“I haven’t picked up a camera in weeks or months.”

That is not what we expected to hear from renowned adventure photographer Chris Burkard, even in the midst of a global pandemic. If you’re one of his 3.6 million Instagram followers, it’s an admission that will likely take you by surprise too, as quarantine measures haven’t stopped him from posting about his global travels, ranging from Russia’s Kuril Islands to the glacial rivers of Iceland.

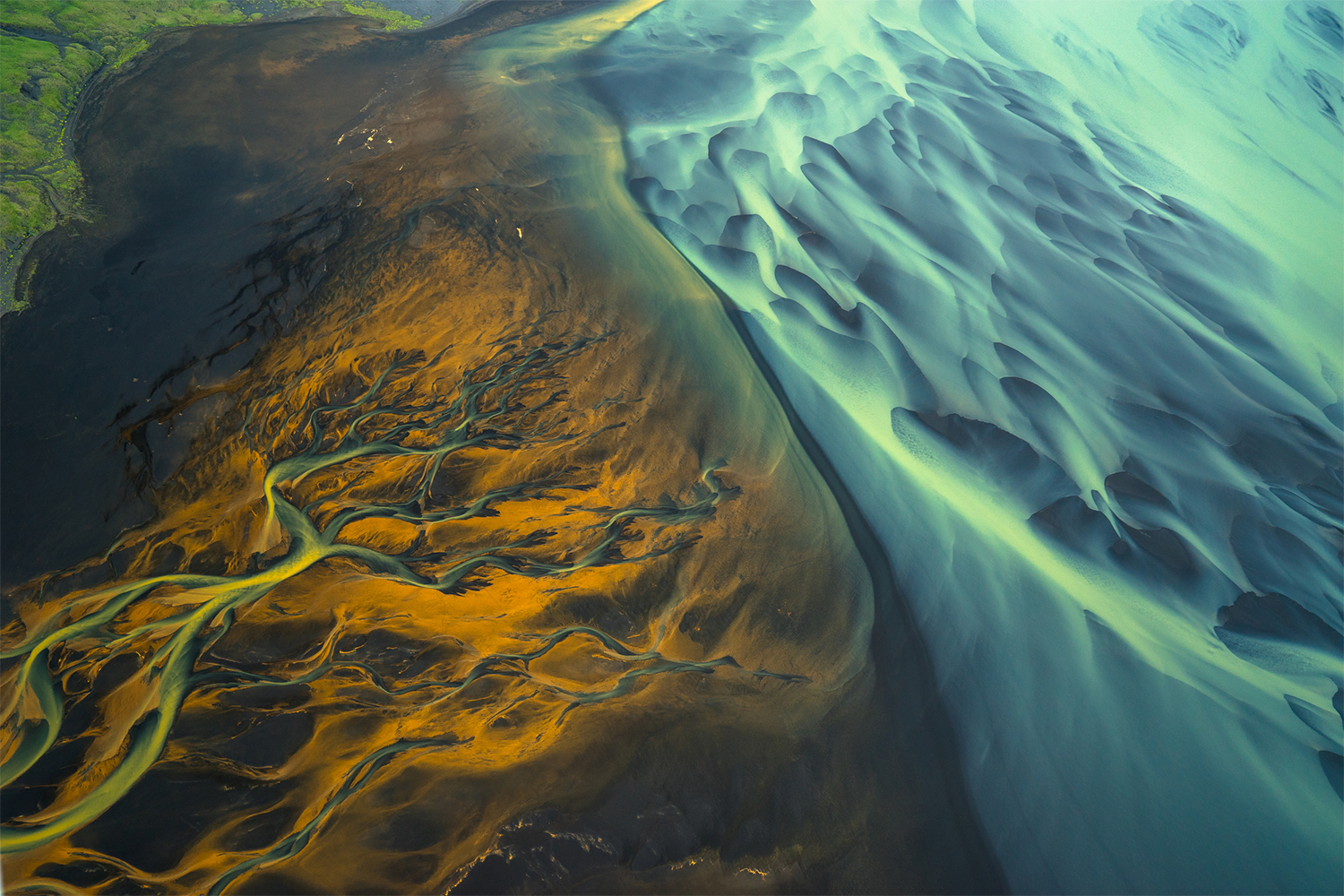

The latter make up the entirety of At Glacier’s End, his newest book. You might not know it as his from a quick glance at the cover, or even after flipping through the pages, because the tome marks an evolution of sorts for Burkard. It moves away from the “travel porn” genre that he helped create — easily recognizable, inspirational scenes that rack up thousands of likes on social media — for a more detached, almost abstract study of a specific ecosystem.

You see, At Glacier’s End is not a pure photo book like some of his previous releases, such as Under an Arctic Sky, the companion to his 2017 Icelandic surf film. Yes, it’s a passion project that includes photographs taken over a period of seven years, but accompanying the otherworldly, even Tolkienesque scenes is an important environmental, historical and cultural story from writer Matt McDonald.

