As soon as I heard that the 2021 Sundance Film Festival would not be held in Park City, Utah — or any other physical place, on account of it moving to a virtual format — I knew I wanted to attend. And I knew I wanted to be in Park City when I attended.

This, understandably, did not make much sense to the people I spoke to along the 2,200-mile drive from New York to Utah, or the Parkites I met once I reached my destination. But I had my reasons. Most selfishly, I wanted to visit my sister and her girlfriend, who moved to Park City last fall. But there were journalistic considerations too.

An independently conducted study found that the 2019 Sundance festival generated a total economic impact of $182.5 million for the state of Utah and supported more than 3,000 jobs, primarily in Park City and the surrounding area. For a tourism-dependent economy that had already been hammered by COVID-19 — resorts and restaurants closed indefinitely last March, one of their most lucrative months — it seemed, at least to a curious outsider, that the loss of Sundance would cripple the town.

The prospect of trekking there was also enticing. There’s something romantically anachronistic about driving as a means of long-distance travel, and Kerouacking east to west at this particularly fraught moment was a chance to check the nation’s temperature with a thermometer other than Twitter.

When I began my I-80 odyssey on January 22, I had no idea what kind of country I was driving into. Politically, it was more subdued than I expected. To pass the time, I counted flags and signs bearing the name of the former president; the sum never reached 20. More than a handful of bumpers bore the sappy resin of recently scratched-off stickers. Rest areas were sleepy, as were roads. Except for the trucks. During one stretch, I passed 17 semis — including three Amazon trucks — before I encountered another passenger car. Electronic highway signs illuminated each state’s most pressing message for travelers.

In Indiana: “ROAD RAGE IS NOT WORTH IT! STAY CALM, STAY SAFE.”

In Pennsylvania: “COVID IS STILL A RISK. KEEP YOUR MASK ON!”

Similarly in Wyoming: “ARRIVE ALIVE. AND THEN WEAR A MASK!”

At a truck stop near the Nebraska-Colorado border, I parked in a spot with a view of the entrance. A picture of a mask was taped to the door, but I’d learned over the last thousand miles that these signs weren’t always observed. I watched a few people come and go. Every mouth was covered. Thankful that I wouldn’t have to surreptitiously urinate in a parking lot again, I donned my mask and went inside.

Upon entering the restroom, I made eye contact in the mirror with a maskless man. He was furiously scrubbing his right foot with hand soap. It was a sweaty, dirty-looking dog. He noted my presence and returned his attention to the sink. His face was scruffy and indifferent.

I arrived in Park City the following night under a wine-dark sky. The fading sun was level with the horizon, but there was just enough light to make out the swooping contours of the Wasatch Range, the mountains that set the western edge of the Rockies and endow Utah’s booming ski industry. Perched 7,000 feet above sea level, the air in Park City is decisively cleaner than the nearby state capital, which I heard several locals refer to as “Smog Lake City.”

After a grueling drive, I couldn’t have asked for a warmer reception. We feasted on braised short-ribs and scallion pancakes and then basked in the simple joy of being in the same place at the same time. My sister poured a dark IPA from a growler she recently brought back from Montana.

“None of that three-percent crap,” she winked as she handed me a pint. (Beer in Utah is infamously weak due to the Mormon Church’s influence on state liquor laws; however, a 2019 amendment raised the permitted ABV in beers to 5%.)

The next day, I headed out to begin the research phase of my formal mission out west: reporting on Sundance, which, of course, was nowhere to be found. Beyond the economic concerns, there was also the question of what not hosting Sundance would do to Park City’s sense of self. The festival is integral to its brand, and vice versa.

“When people who are not from Park City think about Park City, they probably think about Sundance,” says Bubba Brown, editor of the Park Record, the local newspaper. “And when they think about Sundance, they probably think about Park City.”

The two share a deeply intertwined and mutually beneficial history.

“We’ve grown up together,” Andy Beerman, Park City’s mayor, tells me. “Forty years ago, Park City was not on the map with any of the big ski resorts or western destinations. We were really struggling as a mountain town. And over the years, Sundance has grown from a tiny little festival to an international draw. Park City’s gone in that same direction.”

