What do these captains of industries past and present — Tom Ford, Jack Dorsey, Indra Nooyi, Richard Branson, Jeff Immelt and Bob Iger — all have in common?

According to various interviews they’ve given, all six claimed to have gotten by on anywhere between three and six hours of sleep every night…considerably less than the average seven or so hours slept by middle-aged adults. But then, even Donald Trump has asked, incredulously: “How does somebody that’s sleeping 12 and 14 hours a day compete with someone that’s sleeping three or four?” It’s a dog-eat-dog world. And you can’t let sleeping dogs lie.

“The problem is that there’s this idea now that there’s something unproductive about sleep, that we all must achieve as much as we can as fast as we can,” suggests Dr. Eti Ben Simon, a fellow at the Center for Human Sleep Science at the University of California Berkeley. “That’s an idea that has become dominant in most Western countries. It’s as though we’re somehow reluctant to accept that we are biological beings and not in some way above its processes.”

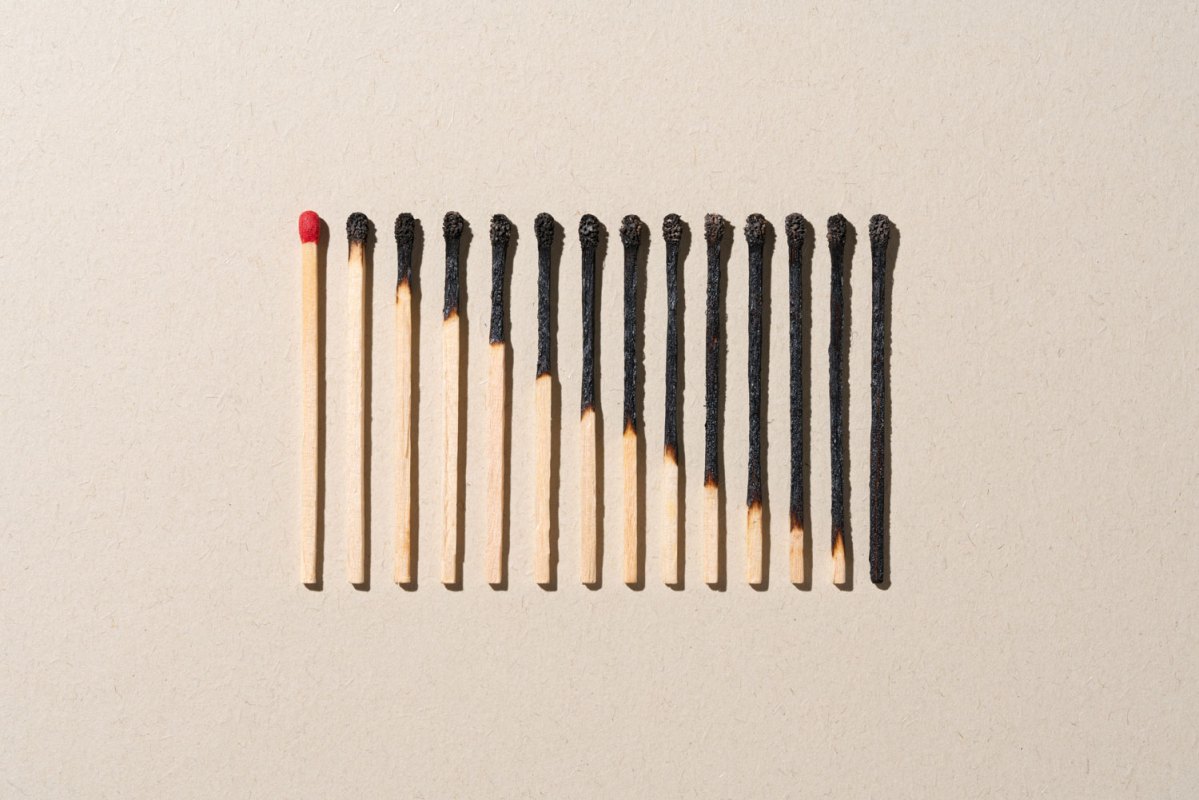

It is, she adds, hard to escape the cumulative pressures to stay awake in a 24-7, work-ethic-on-overdrive culture that frames sleep as something akin to a waste of time. There’s also the attention economy that needs constant eyeballs (as Netflix’s CEO Reed Hastings once put it, “We’re competing with sleep”), is able to provide readily accessible sources of easy dopamine hits (hello doom-scrolling!) and fosters just enough FOMO to ensure we ignore our better judgement about the sleep we need. Sleep averages have declined by two hours over the last century. That’s a pace that’s just impossible for our brain to evolve in response to.