We dialed up Burkard and McDonald to talk about why these glacial rivers are much more than an environmental marvel, as well as Iceland’s plan to protect them by creating a massive national park. Since it’s currently unadvisable to seek them out for yourselves, we also talked about their process, how they’d like the travel industry to change when countries finally reopen for business, and the best way to catalogue all those travel photos currently burning a hole in your external hard drives.

InsideHook: What have you both been up to the last few weeks in self-isolation?

Chris Burkard: It’s been a lot of planning and looking forward to the future. I’ve had a lot of projects fall off the table, which is fine. That’s to be expected at this point. I’ve been spending a lot of time with my kids and I’m still trying to do as much as I can to put work out there in the world. A lot of Instagram Lives. If anything, there’s a shift towards trying to promote the projects that I’ve already done, as opposed to being so caught in the daily doldrums of like, Oh well this didn’t happen, this didn’t happen. I think that’s a dangerous road to go down because you start to feel really like you’re missing out, when all you need to do is look back at the last year and realize there’s so much adventure and knowledge and learning that you can unpack from the experiences you had, this book and experience being one of them.

Matt McDonald: I’m based in Maui, and it honestly hasn’t changed that much, because primarily as a writer I’m working from home each day and we’re still allowed to get in the ocean. We’re still allowed to surf as long as we don’t congregate, which is my primary means of physical relief. I mean, my mental state has certainly changed since all this began. In addition to that, just being forced to do the personal work of living slower and not being able to just push out negative emotions with being busy or seeing friends or having a drink or whatever.

Chris, as a photographer, is shooting photos every day a ritual under normal circumstances? And what has your photo work been like under quarantine?

CB: That’s such a good question. To be honest, it’s one that people haven’t asked me much — and the reality is, no. I haven’t picked up a camera in weeks or months, besides my phone or a Polaroid camera with my kids. For the last couple years I’ve been trying to move away from the camera, to be honest, and moving towards trying to express myself creatively in other means, whether that’s speaking or writing or working on other books, and things of that nature, or directing. It’s a bummer to not pick up a camera and go out, but I’m also not super inspired to do so. I’m more inspired to take my kids and go watch the sunrise somewhere than I am to go early by myself and document that and try to bring it back to my office.

Talking about At Glacier’s End, you probably could have gotten away with doing a short intro, filling the book up with photographs and calling it a day. But there’s this environmental and historical aspect added. How did that idea come into being?

CB: I felt like I would have done this place and the overall cumulative experience a disservice had I not gone down the road of telling the story from a top-down view, no pun intended. After documenting these rivers for about seven years and learning about their issues and learning about the complications, I was asked to speak at this environmental conference that Iceland does every two years, by the environmental branch of the government. Upon doing that, I really realized, wow, this is more than a personal project, more than a pet project. One thing I realized is that trying to take the ego out of projects is helpful. There’s a real beauty that comes from collaboration and I knew I needed to reach out to somebody to help tell that story much better than I ever could. Matt and I had collaborated on other projects in the past, so I reached out to him. I knew that it was going to require a trip to Iceland, so basically Matt took on this massive role of writing the story and these beautiful 10,000 words.

Chris, you have a long history with Iceland. Matt, did you have experience going to the country or doing any work there before coming onto the project?

MM: No, I didn’t. And I think in a way that can be helpful because you can see a place freshly. As Chris said, a big part of me writing this was making sure I had been there to touch the soil, to see the colors, to feel the 60-mile-an-hour wind, to talk to the locals to get their perspective on the issues we were going to write about, and also to meet other authors and people in politics. Icelanders are actually very approachable. One of the best-known authors and environmentalists in Iceland, Andri Magnason, I just emailed him and asked if we could get lunch. And within an hour he was back to me saying, “Great, meet here on Thursday.”

The story that came out of this was really a microcosm of a bigger question that we all deal with: How do humans build prosperous communities and economies while also looking forward to their wild places, making sure that those wild places aren’t destroyed for future generations? That’s really the crux of this entire book. The photographs that Chris had taken, beyond the beautiful intricate patterns and abstract art, there’s also pictures of the dams, of the dried-up rivers, the pictures of massive destruction and reservoirs that had been created. So it’s the whole package.

When you were talking to locals and doing research, what surprised you?

MM: One of the narratives that I researched about before going over there was that after World War II, the country came into this modern world searching for an economic identity, or just an identity as a people. They’ve been farmers and fishermen, basically lived off the land, forever. The thesis we came into the book with was that long-term they want to be a country that promotes sustainable — whatever that word means — tourism as their economic pillar, not extractive industries, which is the path they were on. I toured the more popular south part of Iceland and saw the mass tourism that happened there and how not unwilling, but maybe uneducated those [tourists] were to travel to some of the farther off places, places that were a day from Reykjavik, rather than just four or five hours. There were small towns that were being threatened by extractive industries, and they were empty, but that wanted [tourists] there.