The story of this growth is a fascinating one for anyone interested in how a place becomes a destination. Before Park City was a mountain town, it was a mining town. After the Second World War, the price of silver plummeted and a great exodus ensued.

“We had about 20 years where we damn near became a ghost town,” Mayor Beerman says. “We actually got listed in a book as being one of Utah’s ghost towns.”

Thanks to the resilient and enterprising spirit of the remaining Parkites, that destiny was averted. The miners and their families accepted the cold reality that they would never again be miners. That hurt. But as they looked over their beautiful home, which, at that moment, must’ve felt like it was resting on Utah’s famous quicksand, they knew how to save it. The solution was in the land, or rather, on it: upon those idyllic snowy peaks, their future revealed itself.

In 1962, representatives from the United Park City Mines Company delivered a presentation to Utahns Inc., a new organization aimed at boosting the state’s travel industry. The miners shared their intention to build a ski resort on 10,000 acres to which they owned the mineral rights. They noticed that skiing was becoming increasingly popular in other western states; in the postwar boom, tourism was one of the economy’s fastest growing sectors. Why shouldn’t they cut a piece of the pie? The Area Redevelopment Agency granted the miners a loan, and Park City’s reconstruction was soon underway.

“Tourism was alluring because it was a non-extractive industry that had the advantage of attracting dollars from outside the state,” wrote Susan Sessions Rugh, a history professor at BYU, in a 2006 essay on postwar industry in the American West. “Those dollars not only benefited the purveyors of tourism, but also resulted in tax revenue for the state.”

Treasure Mountain, Park City’s first ski resort, officially opened on December 31, 1963. Boasting the country’s longest gondola, it quickly became a magnet for local skiers. Drawing out-of-state travelers, however, proved more challenging. Tourism, at least on an industrial scale, does not occur organically. It may be manufactured by developers and architects who subscribe to a Field of Dreams ethos (“If you build it, they will come”), but it only becomes a viable commodity when marketed effectively.

Promoters of Utah’s inchoate ski industry faced a PR problem, as demonstrated by this excerpt from Where to Go in Western States, a pamphlet published by the Chicago Motor Guide in 1940: “[Utah is] the home of the Mormons, of their world-famous tabernacle, of the Great Salt Lake, of hardy pioneers and their rugged descendants.” If Utah wanted to reinvent itself as a cultural hub and winter wonderland, it would first have to change that perception.

Around the same time, Robert Redford was making moves in Utah. Inspired by a motorcycle road trip, Redford purchased 5,000 acres in Provo Canyon. In 1969, he built a ski resort and named it after his character in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. In 1978, he hosted the inaugural Utah Film Festival in Salt Lake, hoping to raise the profile of American independent cinema while promoting Utah as a desirable shooting location for filmmakers. Midnight Cowboy and Deliverance were two of the titles to play (retrospectively) that first year.

