We stood on the bow of the ship, scanning the cloudy horizon for a speck of black. Suddenly, a shout of “whale!” pierced the silence. A spout of water shot into the sky, signifying a humpback purging the salty Pacific seawater from its blowhole. Captain Matt Whelan steered the boat toward the massive mammals as we prepared our cameras. For the next hour, we clicked away as humpback after humpback leapt upward in the air, like an aquatic, 35-ton LeBron James, before splashing back down into the ocean.

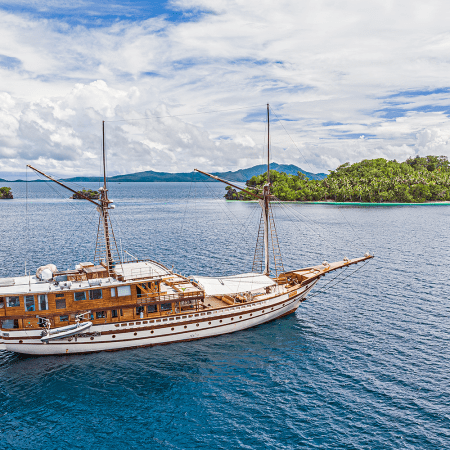

It almost felt as if the whales were putting on a show for me and the seven other passengers aboard the MV Swell, a 110-year-old, 88-foot tugboat that’s been transformed into a plush, 12-passenger ship. This may be the only former tugboat in existence with a hot tub and gourmet kitchen.

Cruising Alaska has been a popular activity for decades, arguably since 1899, when wealthy railroad magnate Edward H. Harriman hired a steamboat and brought along a group of scientists and ecologists like John Muir up Alaska’s famed Inside Passage, before heading further north toward the Arctic Circle. The Passage is protected as part of Tongass National Forest, the largest intact temperate rainforest in the world and home to incredible wildlife, like humpbacks, orcas, bald eagles and brown bears.

Today, most visitors opt for a massive cruise ship, where the surrounding wilderness can seem secondary to shuffleboard games or catching a movie inside the onboard theater. But when my friend, Maple Leaf Adventure’s Maureen Gordon, invited me to tag along on a 10-day voyage up the Inside Passage, I was warned it would be a different type of adventure, filled with nearly nonstop wildlife and hours spent hiking Tongass’ dense, old-growth forests.

After a day exploring the city of Ketchikan, the next morning we chugged out of port, listening to the roars from the massive Carnival ship fade into whispers, then silence. Because of the Swell’s relatively small size, we were able to both reach areas the larger cruise ships couldn’t access, as well as be much more flexible in our itinerary. If we saw whales in the distance, we could almost instantly change course. If we wanted to watch brown bears from the relative safety of kayaks, we could. If one of my fellow passengers had a request, Whelan would do whatever he could to fulfill it.

Complicating matters would be the realities of sea travel. Nearly every decision Whelan made would be with the tide window in mind. The width of the Wrangell Narrows and other straits can dwindle down to about the length of a football field, and the shallow depth meant we sometimes had to wait for the tide to rise and the current to flow in the right direction.

My cabin was paneled with lacquered pine, with a small dresser standing at the end of the double bed next to the snug private bathroom. A tiny closet lined with shelves didn’t have room to hang up any clothes, but passengers typically aren’t dressing for fancy dinners or nights dancing in the nonexistent onboard disco. I wouldn’t go as far as saying the rooms were lavish, but they were definitely comfortable. But for someone who spends about half the year living in a camper van, it felt like the Ritz Carlton.

While our personal accommodations were a bit sparse, the overall experience was definitely lavish. We often gathered in the similarly wood-paneled salon, where we ate and spent hours thumbing through books and maps of the area. Our first night’s dinner of salmon, asparagus and black lentils was a harbinger of excellent meals to come. Chef Mary Savage created three mouth-watering meals a day, relying heavily on fresh-caught Alaskan seafood. At the end of dinner each evening, Whelan would detail the next day’s adventure.

How to Plan a Trip to Antarctica

Everything you need to know ahead of your first trek to the White ContinentIt was a multinational group of passengers — two Swiss, three Germans and an American couple — with a mostly Canadian, five-person crew. I remember enough high-school German to comfortably converse with a two year old, assuming the two year old spoke slowly and didn’t use any big words. Luckily all five of the German-speaking passengers spoke excellent English, perhaps even better than my own.

