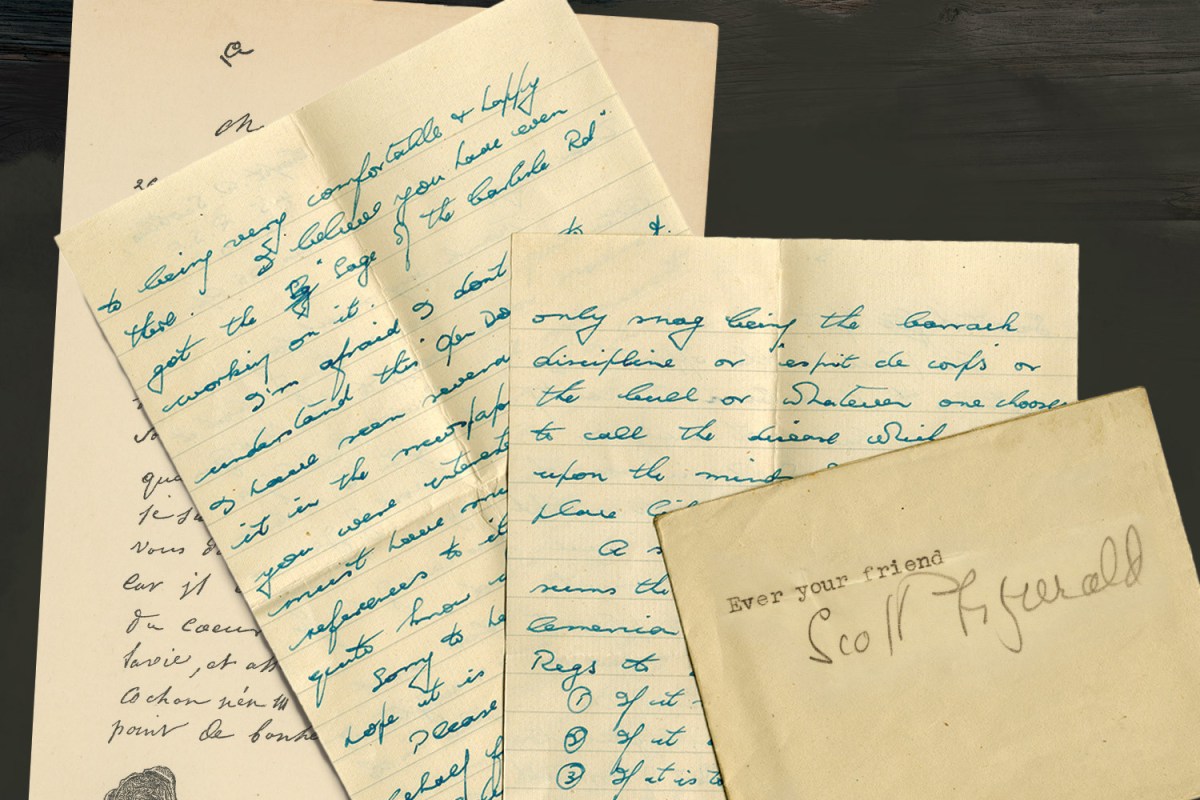

The best evidence of Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Great American Bromance is present in their personal letters. On December 6, 1927, Fitzgerald was in a mansion overlooking the Delaware River when he decided to catch up with his then-28-year-old friend. He had no clue what Hemingway was up to at the time, beyond the fact that he’d recently decided to stop selling short stories to Hearst.

“You were wise not to tie up with Hearst,” Fitzgerald writes. “They are absolute bitches who feed on contracts like vultures, if I may coin a new simile.”

The author then chided Hemingway on his rumored ongoings, writing: “I hear…that you have been naturalized a Spaniard, dress always in a wine-skin with ‘zipper’ vent and are engaged in bootlegging Spanish Fly between St. Sebastian and Biarritz where your agents sprinkle it on the floor of the Casino. I hope I have been misinformed but, alas!, it all has too true a ring.”

With the familiarity of frenemies who’ve regularly partied past midnight, Fitzgerald concludes: “I’ve tasted no alcohol for a month but Xmas is coming…For your own good I should be back there, with both of us trying to be good fellows at a terrible rate. Just before you pass out next time think of me.”