My Year of Stress and Agitation

Ex-analysts at America’s biggest investment firms reflect on all the sleep that never cameThere’s Nothing Like Sleep Deprivation

The need for sleep is present in every single studied species. Yet human beings are the only species that will deliberately deprive itself of sleep.

James Wilson, the founder of Kipmate, a UK-based sleep training organization, says our messed-up attitude towards sleep can be compounded by a shame in expressing a regard for sleep, an embarrassment at some sleep problems (like snoring) or a machismo that says we don’t need it. “I can tell you now that if you don’t exercise for a week you’ll be fine,” he says. “If you don’t sleep for a week you’ll be dead [or, at least, very unwell]. All the other things we do to be good to ourselves — exercise, nutrition, mental health — we fetishize at sleep’s cost, even though sleep is absolutely essential.”

If we take pause — maybe even lie down for a while — humanity’s dark history shows us that we have long understood that a lack of sleep can be hugely damaging…and the more extreme the more damaging. During the witch hunts of 16th century Scotland, getting confessions prior to conviction was crucial to what then passed for due process, so “waking the witch,” as it was called, was invented. This involved depriving the poor woman of sleep for days at a time. Within just 48 hours, she was soon experiencing hallucinations, instability, paranoia; and within three days she was likely having waking dreams. Five or so days in, she had probably lost all orientation.

Sleep deprivation was similarly used by the Japanese on prisoners of war during World War II, in apartheid South Africa during the 1960s, by the British against IRA suspects in the 1970s, and by the CIA as a method of “enhanced interrogation.” Why? Because it works.

“Anyone who has experienced this desire knows that not even hunger and thirst are comparable with it,” wrote the Israeli politician Menachem Begin of his own experience of being sleep-deprived by the KGB. “I came across prisoners who signed what they were ordered to sign only to get what the interrogator promised them. He did not promise them liberty; he did not promise them food to sate themselves. He promised them uninterrupted sleep.”

Don’t Fall for History’s Propaganda

Ironically, a rather less gloomy history has given a positive spin to not sleeping as much as we should. According to Dr. Neil Stanley — the author of How To Sleep Well and of over 40 scientific papers on sleep — we’ve all fallen for the propaganda. Time after time, leaders and politicians have misrepresented their sleep hours. From Margaret Thatcher to Thomas Edison to Napoleon (“Sleep is incompatible with greatness”) official papers and biographies have revealed that these alleged “short sleepers” slept as much as the next person.

“Boastful claims to not sleeping are just a way of justifying pay packets to shareholders, or a way to appear strong and dedicated to electorates. It’s just a way to impress some audience, a way of saying, in short, ‘I’m better than you’,” laments Stanley. “Sure, that’s a seductive idea — we all want to believe that there is some secret way to be ‘better,’ though you might imagine that if all these CEOs have to be awake for 18 hours of the day to run their companies they might not be such good businesspeople. Unfortunately, the idea we should just sleep more — that it’s the one thing that will make us happier and healthier, while also, bizarrely, being the one thing we don’t do — is a message that’s up against the zeitgeist.”

The Cost of Sleep Debt

Reduced sleep duration has been linked to seven out of the 15 leading causes of death in the US, including cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, septicaemia, hypertension and depression. You might not be able to perceive these changes if you’re consistently getting, say, just an hour less every night, but scientific measurements of your metabolic health, memory, attention, concentration, cognition and other brain functions, will show a decline in performance relative to getting seven or eight hours. Ten days of sleeping one less hour a night leads to cognitive impairment the equivalent of not sleeping for 24 hours straight. Impairment actually kicks in after just 16 hours of wakefulness.

