Michael Jordan is the most famous athlete of my lifetime, a billionaire global superstar who during his playing career became the universal standard for nigh-psychotic competitiveness, and whose face, logo and likeness have been stamped onto shoes, steakhouses, jerseys, knives, basketballs, trading cards, posters, figurines and just about any type of tchotchke you can imagine. (No sex toys, though — I checked.) He’s so famous that there was once a time when that fame was signified by his absence, instead of his ubiquity.

Back in that bygone era of “the mid-’90s,” Jordan was absent from every licensed basketball video game sold in stores. The reasons why are boring — something about the fee for licensing his image — and I will not dissect them. But because these games could not use the actual Jordan, every digital Bulls team instead included “Guard Bulls” or “Player 99,” a generic, faceless shooting guard who stood at an identical 6’6 and bore nearly perfect attributes meant to mimic his as closely as possible. As one of the millions of kids trying to play with his favorite player on his favorite team, my brain had to meet the game more than halfway in imagining that I was controlling a mini-Jordan on the court. But when Jordan was at the peak of his global fame, he could force his fans to perform this mental work; sports culture followed him around willfully, a perk of being one of the coolest and successful people alive.

Alas, despite being the greatest basketball player ever, even Michael Jordan couldn’t overcome the fact that we age forwards, not backwards. Today, someone born in 1998, the year he won his final title with the Bulls, is old enough to petulantly scoff “Seriously?” when asked for an ID at the bar. Jordan is still one of the most famous athletes in the world, but there are millions of people who might not even remember exactly why he’s so famous — who recognize him more as a meme, whether because of his tears or the lamentable cut of his pants.

When you hear him speak today, Jordan follows the typical playbook for retired athletes looking to recapture their glory, insisting that sports today aren’t shit compared to back in the day. But like the Beatles or Catholicism, his mere existence demands a different standard of evergreen recognition. The latest pair of sneakers bearing his silhouette, which are released nearly every week, remain day-one must-haves, and his retro Air Jordans find new life in different colorways almost as often. A decade ago, he even consented to having his career form the backbone of NBA 2K11, where players were allowed to control Jordan himself, not Guard Bulls or Player 99, to recreate several of his career highlights.

Lately, this reputational maintenance has manifested as The Last Dance, a 10-part documentary recapping that final season with the Bulls. The Last Dance, which debuted on Sunday night and will continue for the next four weeks, draws on reams of archival footage shot by a camera crew that followed Jordan and the Bulls as they embarked on their last and perhaps most impressive championship run throughout 1997 and ‘98. For years, that footage sat unused as Jordan continually rebuffed all offers to transform it into a formal documentary. It wasn’t until 2016, when LeBron James — now commonly regarded by men who like to debate things as Jordan’s only true competition in the basketball GOAT conversation — won his third championship by bringing back his Cleveland Cavaliers from a historic 3-1 deficit against the Golden State Warriors (who themselves had set a 73-9 record in the regular season and broken a mark set by Jordan’s Bulls), that he finally relented.