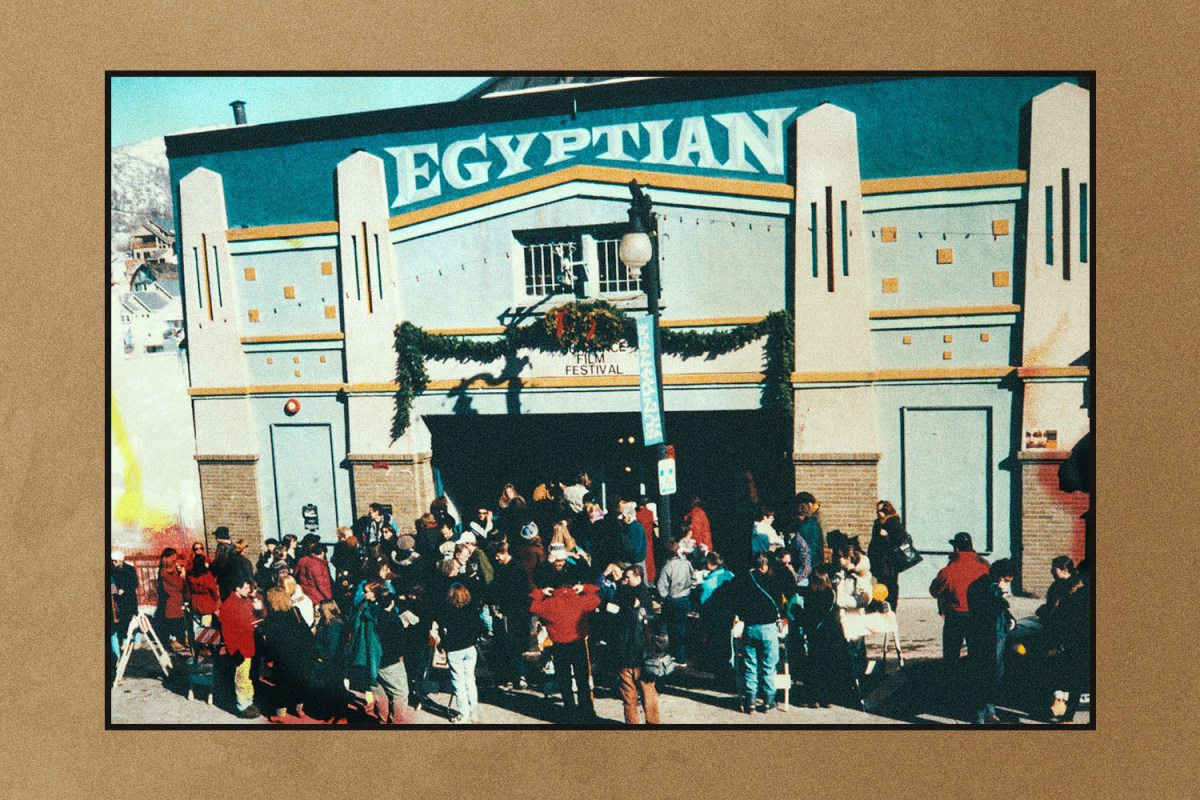

1981 was a milestone year. Redford founded the Sundance Institute, a nonprofit dedicated to nurturing the craft and growth of independent film, and he moved his festival to Park City, changing the date from September to January in the process. The conceit was that a film festival in a resort town would garner more attention from Hollywood. Redford and his team renamed it to reflect their broader commitment to American cinema. The U.S. Film and Video Festival officially arrived in Park City on January 12, 1981.

Anticipation gripped the town in the weeks leading up to the festivities. Coverage in the Park Record captured the exuberance Parkites felt at the prospect of hosting Hollywood. “National Press to Cover Film Festival,” proclaimed a headline on January 1, 1981. Community leaders understood that the spotlight was a huge opportunity for their ambitious town, which had made promising strides since pivoting to tourism in the ‘60s but hadn’t yet caught fire.

A week later, the local paper ran an editorial aimed at galvanizing locals and courting their visitors: “Park City should feel proud to host this prestigious event, and we on the Record staff would like to welcome all the directors, writers, actors and cameramen who will be here for the third annual Film Festival. And we should add that Park City, hopefully, will prove to be an ideal location for such an event, away from the hustle-bustle of city life.”

The marriage between the town and the festival, which permanently changed its name to Sundance in 1991, had an alchemical reaction. Sundance grew to rival the prestigious European festivals, maintaining its commitment to American indie cinema with debuts from upstart directors like Quentin Tarantino and Steven Soderbergh while widening its scope to include international and non-narrative films.

“I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that Sundance spurred a renaissance for documentaries,” Nan Chalat-Noaker, the Park Record’s longtime former editor, tells me via email. She arrived in Park City in 1977 and covered the festival every year until she retired in 2017.

As the festival surged, so too did Park City’s economy, and its cachet as a destination. In addition to Treasure Mountain, which is now called Park City Mountain Resort, the development of other resorts like Deer Valley and Alta helped put Utah skiing on the international map. The long game paid off when it was selected to host the 2002 Winter Olympics.

“Branding the state was a key strategy in Utah’s transformation from a rural backwater to a world player in the tourism enterprise,” wrote Rugh, the BYU historian.