Sure, there have been some claims of late regarding certain people who are genetically predisposed to need less sleep. And like height or shoe size, there is a genetic component to individual sleep requirements. (It seem that a rare genetic mutation leads some people — and, in experiments, mice — to be natural short sleepers.) But most people who come forward claiming to have this mutation turn out to just be insomniacs.

“Science is increasingly effective in showing how a lack of sleep affects people very brutally,” says Dr. Erla Bjornsdottir, a clinical psychologist and sleep specialist at the University of Iceland, and developer of an app launching next spring to help women deal with insomnia during menopause.

“It’s why all those braggers seem to end up with Alzheimer’s,” she explains. “So many health problems are linked to not getting enough sleep, but the general public seems not to be aware of this. And yet: if sleep was pitched like a drug — one that lifts your mood, improves your performance, maintains good health, helps prevent weight gain — we would all take it. That’s what the right amount of sleep does. Instead, we’re encouraged to push through the day powered by lot of fake energy, from coffee to vaping, energy drinks to blue screen light.”

As Simon notes: while it’s a good idea to get sleep when you can, you can’t fix the accumulated damage by binge sleeping at the weekend either. Sleep experts tend stress that it’s not all about the length of sleep, it’s about the quality of sleep, too. Still, you want to be getting somewhere in that seven to eight hour zone, and try to go to/get out of bed at roughly the same times each day.

Can One Giant Weekend Sleep-In Erase a Week of Terrible Sleep?

What you should know before you doze until noon this SaturdayIt’s Emotional

It’s not just our physical and cognitive wellbeing that is impaired by not doing so either. The latest focus of sleep science is on how it also negatively affects our emotional state. Evidence from Eti Ben Simon’s research suggests our ability to process emotions and deal with challenges to our emotional stability are impaired by reduced sleep.

It puts us in a psychological state akin to anxiety, basically. Sleep deprivation makes us feel lonely, less interested in social interaction (curiously, it also makes people less willing to interact with us) and less likely to help other people. As she says, the impression many of us have that “nothing really important is happening if we’re short of time and decide to cut out sleep” is woefully misguided.

Can this impression be changed? Simon and Bjornsdottir both argue that we need a radical reappraisal of sleep to finally put the notion that less is okay to bed. For her part, Bjornsdottir would like to see sleep education for school-age children, and Simon would like to see sleep more widely reframed as actively restorative — not simply a period of time in which your body and consciousness seems to switch off. She wants society to embrace a greater flexibility towards each individual’s right to access sleep. This may be somewhat utopian. Electric lighting and central heating gifted us a night-time economy, while industrialization demanded regular working hours — killing the once-common practice of the afternoon nap in the process. It’s hard to see these two social forces relenting. There is what she calls jokingly calls “circadian discrimination” that drives everyone to align with the nine-to-five.

Eight Hours for All?

“I did a standard nine-to-five job once and it almost killed me, because I’m such a night person,” she says with a laugh. “But if we each had more control over our schedules to maximize our opportunity for sleep [when our individual bodies are best attuned to it] then that would be better for us and make us better, more productive employees. I’d like to see it become socially acceptable for people like me to offset their schedules by, say, a couple of hours, because working against your biological clock all your life just isn’t good for you.”

Wilson reckons there is a shift happening — and not because his father ran a mattress company: among his clients now are not just Premiership soccer teams, which might be expected, but also huge retail chains. They’re getting the idea, he says, that if they want to do something wellness-oriented for their workforce, talking about something that everybody does is a good place to start. “After all, companies that operate unusual hours especially want their staff alert. They want to tackle absenteeism,” he says. “There’s more and more of this kind of thinking.”

But Neil Stanley has his doubts. Most people, he observes, are now aware of the basics of keeping fit and eating well; but most people still don’t have a clue about what happens in sleep or why it matters. That’s odd for something some of us like to spend a third of our lives doing. “In the past sleep was considered a pleasure. Now it’s considered something you have to do, like a chore. It’s like there’s a war on sleep happening out there,” he says. “Whenever I give a lecture I always get asked one question: ‘How can I get by on less sleep?’ And that’s like asking a PT how to get by on less exercise.”

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.