Jesse Dufton is one of the most remarkable athletes you’ve never heard of. A member of Great Britain’s paraclimbing team, his climbing career is a testament to what’s possible within the sport: Due to a genetic condition, Dufton’s eyesight has gradually deteriorated from 20% central vision at birth to just 1% today.

He hasn’t let it slow him down. Best known as the first blind person to lead-climb the Old Man of Hoy, a famous Scottish sea stack, in 2019 — which was the subject of the award-winning documentary Climbing Blind — he’s also the first blind person to claim first ascents in the Arctic, having completed his first E2-graded climb in 2020.

Dufton spoke to us about his formative routes, the experience of climbing sightless and his hopes of becoming the first blind person to nail a first ascent in Antarctica.

InsideHook: You grew up in England’s Lake District — do you remember your first climb?

Jesse Dufton: My dad was a climber and he was involved in the mountain rescue team. He took me climbing basically as soon as I could walk. My first route was on Idwal Slabs in North Wales when I was two years old. I can’t remember that first climb, but I do remember leading my first route, in Cornwall, when I was 11 years old. Before that I remember climbing Commando Ridge in Cornwall, when I was about five. It’s not that difficult; they use it to train the Royal Marines.

What was it about climbing that drew you in?

One of the things that attracted me to it was that you get to go to these amazing places. You could be hanging from a belay on a sea cliff with a vertical drop down to the waves below you. You know, you don’t get to go to those places as a “normal person.” You find out a lot about yourself in those situations.

Like what?

Around 2007, my wife Molly and I were climbing near Chamonix in the French Alps. We topped out, we were walking back and there was a guy from another party who fell. I still had a bit of sight left and I could see a tiny little speck, but Molly saw the body just rag-dolling down the mountain. It being Chamonix, the chopper was there inside 15 minutes; it beat us to the guy’s body.

It was not a pleasant experience, but when you’re in those situations you find out a lot about how you deal with pressure: do you manage to stay calm, do the right thing at the right time, or do you lose your head?

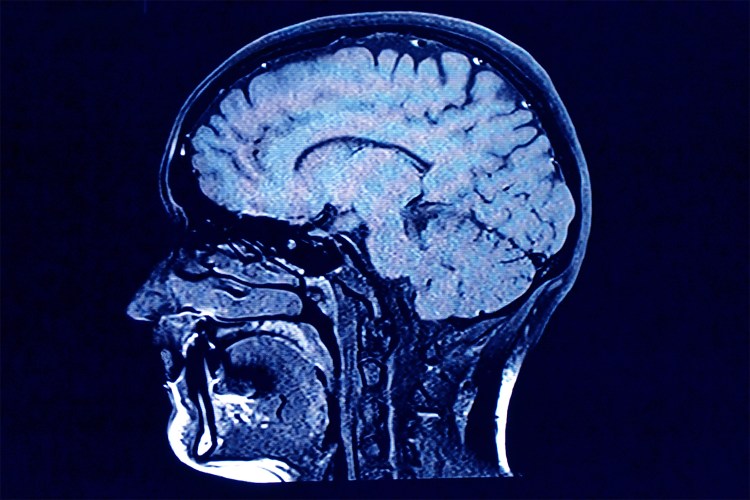

Talk me through how you lost your eyesight.

The umbrella term is cone-rod dystrophy. That basically means that the rods and cones with the light-sensitive cells in the back of my eye are dying because of a genetic fault. It’s affected me since birth. I don’t know what “normal” vision is because I’ve never seen it.

When I could see, my eyesight was never good enough to read a route. When other climbers were looking up at the route before they started climbing, I’d wonder what they were doing. It never even occurred to me that someone’s eyesight would have been good enough to stand at the base of the route and spot the handholds and plan the sequence.

Meet “Racer Tom,” the 63-Year-Old Ski Resort Folk Hero

Thomas Hart amassed over seven million vertical feet at Snowbasin this season, and he’s not done yetYou climb with Molly now and she’ll guide you. How does that work?

We’ll use radio headsets so that Molly can talk to me as I climb. Indoors, it’s very easy for Molly to see where all the holes are and see the sequence from the floor. We have a code now so she can direct me to the holds.

Outside, it’s more down to me. Molly does her best to direct me, but if you’re climbing on something like pocket limestone, which is like Swiss cheese, you can’t tell from the ground which are the good holds, so I just have to explore with my hands.