Since the Olympics, home prices have skyrocketed and marketing dollars continue to stream in and out of Park City. Every winter, restaurants and shops make big money by renting their space to corporate sponsors during Sundance. Historic Main Street, which still has the bones of an old mining settlement, transforms into a buzzing cosmopolitan hive. Celebrities and civilians intermingle at sponsored lounges and parties, with red carpets rolled out in front of the Egyptian Theatre each night to welcome the arrival of A-list dignitaries.

“Very wild,” is how one actor-director describes the festival’s nightlife. “There’s a lot of anxiety because you’re waiting for reviews to drop and you’re nervous about distribution and just exhausted. And your people are constantly telling you not to drink too much because of the altitude, but everybody just seems extremely drunk all the time.”

Another director laughs as he recounts the night his friend partook in “extracurricular activities” with the guys who made Super Troopers, which premiered at Sundance in 2001.

While mirth abounds every January, the festival also brings its share of headaches for locals.

“It really is a huge impact for a town of 8,000 when we’ve got over 100,000 people here,” Mayor Beerman says. “It definitely creates traffic and congestion and lines in the grocery stores and restaurants.”

Such inconveniences, however, are fleeting when compared to the massive injection of cash and tax revenue that has become a reliable line item in the Park City ledger.

“At the end of the day,” the Mayor continues, “we’re a tourist town. We like the energy, we like the excitement, we’re dependent upon the economic benefits of it, so I think there are always tendencies to complain about those sorts of things, but we’re gonna miss them this year.”

The festival, which consumes the town for 10 days every winter, typically generates 10 to 15% of the annual revenue for many service-related businesses. There is no way to fill the hole this will leave in Park City’s economy in 2021. But unlike cities and industries that suffered mightily when major events were canceled abruptly last year, Park City was not caught off guard.

“Sundance was very transparent and forthcoming about sharing information about their plans for months and months leading up to the festival,” says Jennifer Wesselhoff, president and CEO of the Park City Chamber.

That gave City Hall and Main Street time to brace for impact. The Budget Department adjusted revenue projections for the upcoming fiscal year, and business owners steered their ships away from the eye of the storm.

“I won’t lie and say that it hasn’t been hard for our businesses to adapt and figure out new ways to operate,” says Wesselhoff, who moved to Park City last fall after leading Sedona, Arizona’s Chamber of Commerce for 13 years. “But what’s been so overwhelming for me to see in the community in such a short time has been this spirit of collaboration, this spirit of partnership, this idea of trying to support each other.”

Unlike some other places, Park City has an evolutionary ability to withstand economic shocks.

“We’re a town that’s used to booms and busts,” says Mayor Beerman. “First as a mining town and then as a ski town. We’re always depending on snow conditions and we’ve had some drought years. We’ve gone through the dot-com bust and real estate crash. And so, given time to prepare, most of the businesses in town know how to hunker down.”

At Yuki Yama, a popular Main Street sushi restaurant, owner Matt Baydala says business was down almost 30% in January. He attributes that more to COVID-related restrictions than absent Sundance foot traffic, though.

“Don’t get me wrong, [the festival] brings in a tremendous amount of revenue,” he says. “During Sundance week, we probably seat about 500 people a night. Right now we seat about 140 in our restaurant for the whole day. So obviously those are huge numbers.” An uptick in takeout orders has softened the blow.

At this point, the landscape for most of Park City’s restaurants is challenging, but not existentially dire.

“We’ll be okay,” Baydala says. “We’ve done the things that we needed to do. We’ve put money away and we have a great relationship with our landlord, who’s also our business partner.”

COVID has significantly disrupted Park City’s service-related workforce. During a typical winter, Baydala says his payroll includes 60 employees. This year, it’s around 30. Many businesses have made similar reductions. Although Summit County’s unemployment rate soared to 20.4% last April, a record high, it’s now under 7%. That’s partly due to the Trump administration’s protectionist ban on J-1 foreign work visas: Park City’s resorts and restaurants typically rely on J-1 workers to staff their seasonal positions, and the ban actually helped stave off the kind of sustained unemployment that can hit tourist towns particularly hard during a downturn.

