There’s always been noise in Soho — it’s in the name. London’s famous theatre district is christened after a 17th-century hunting cry (“so ho!”) which once echoed over the now non-existent parkland. When the aristocracy left, hunting cries were replaced by bawdy tunes from pubs and Music Halls, bringing with them the misfit voices of pimps, prostitutes, poets, struggling authors, actors and artists (like Lucien Freud and Francis Bacon). Later, it became a cradle for England’s punk scene, mods, the New Romantics, electro, Carnaby Street fashion, The British Invasion, the city’s LGBT community … you get the point: if it’s going to happen, it happens here.

Yet someone has been turning the volume down. In recent years residents have struggled to hold on to the last independently run institutions thanks to soaring rent, lucrative offers from developers and a wealthier breed of local. It’s a familiar story: If you live in New York, you probably lament the transformation of the Lower East Side; Austin isn’t so weird anymore; the Bay Area is unaffordable to those outside of the tech industry. Under the pandemic, things seem even less hopeful. The last vestiges of old Soho — Trisha’s on Greek Street; The French House, where a patriotic Charles de Gaulle wrote speeches to French revolutionaries, and where Londoners arrive to sample the exotic “half-pint”; Bradley’s, with its Clash and Wham! crammed jukebox; the St. Moritz (run by local legend ‘Sweetie’) — are having to crowdfund to survive. These sites are vital to the area’s spirit, but none are invulnerable, as sadly proven with the closure of Molly Mogg’s and Madame Jojo’s cabaret.

Nobody forgets their first time at Trisha’s. When I lead someone down the stairs of an unmarked black door on Greek Street, their head spins with excitement. An experience like this in 21st century London — all hip coffee shops and Negroni bars — is like ferrying them into the underworld. In a sense, that’s where they’re going, except Bacchus (not Hades) hosts the party.

“If you want to find us, you will,” says Tracy Kawalik, a music journalist who tends the bar, “We’re one of the last little bits of original Soho that’s left. Anthony Bourdain, who was a regular at the bar, called Trisha’s the ‘Dean Martin of drinking establishments’ [when the Parts Unknown star filmed an episode with Marco Pierre White there], and we have decades worth of loyal punters who’d back that up,” she adds. “Trisha’s is more than just a bar. For many, it’s a second home. It’s a place where you can come alone and check out the band, or share a drink with a bunch of wild characters and leave with a whole new set of friends.”