Fellas, You Should Call Your Friends and Say Goodnight

Sweet dreams, boys!Seven years later: a different time, a different tenor, a different (and more famous) letter — Hemingway writing to Fitzgerald this time, and absolutely lambasting the man for his new novel, Tender is the Night.

“Goddamn it you took liberties with peoples’ pasts and futures that produced not people but damned marvelously faked case histories. You, who can write better than anybody can, who are so lousy with talent that you have to — the hell with it. Scott for gods sake write and write truly no matter who or what it hurts but do not make these silly compromises.”

This letter has long been a “must read” for writers of any stripe; it’s rife with advice on the writer’s process (“I write one page of masterpiece to ninety one pages of shit. I try to put the shit in the wastebasket.”) But it’s awfully personal, too, and a fascinating companion to the 1927 letter. Hemingway writes: “I’d like to see you and talk about things with you sober. You were so damned stinking in N.Y. we didn’t get anywhere. You see, Bo, you’re not a tragic character. Neither am I. All we are is writers and what we should do is write.”

Of all the conclusions to be gleaned from those startling lines, here’s a simple one: these two kept in touch. Hemingway and Fitzgerald wrote letter after letter to each other, their encouragement, sarcasm, playfulness or irritation ebbing and flowing in accordance with the years. What they’re tackling on the page (ambitions, alcoholism, aging) can veer grand, but the simple act of writing a letter isn’t grand at all. It’s everyday, it’s customary; it was necessary for their relationship to survive the gulf of distance and change between them.

At first, Hemingway and Fitzgerald’s letters come across as distant relics. Compared to the modern modes of communication that we’re familiar with, those letters seem closer in DNA to missives sent between Voltaire and Frederick the Great, or Thomas Jefferson and John Adams. Or we might think of the dispatches that boys on distant battlefields sent to their friends and family back home.

And yet: ink and paper still exist. The postal system’s down, but not out. What could we gain — what could men gain, in particular — from reviving the form?

Why It’s Imperative You Find Yourself a Third Place

Bistro, cafe, library: whatever it is, protect and cherish itThe Stakes

Middle-aged men are in a “friendship recession.” The demographic is less likely to have friends than it did in 1990, and these men increasingly rely on the significant others of their significant others’ friends in order to make or maintain friendships. It’s all starting alarmingly early in life, too; according to a report from the American Perspective Survey, “more than one in four (28 percent) men under the age of 30 report having no close social connections.”

This sort of loneliness can be crippling — for both the brain and the body. Nearly a fifth of all cases of depression can be traced to loneliness. People with robust social connections, meanwhile, record lower blood pressure and on average, live up to 22% longer. When the situation is this serious, shouldn’t all possible solutions be be on the table? Even methods that feel offbeat, initially uncomfortable or even…anachronistic?

Intimacy > Immediacy

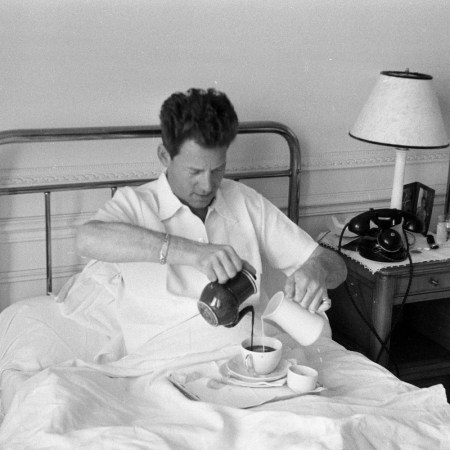

According to Matthew Schubert, a mental health counselor who owns and operates Gem State Wellness, the beauty of pen pal correspondence actually lies in its lack of immediacy. “Middle-aged men have demanding schedules,” he says. “This liberates them from the urgency of real-time exchanges, granting them the freedom to respond at their own convenience.”

In this vein, letter-writing wouldn’t represent the entirety of one’s communication with peers, but constitute the best part. It’s the anti-social media. Think: thoughtful questions and considered answers, all given room (and time) to breathe. This routine can foster a level of intimacy that is uncommon amongst men, which, experts explain, is directly feeding today’s connection crisis.

“Men aren’t really great about expressing how they feel,” says Dr. Frank Sileo, a psychologist who’s been studying the male friendship dilemma for decades. “And when they do, they feel that they [seem] weak. So men, who are more restrictive in their emotional expression, tend to have less intimate and close friendships.”