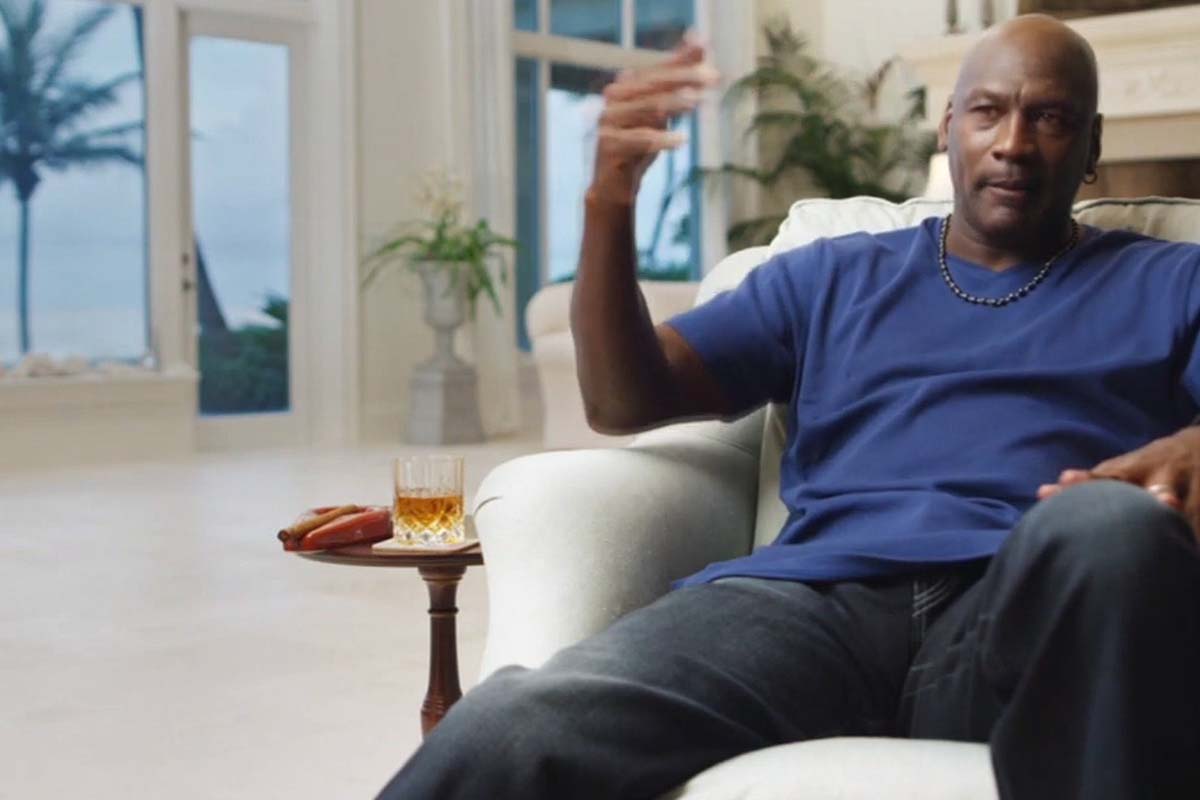

The Last Dance was originally set to premiere in June, following this year’s NBA Finals, where it’s entirely plausible that James could have won his fourth championship and set off another interminable round of GOAT debates. Due to the fact that live sports no longer exist, and may not for months to come, the series’ release date was pushed up to April, after the filmmakers worked overtime to finish what they had. As a result, while the documentary was always going to bring in big numbers, it became somewhat of an event in the days leading up to Sunday, with release partner ESPN producing seemingly dozens of ancillary articles about Jordan using resources that may have normally gone into Finals reporting. For the first time in weeks, millions of people — or, at least, sports fans — were allowed to uniformly shift their focus onto something that isn’t even tangentially related to COVID-19. While I’m sure everyone involved is very sympathetic to the ongoing conditions created by the coronavirus crisis, I’m also confident that a small part of Jordan is thrilled by the change in circumstances, since they’ve provided him a rapt audience with the attention span to revisit his entire existence, culminating with the titular season that was arguably his greatest achievement.

The series opens with interviews and flashbacks contextualizing the stakes. The year was 1997. The Bulls had just won their fifth championship of the decade. They were a world-spanning phenomenon, and yet it was all at risk of falling apart due to ongoing strife within the organization. Jordan had said he wouldn’t play for anyone but coach Phil Jackson, and before the season, then-Bulls general manager Jerry Krause publicly stated this would be Jackson’s last. Hence the title of the documentary, which Jackson declared the theme of the season at its start. They were physically broken down and psychically beset upon by society, and so on and so forth, but despite the overwhelming odds they catapulted themselves to victory through sheer will and utter gumption and whatever else goes into a Gatorade commercial.