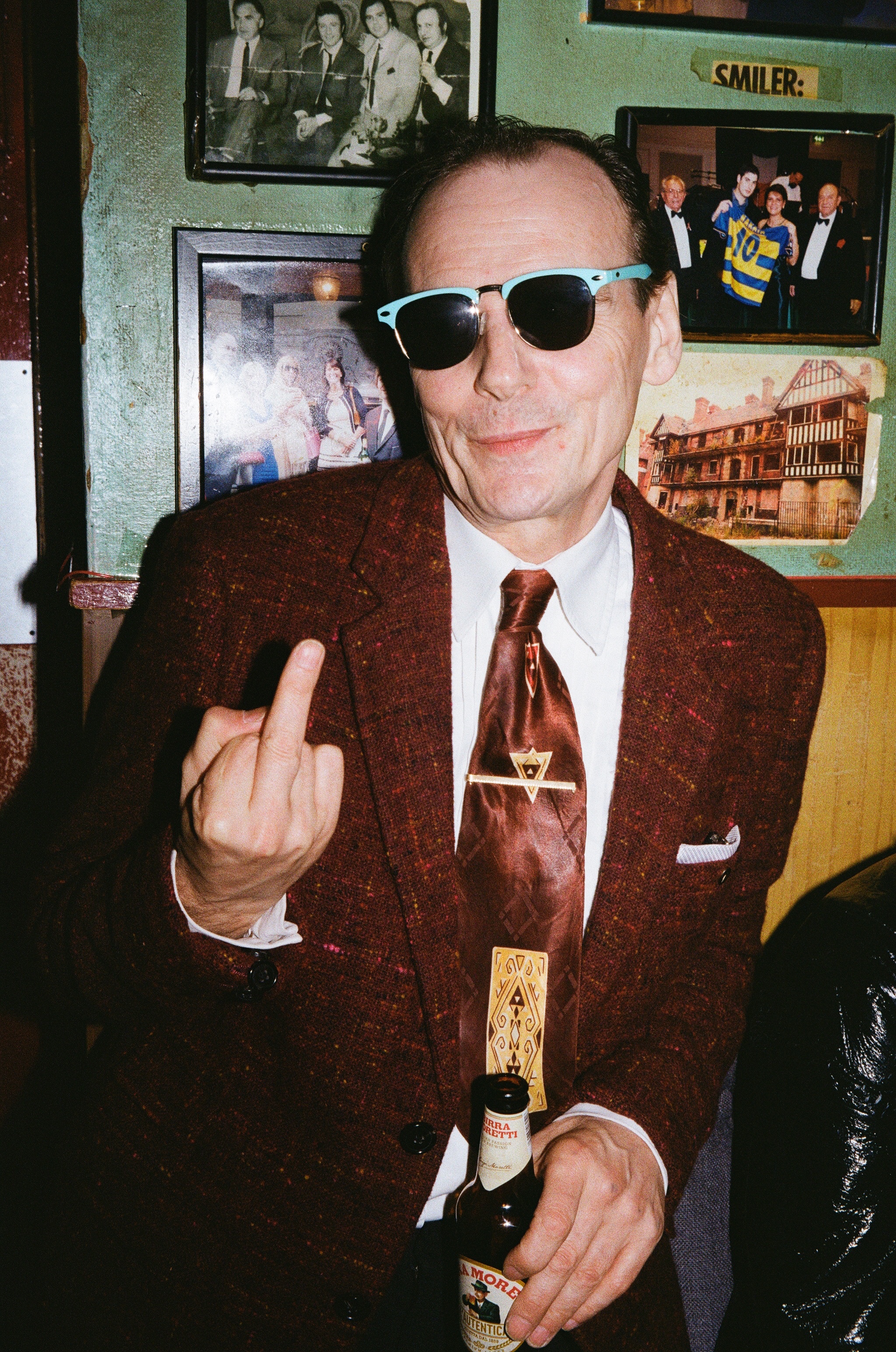

Trisha’s — or “The Hideaway,” or “The New Evaristo” — started as an underground Italian social club 78 years ago, with rumored ties to the mob until Trisha Bergonzi took over. My great-uncle would drop by in the ’60s to play cards, and I’ve been told that the round tables I drink at are likely the same he gambled away my aunt’s grocery money. A large Italian flag, family photographs and Liverpool FC scarves fight for space on the walls. The wine list goes: white, red. Rockabilly or punk pours from a vinyl player, and there is — surprise, surprise — a disco ball. Trisha’s has a reputation as being amongst the city’s most open bars, a place where you are encouraged to mingle with other patrons. But the space is tiny and often crammed, meaning post-COVID laws would restrict capacity to fewer than 10 people. Not only will they pose unthinkable challenges in ensuring everyone stands two meters apart, but they will also take away from the intimacy of places like St. Moritz, Bradley’s and Trisha’s — the one thing that makes these places the hidden gems they are. Tracy reflects: “At Trisha’s, the bartenders shake your hand on the way in, and in my case, kiss your cheek on the way out … No one knows what the future of Soho has in store, but what we do know, is that certainly somewhere like Trisha’s, for now, can’t be the same.”

On the other hand, the longer these bars are not making money, the more difficult it is to resist corporations offering hefty sums of cash for the real estate. The French House spends £15,000 a month on rent (approximately $240,000 per year). Many live week-to-week. If you’re elderly, as most of the proprietors are, it might seem more tempting to take one of these lucrative offers and retire. The aim is for Westminster council to actively protect these sites, recognizing their importance, supporting them with special grants or slowing the influx of hungry developers. Nothing is more heartbreaking than watching a family-run business transform into another Prêt a Manger, or the same old art-deco-themed cocktail bar. Yet, that side is winning the war; they can afford to ride out the pandemic.

Still, there’s hope. Tracy organized a GoFundMe page earlier this month which rapidly exceeded the target. Crowd-funding by Trisha’s, Bradley’s and The French House (follow the links to see how you can donate, and be sure to visit on your next trip to London) have succeeded in rallying urgent support during the lockdown. But with no clear end in sight, how long can they survive on fundraising alone?

As with New York’s disappearing dive bars, more effort must be made to support these establishments during the pandemic. “The response we’ve had from the fundraiser has been incredibly touching, and maybe that’s a sign you know? Maybe the risk of losing your favourite bar, or seeing it replaced by a shitty cocktail joint like London Cocktail Club or noodle chain, is a positive reminder not to take it for granted during isolation.” She pauses. “I’m optimistic.”

There’s always been noise in Soho. Today, the streets reside under a silence so harsh it feels like they’ve been cursed. But whatever challenges the area faces, it sees them off time and time again. Soho (to paraphrase one of its favorite sons) will not go quietly into that good night.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.