At night, small groups would either congregate in the hot tub or elsewhere on deck, watching the sun finally disappear behind the Coast mountains, casting the sky in deep purple, then black. On sleepless nights, I’d walk out on the deck to stare at the impossibly bright Milky Way and stars.

Anchoring just off Admiralty Island National Monument, a few of us paddled kayaks closer to shore, hoping to see one of the more than 1,600 brown bears that call the island home. It’s the largest concentration of coastal grizzlies in the entire world, so we felt pretty good about our chances. Luckily, we quickly got our wish. A subadult bear exited the woods and ambled across the rocky coastline, overturning the occasional rock looking for food. She seemed nonplussed by our presence, so we followed from a safe and respectful distance, but were still able to hear the sounds of her long claws scraping against the smooth beach stones.

We followed for a few hundred yards, where the bear found a tide pool filled with salmon caught unaware of the low tide. For the next 20 minutes, we watched the bear scamper through the water, trying to catch and eat as many fish as she could. She looked like she was having a grand time, as were we. We could have spent an entire day watching her, but we needed to return to the boat so other passengers could take their turn.

That wouldn’t be our last bear encounter however. The next day, we traveled further up the island to the Pack Creek Bear Viewing Area, operated by the US Forest Service. During the spring and summer, only 24 permits are issued to visitors daily, but we managed to snag enough for our group. Watching at an observation post near the bay, we saw nearly a dozen bears, including a mama and two cubs keeping their distance from larger, possibly aggressive male bears. We felt safe on the two viewing platforms, but that charge of danger still electrified the air, especially when walking between the two through the thick forest, where we imagined a bear hiding behind every spruce or hemlock, waiting to give chase.

While we didn’t see many large cruise ships, smaller fishing vessels were a frequent sight. Dwindling fish populations and warmer ocean water means fishermen must travel further and further north to catch their prey. But what happens when there’s no more north to travel?

As we neared Sawyer Glacier, the water changed from a greenish aqua to a darker hue; it was as if a child ran out of one color of Crayolas and decided to just continue on with another. The glacier has retreated several miles since Muir’s time, giving us the day’s first reminder about the effects of manmade climate change in this vast wilderness. Seeing the growing number of ice chunks floating in the water, I chuckled at a bit of trivia we learned earlier in the trip: the Swell was built in 1912, the same year as the Titanic. If we hit an iceberg this day, no one was going to keep me off the door.

The chill from the glacier had us busting out wool hats and warm jackets in early August. I silently cursed myselft for neglecting to bring the thermal gear we bought specifically for this trip.

Taking a zodiac to get closer to the glacier, we got our second reminder. Calving — when ice sheets topple off the glacier — isn’t unusual for the summer months, but the rate at which it was happening was both unnatural and unnerving. A huge thunderclap would erupt through the canyon, followed a few seconds later by huge chunks of ice tumbling down into the water below. The louder the crack, the more ice fell. It was both an incredible feat of nature and a terrifying hint at our future. One particularly large chunk had our guides piloting our zodiacs away before the ensuing wave could potentially cause our boat to capsize.

Back aboard, we make our way to our next destination. The problem with trips like this is nothing is guaranteed. After lucking out with so many whale sightings early in the trip, passengers would get restless when we didn’t see any orcas or humpbacks, stalking about the decks and ribbing Whelan with some good-natured teasing. When we finally spot a plume, the sense of relief from both the crew and passengers is palpable.

Our final destination was the Baranof Warm Springs just south of Sitka, a popular day trip destination for locals. From the dock, it was perhaps a 15-minute hike to reach the bubbling pools. It was a little odd running into other people after being surrounded by the same folks for more than a week, and it reminded us the trip would soon end. The hot water felt glorious to my aching muscles, even if I did smell faintly like sulfur for the next couple of days.

Even though we spent nearly 10 days aboard the small tugboat, I didn’t want to stop at Sitka; rather, I wished to continue on like Harriman and Muir. There was still so much more of Alaska I wanted to see. However, not knowing current laws about mutiny and/or piracy, I decided to disembark with the rest of the passengers. Alaska will still be there when I return

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.