As I walked through Main Street during Sundance week, I was surprised by how bustling it was, COVID be damned. More than 350 businesses had signed the Park Chamber’s “Stay Safe to Stay Open” pledge, and they were all doing a good job enforcing mask compliance inside their establishments.

Last year, the independent film world found itself in a similar position to Park City, rattled, underfunded and worried about its future. It was unclear what kind of impact the pandemic would have on festivals and the indie economy at large.

“Festivals are kind of the initial gatekeepers of potential distributors,” says filmmaker Noah Hutton. “They’re crucial for small films.”

When most festivals were canceled last spring, filmmakers had to decide whether they wanted to share their work virtually or wait for a live premiere.

“Some films decided to hold and not show to anyone through the virtual platforms at South by Southwest or any festivals after that,” said Hutton. “And then there were films like ours, Lapsis and The Surrogate, that said, ‘Onward. We’re going to make the most of this moment.’ And that’s what we did. So we ended up having a great year — as great as we could — with virtual festivals. And we were lucky to get a lot of good reviews and get a distributor in the process.”

(Lapsis, for which Hutton recently received an Independent Spirit nomination for best first screenplay, is currently streaming at theaters across the country. It’s a compelling world-builder of a movie that satirizes the gig economy with ingenuity and artistry.)

But there were plenty of filmmakers who decided to keep their work on the sidelines.

“The market felt too chaotic,” says filmmaker Taylor Hess, who produced Lapsis and The Surrogate and is married to Hutton. “Nobody knew if buyers were going to be buying, and some filmmakers didn’t want their films to just be screening on laptops and TVs. Festivals are the first time in the life cycle of a finished film that the filmmaking team gets to experience the movie with an audience. They can feel how it’s resonating and get feedback from the industry.”

Clayton Ross McDougall, a photographer and director whose short film Cold Pizza premiered at the Montana Film Festival, believes the audience misses out when watching from home too. “Sure you can sit on your couch alone or with a couple friends and be cozy,” he says, “but that’s so different from watching in a theater with a huge audience, where the punchlines are gonna hit way harder and the emotional beats are gonna be much heavier because everyone’s having the same communal experience at the same time.”

This live experience is vital for generating “buzz,” that ethereal festival vapor that wafts across the negotiating table as filmmakers and distributors try to strike a deal. How well would a virtual festival, both sides asked in the months leading up to Sundance, create and maintain buzz?

Quite well, it turns out. Led by first year director Tabitha Jackson, Sundance organizers worked tirelessly to construct a digital world. Premieres played at fixed times and were followed by live Q&As where the audience could engage with the cast and crew. The lineup, which I wrote about last month, was world-class. Limiting the number of “seats” for each premiere created an air of exclusivity. Chatrooms that popped up before and after a screening gave attendees a chance to socialize, trade recommendations and talk up their favorite films.

Fears that the virtual format would impede dealmaking turned out to be unfounded. A number of films that entered the festival without distribution have since found homes. CODA, which won several big awards, became the most expensive festival acquisition in the history of Sundance when Apple edged out Amazon to secure worldwide rights for $25 million. Even though Park City was quieter than normal, virtual Main Street was humming. Sponsors hosted talks, lounges and other more playful events, like a virtual karaoke bar. The loyalty of the sponsors was impressive given the uncertainty that loomed over the industry in the preceding months.

“Film has played a crucial role to many in the last year, offering a glimpse of temporary relief and escape from today’s world,” Canada Goose, a longtime sponsor, told InsideHook in a statement. Their iconic jackets have long been a fixture at Sundance and on film sets everywhere. The annual Female Filmmakers panel, which Canada Goose hosted with IndieWire, was particularly special this year, considering 50% of the festival’s entries were directed by women.

Creating community in an exclusively digital space is not easy, but festival organizers deserve credit for their efforts. Using the website that had already been developed for New Frontier, Sundance’s innovative virtual-reality program, they designed a space for attendees and filmmakers to mingle after premieres. They named this space “Film Party.”