I think, at least as an American, you go to small towns and a lot of times people don’t really want me there, they want it for themselves. But I think Icelanders, at least in the conversations that I had, were seeing that as their way forward. That struck me as a turning point, at least in my research, in the sense that people actually wanted this, and you’re on the ground and talking to them in conversations, not just through political research or data that we had read about.

CB: One of the big takeaways from the beginning was this concept that, Matt and I, we’re not going to do this without the support of the government. The reality is, yes, we’re two Americans talking about very sensitive topics like environmentalism and preservation and conservation in a country that we don’t live in. But this is because Icelanders, first and foremost, they value our opinion. And I don’t mean ours, I mean every American; they value the opinion of tourists. That’s why they wanted me to speak at that conference because they wanted to hear what we thought. If you are a tourist, you have a voice, and every time you go there, you’re voting for what they should do and you’re voting for the fact that sustainable tourism is more important than extractive industries. Some of these extractive industries, it’s not something that can last.

All of the photos in At Glacier’s End were taken from Cessnas. Do you remember the first time you went up in one?

CB: Yeah, absolutely. I remember the very first experience was flying over a different part of Iceland, basically going from Ireland to Iceland. I remember looking out the window of the plane and seeing these killer patterns and being like, oh my gosh, I need to know what this is. I need to document this. I hired a small plane through a friend and met this pilot who helped me document everything in this book. He was instrumental in educating me as to what was going on. That being said, it was this lengthy process, it did take seven years. I would shoot everything out of a small Cessna, which is like the Volkswagen bus of planes. It’s this tiny little puddle jumper. The Cessna 210 has a unique design where the window opening would flop all the way up and you could put half of your body outside of the plane.

You went through thousands of photographs to pick out the best shots for this book, so if people are going through their own photos, what advice do you have for picking a perfect image?

CB: The process of making a book is so extremely frustrating. I say that in the most endearing, lovable way. I’ve suggested to every photographer: try to make a book, even if it’s just one for you. You learn so much about who you are, about your work, about everything by doing so. Sometimes you realize, Whoa, I had tunnel vision. I didn’t even shoot a photo of this and a photo of that, and that’s what would have given me the full picture of what I was trying to shoot! One of the things I love to do is pull out images that are significant to me and write a story about it. That’s one way to become a better storyteller. If you can write 500 words about this one particular photograph, it’s going to benefit you a lot.

The last question I wanted to put to both of you: since this book is centered around environmental themes, when we open the world back up to the normal, how would you like travelers to be better stewards of the planet when exploring natural wonders like the ones you captured in this book?

CB: A big takeaway for both of us is that we want people to realize the key to preserving a lot of these places is not to not go there. It is actually to experience, to go there, to fully embrace them. In Iceland specifically, there are these remote towns, these villages, these places that have converted their farms into Airbnbs in the hopes that people will come. In terms of preserving and documenting wild places, when we go to these locations with the expectation that if we don’t experience this, if we don’t see that waterfall, if we don’t get this photo, then it’s going to be unsuccessful — then our trip is doomed from the start. The goal should be to truly go to places with an open mind, do our best to get off the beaten path, do our best to go to the places that are less impacted or are not going to be as impacted by tourism, and do your research. In terms of what it means in 2020 to be a good storyteller, I think it means that anybody who has a platform, whether the voice is big or small, if you share what you love and what you care about and what you fear losing, you’re going to advocate for the preservation of these places.

MM: I’m guessing that people are going to be more selective about whether to get on an airplane in the future for quite a while, even if it’s proven to be safe. I hope that inspires people to do a little bit more homework on the places that were on their bucket list, and to support places with their visitation, with their dollars, that are moving towards objectives like in Iceland. During this quarantine, Iceland is still working as hard as they can to get those massive national parks approved, because ultimately they believe that wilderness preservation is better than damming, in a nutshell. Supporting places like that with our dollars in the future, in a rosy world, could inspire more countries to follow in Iceland’s footsteps. When people go to these places, really having a full immersive experience, not just ticking off the places that are Instagram-worthy, that’s something I’d love to see in a new travel era.

CB: I don’t think Matt and I are negative Nancys about all this stuff. Ultimately, the reality is there’s a romance to the idea that people are going to get out there and have these life-changing experiences. And I think that that’s actually a reality. It’s possible. But it’ll never happen if we don’t change the conversation around how we’re experiencing places and how we’re cultivating honest and real and holistic travel experiences. A big part of that is being the type of person that’s not just a tourist, but a traveler.

Answers have been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.