A letter offers an opportunity to fine-tune one’s act of expression in a way that is more personal and in some ways, less permanent (assuming you’re not a 20th century giant of American literature). The letters will come and go, and over time, you’ll build a rapport, a rhythm. They’ll be a surprise you look forward to receiving, a ritual you look forward to sitting down and returning to, which requires mindful concentration and raw materials.

Pick a Subject

How do you even get that ritual off the ground, though? Schubert recommends initiating contact. “It’s as simple as grasping a pen and paper and setting your thoughts in motion,” he says. “The initial gesture will brighten your friend’s day…[and from there] the pathways of communication could reopen, breathing new life into a dormant friendship.”

What if they don’t take the hint and respond with a text, or don’t respond at all? Make sure to ask questions in your first letter, and consider including a page or two of “text,” to signify that you’re not just sending a thank you note. If you’re comfortable doing so, you could just directly ask if they’d write a letter back. There’s vulnerability in expressing that desire. If it’s not their cup of tea, that’s okay. Try again with someone else. But you’d be surprised.

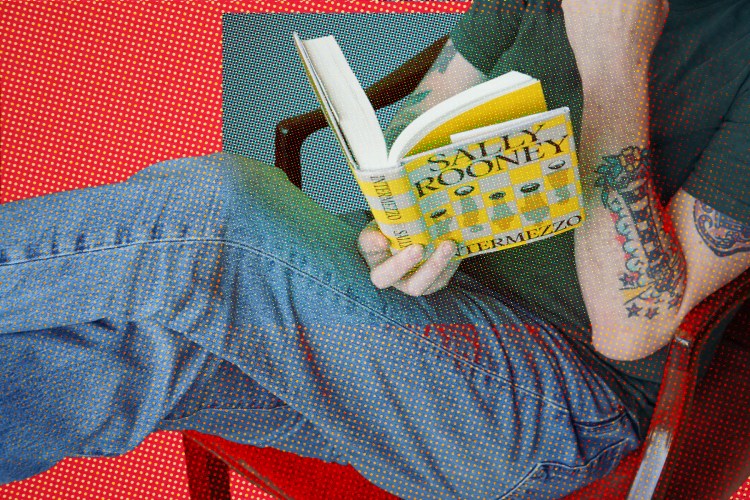

One potential strategy — while we’d encourage you to write broadly about whatever pops into your head that day, consider a common interest that you and your potential pen pal possess. In Home and Away: Writing the Beautiful Game, Norwegian autofiction extraordinaire Karl Ove Knausgaard and Swedish novelist Fredrik Home trade dozens of letters on world football.

They each favor varying styles of play (Knausgaard likes 0-0 draws, Ekelund roots for a freewheeling affair), just as their correspondence allows for different forms of letter-writing. In some instances, Knausgaard drifts far afield from their thematic through line, describing chance encounters walking up a hill near his home. Ekelund, abroad in Brazil, marvels at caipirinhas.

In its review of the book, The New Yorker wrote: “At its core, Home and Away is a story about two men doing what they can to keep a friendship afloat, even from continents away. There are times when the book drags or meanders. But there’s a truth in that, too. The joy of friendship depends on tedium, on companionship during boredom and exhaustion and what would otherwise be simple loneliness.”

Set Your Own Rules

Do postcards count? If you’re a pen pal with someone can you still text, call or email them on the side? How close do you have to be with the person to start writing letters with them in the first place? Do you have to write in cursive? Is it bad that I’ve only started writing letters to someone now that they’re in a period of duress, struggling with grief, illness or divorce? (More quietly: Is it bad if I’m only doing this because I’m struggling with grief, illness or divorce?)

To all the above, and respectfully: who gives a shit? There are no rules for this sort of thing, except for the ones agreed upon or understood between you and the person you’re trading letters with. Moreover, there are no suprapersonal judgments that should override or undermine your perception of a good thing. If you take to letter-writing, if it tethers you to something in an isolated age, then that’s that. Pursue it and don’t look back.

It may feel humbling to compare whatever you come up with to the published letters of titans named Fitzgerald and Hemingway, but that doesn’t matter, either. Anything you deem worth answering or sharing or celebrating matters. That’s why you put it on the page and in the mail. Your writing will grow as you go. And so will you.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.