Film Party looked like a bar you might encounter in The Sims. When you enter the portal, you assume control of a stickfigure-like avatar. The avatar’s faces feature crudely cropped photographs of attendees, and they sashay about a glass floor that appears to be floating in outer space. Using your keyboard arrows, you can walk around the room and approach other avatars. You can also go sit at the bar by yourself, which is what I was doing the first time another avatar approached me.

I felt immense social anxiety as this floating visage drew closer. A message flashed on my screen asking if I wanted to accept a chat invitation. Assuming it would be a typed chat, I hit yes. And that’s when the green light next to my computer camera flashed on. “Oh shit,” I blurted out. I was not excited about the prospect of video-chatting with a stranger. I started bashing keys in a futile effort to abort.

My avatar’s photographic face was replaced with a live video stream from my computer. “Oh shit,” I said again. None of the keys I pounded would extricate me from this unbearable meetcute. The space bar made my avatar hop up and down. I decided to keep hitting it, which seemed preferable to inertia. Maybe I could jump out of the chat. “Dammit,” I muttered.

A disembodied woman’s voice said my name. I froze. The voice spoke again, “Everything okay?”

I now saw that the voice was not, in fact, disembodied. It belonged to a woman who was speaking through the face-video of another avatar.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “It’s not you. This is just unexpected.”

She gave a forgiving laugh and we ended up having a pleasant conversation about a movie we both watched earlier that day. Her name was June. June had attended several previous Sundances, so I was curious about how this virtual one compared.

“Well, I’ve already seen so many more films this year. The quality is just as high, and the viewing is very relaxing,” she said. “The in-person experience is much more stressful. It’s really hard to get to venues in the snow and traffic. But I miss the parties. There were a lot of those hazy but unforgettable nights.”

The surprise video chat was an introvert’s nightmare, and I’m not sure I agreed that the virtual festival was entirely stress-free, but I understood June’s point. Lots of festival veterans I spoke to expressed a wistful nostalgia for years past.

Nan Chalat-Noaker, the now-retired former editor of the Park Record, decided not to attend this year. “I guess it was because, for me, so much of the experience included the challenge of getting to the venue,” she says. Baking cookies for friends in exchange for parking spots, riding in packed shuttles and standing shoulder-to-shoulder in ticket corrals with interesting looking strangers were all part of the rush.

She is awash in memories. Like the time she sat next to Robert Redford at brunch. (“Out of politeness, he said he hoped I liked his movie. I literally started stuttering.”) Or the time she was walking with Roger Ebert on Park Avenue when a young film student chased them down and foisted a VHS tape onto the famous critic (“Ebert was so gracious about it and promised to watch.”) Or the night she descended into a Main Street basement that was operating as a New Frontier venue. She was there to check out an early version of a virtual-reality headset. (“Turned out to be displaying a very artistic orgy. Yikes.”)

While this year’s virtual festival received wide praise, with some attendees going so far as advocating for it to become permanent, there is no question that Sundance will return to Park City in 2022 assuming the national health outlook improves. The town and the Sundance Institute have a formal agreement for Park City to serve as festival headquarters until 2026. At that point, however, the exclusive relationship could change.

“I do not have any inside information on the future,” Chalat-Noaker emphasizes, “but, personally, I feel Sundance has reached capacity here and perhaps offering satellite venues in cities around the country will allow the festival to burn even brighter by giving more filmmakers exposure to more audiences. But I also hope that it will remain a core presence in Park City.”

Most Parkites feel the same way. The inextricable duality of the town and the festival makes it hard to imagine a future where they aren’t the center of each other’s universe. They’re two organisms that have evolved as one; each is indebted to the other for its life and its success. But while their growth over the past four decades has gone hand in hand, their growing pains and the challenges they now face may be cause for divergence.

For Sundance, changing the festival’s location may help it reassert its indie identity, which some industry observers say has waned. A common critique I heard while researching this story is that Sundance has lost sight of its founding mission by increasingly kowtowing to Hollywood.

