel and so many competitions back to back, that you actually lose your routine — you lose a lot of sleep and a lot of recovery because flying around the world can be so hard on your body. It’s crucial that I make time for myself on tour to recover. We have medical professionals on the circuit that come along with us, and we make seeing them a priority. If we don’t, our injuries can accumulate and sneak up on us near the end of the season. For me, diet and sleep are particularly important. My gut really struggles with all the travel, so I have to watch what I eat. I work with my nutritionist virtually, especially leading into events like Italy, where basically the only options to eat are gluten and dairy. Mental health is also important to my general preparation, and I work with my psychologist on my anxiety throughout the weeks of competition. This is something I absolutely struggle with, and to have someone come along with me on the journey just keeps my mind fresh and calm leading into every competition.

What’s your favorite site you’ve dived at?

Smart: Every stop on the tour is so unique. Each place has its own culture and history and is just so different. It’s hard to say which place is my favorite, but one of the places I’ve enjoyed the most is Mostar in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It’s a very special place because there’s so much history in the area around the sport of high diving and cliff diving. The locals do it and teach people how to do it. When there, it feels like we’re actually coming in as part of their culture. On a personal note, I got my first ever podium at the Mostar stop after being in the hospital the day before (from food poisoning and migraines). It’s a special place for me because it taught me a lot about myself and really how far I can push myself, which has helped me in all aspects of my life – coaching my business, my family, whatever it is — I know I can do more than I think I can. Mostar is just a really, really unique place and it’s been a lot of fun to go there.

Carlson: My favorite site would probably be Boston — and the results speak for themselves. That’s where I won my first ever event, at the start of of the 2022 season. It was just a dream come true. I worked so hard in the offseason to make that happen and was so happy about that result. Also, it was the first time I ever competed in North America and we all kind of felt like superstars. For so long, we’ve been sharing our journey in the sport of high diving virtually. So many of my followers came out to the event and were excited to meet me in person. To dive in front of my family for the first time, in front of my followers, and to be in front of a crowd that supports you 100%…it just felt like Ellie and I were in our environment. It was really special.

How long do you expect to be doing this?

Smart: Something that makes high diving different is that, yes, you have to master a technique and a skill, but it’s also something that you don’t do very often. A 10-meter Olympic diver is training their 10-meter dives every week, all year round, because they can. We don’t have that option. We usually only get to do it when we’re at a competition. But because we don’t exert as frequently, I think that might allow our career to continue on longer. Also, experience is so important because we’re thrown into a lot of different conditions. A 10-meter diver is going to dive in a 10-meter Olympic pool with flat water and they know it’s going to be 10 meter. Where for us, as female high divers in particular, will go to a competition and we might be diving from 20 meters, or we might be diving from 22 meters. That’s can be a drastic difference. On top of that, it’s not always still water. Sometimes you have two meter waves, sometimes you have extremely strong gusts of wind. High diving requires a certain level of experience and knowledge that takes longer to learn and to comprehend.

I thought I would retire before I was 30. Now that I’ve had the time to invest in myself and in my career, I’m just starting to scratch the surface of what I’m capable of. I have no idea how long I’ll dive for. I’ll dive as long as my mind and my body allows me to and as long as I enjoy it. It’s something I’ve dedicated my life to. It doesn’t really seem like my diving career will ever be over. It will be more of a transition from me physically competing to moving into the business and coaching side of the sport, and serving as a mentor to athletes that find themselves wanting to become divers. I run two teams: the High Diving Institute and the Minnesota Diving Academy at the University of Minnesota.

Carlson: I would love to continue high diving until at least 2028. I’ve been hearing rumors that it’s going to be in the Los Angeles Olympics in 2028, and to be one of the first to compete in the Olympics for the sport would be a dream come true. If high diving gets pushed to the 2032 Olympics, then we’ll see if I want to keep going that long. It all really depends on how my body can handle the impacts. I think for me, a long, long journey would be until 2032. Ideally, I can compete until 2028, and then I can just slowly start to step back from the sport and help in other ways.

If I wasn’t in the sport of high diving, I would continue my journey through grad school. I’m currently in mental health counseling at Yorkville University. I love discovering more about mental health, and eventually want to counsel athletes who have gone through similar situations as I have with anxiety and pressure. Luckily, high diving has also led me to social media, where I can share this journey and my life with my brave community of followers. I’m very thankful the sport has led me here.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.