Does fear come into it?

I do get scared, but only in relation to the actual risk. A lot of people get scared when they’re actually very safe. If you’re climbing an indoor lead route, you’re pretty safe there. But some people still find that really, really stressful, especially that penultimate clip.

Outside, in situations where your life is on the line, there is fear there because you know what the consequences are if you mess up. People often think it’s easier for me because I can’t see the ground when I look down, but no, that’s not how it works.

The thing to remember is I got used to the heights when I was very young. I did go through a period where I was scared of heights — it’s a pretty intimidating environment when you’re 10 years old — but you get used to it.

What’s your proudest achievement in climbing?

One that was very special to me is Forked Lightning Crack in Heptonstall Quarry, Yorkshire. There’s a video of me doing that on YouTube. It was my first ever E2-graded route. It was harder than anything I’d climbed when I could still see a little. It felt like crossing the Rubicon.

I’d never tried anything that hard before. I couldn’t prepare myself mentally, because I didn’t know what to expect. I’d never been to the crag when I could see, so I didn’t have a mental image of it. Molly was trying to describe it to me, and she said it was steep. I didn’t realize she meant that steep. It overhangs the whole way and once you leave the ground, you can’t really retreat. It’s basically climb to the top or fall off.

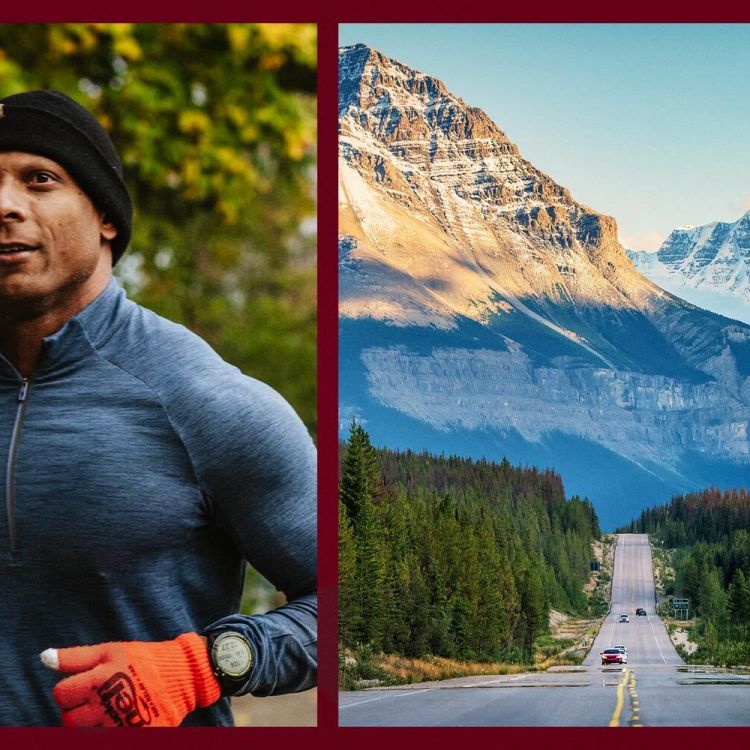

You climb a little bit slower, relatively speaking. How does that impact you?

My endurance needs to be so much better than it would need to be if I could see. I’m just so slow. If you can’t see the holds, you could easily get stuck on a tiny little crimp just before the jug, which you haven’t found. So you’re not always climbing too efficiently. I do quite a lot of training. Endless laps on the circuit board, for example.

You also made the first blind ascent in the Arctic. What was that like?

Somehow, in 2017, I ended up having five weeks off from work, so we wanted to go somewhere cool. We decided on Greenland. A large part of it was it’s easier for me to approach the objective on skis, instead of clambering through a boulder field.

We had daytime temperatures of 5°F, dropping to –22°F at night. It’s so silent. Where we were, there’s nothing for 200 miles. There are more polar bears there than people. It also never gets warm enough for the snow to partially melt then refreeze, which means it’s very powdery and insecure, like standing on icing sugar.

So the climb itself, the moves weren’t that difficult, but the seriousness of the situation and the insecure nature of the climbing made it a challenge. We knew that if anything went wrong we were on our own.

What’s next?

The big thing would be if I were ever to find the support to go to Antarctica. That’s the dream. I’ve got first blind person with first ascent in the Arctic, it would be amazing to repeat the trick in the Antarctic.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.