“It gets a little more off track each year,” one director says. “Like Palm Springs was the big Sundance hit last year. And nothing against Andy Samberg, he’s hilarious, but he’s already famous and established and has connections. So you’re getting more celebrity vanity projects instead of independent filmmakers who people haven’t heard of. It’s a little upsetting. It seems like Sundance is more geared towards these people who already have connections and money and can make big films instead of the little guys just trying to get their start.”

Such criticism is fair if you judge Sundance purely on the aggregated merit of its lineup. This year, Robin Wright’s directorial debut, Land, dominated media coverage leading up to the festival. As someone who sat through the beautifully shot but painfully soulless film, I can tell you that there is no way it was objectively one of the best 73 entries that the programmers culled from the 3,500 feature submissions. But stars bring sponsors, sponsors bring money and money keeps the carousel spinning.

In Sundance’s defense, the festival’s lineup has not veered as mainstream as some detractors claim. More than half of this year’s entries, programming director Kim Yutani reported, came from first-time directors.

“They’ve been able to keep their toes in both the Hollywood and independent markets,” says Hess, the Lapsis producer. “I think they’ve straddled that line pretty well.”

There is, nevertheless, an aroma of posh exclusivity that engulfs Sundance and Park City every winter. Some people find it delightful, others worry it’s noxious. If the Sundance Institute ultimately decides this is something they want to change, moving or adding venues could help diffuse the stuffy air while making the festival more inclusive and accessible. With Tabitha Jackson poised to direct the event for years to come, the Institute has a capable and visionary leader to oversee this kind of transition.

For Park City, there is obviously a monetary incentive to host Sundance for as long as possible, but this year proved that the town can endure without it. Maybe there’s an argument to be made that it’s actually in their best interest not to serve as the festival’s exclusive venue. Being so economically dependent on a single event creates a high level of exposure risk should that event go awry. There are also more systemic problems that the town needs to solve.

If you ask any Parkite about the most pressing issue facing their community, chances are you’ll get one of two answers: traffic or affordable housing. The latter is not unique to Park City. It’s the same story in every resort town across the country. Tourism dollars bring revenue, but they also drive up the cost of living, making it prohibitively expensive for many year-round residents. Park City’s population is 8,000, but 15,000 service workers commute into town every day.

“The real-estate prices have gotten so high that a typical blue-collar or middle-class worker is not able to afford real estate in Park City,” says Bubba Brown, the Park Record’s editor. “There are a bunch of efforts underway to address that both at the city level and at the county level, but it’s just such a major problem. I think everyone’s found it challenging to make a ton of real impact to reverse it.”

Changing the nature of its relationship with Sundance could give the community the time and space it needs to more adequately confront this issue. Yes, it would result in lost revenue in the short term, but taking its foot off the growth accelerator could help the town strengthen its long-term position. With another Olympic bid in the works, Utah’s status as a premier international destination is secure. Using the next few years to prioritize local issues over economic growth might be a smart strategy, even if it’s not the most profitable one.

But what do I know. These are just some of the thoughts that floated through my mind a few hours into my drive home. I crossed the state line into Wyoming and set the cruise control to 80. Vapors of snow, swirling and ankle-high, danced across the freeway. About 60 miles west of Laramie, things took a hostile turn. The sky dropped and the horizon rushed at me like a cavalry charge in a snowglobe. I had wandered into a whiteout so thick I couldn’t see the hood of my car.

Choking up on the wheel, I threw my hazards on and slowed to about 25 miles per hour. If I went any slower, I worried, I might get rammed from behind. Any faster and I could smash into an invisible truck or slide off the steep banks, which were unprotected by guardrails. The fear of dying alone in the beautiful vastness of Wyoming consumed me. Thankfully I didn’t. After 40 sphincter-clenching minutes, I found myself under a blue and prosperous sky. A combination of prudence and good fortune had guided me through the storm, and I emerged intact.

I thought of the Parkite miners all those years ago, forging blindly into uncertain times with the confidence that things would work out okay in the end. I thought of their progeny, who will do the same in a post-virus world, and maybe even a post-Sundance world.

Later that day, I pulled into Denver right around rush hour. The bumper-to-bumper gridlock was comforting. I’d never felt happier to be stuck in traffic.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.