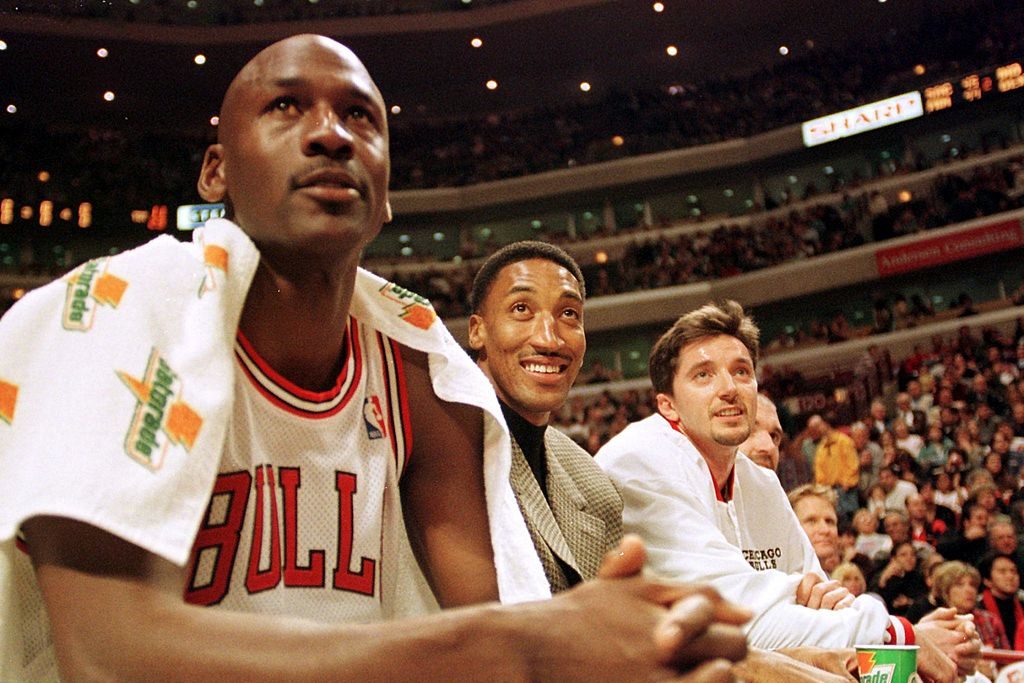

All of this is accentuated with glorious footage of Jordan wearing berets and warm-up tracksuits as he strolls through Paris, and cavernous testimony from Pippen, Jackson, Dennis Rodman and other figures of the era. Everything is sucked into the orbit of how much these Bulls mattered — even former president Barack Obama is cheekily credited as “former Chicago resident,” a nice gag but also more or less just what he was during this halcyon period. (He’d just been elected to the State Senate in 1997, but at the time only committed citizens and total nerds knew this.)

And then … it pivots. Suddenly, we’re back in the early ‘80s, learning about Jordan’s childhood and career at the University of North Carolina. When we jump back to 1997 to learn about how he prepared for the final season, it’s not long before we cut back to the start of his career, and how he helped revive a moribund Bulls franchise, how he blazed through the NBA in his rookie season, how he put up a ridiculous 63 points against a loaded Boston Celtics team in his sophomore campaign and became quickly anointed as the greatest basketball player alive.

Much of this has been chronicled before, making its presence somewhat draining. The core promise of The Last Dance is all this never-before-seen footage, but the series assumes that Jordan’s entire career is never-before-seen, rather than one of the most documented careers in all of sports. It’s cool as hell that Larry Bird remarked “that’s God disguised as Michael Jordan” after that 63-point game; I’ve also heard that quote repeated in the millions of times, and I’ve seen Larry Bird talk about it from the present in the thousands. Faced with the reality that basketball fans today might not know enough about him, Jordan didn’t just open up this last year with the Bulls to scrutiny — he presented his whole life story for retelling, which is why The Last Dance will be an inconceivable 10 episodes, or about how long it took Ken Burns to teach us about the Civil War.

Those episodes will fly by, because Jordan’s career was a delight, and given the particular circumstances, talking heads talking shit about the old days is a wonderful distraction. But it does highlight the demands of his ego, that Jordan only gave his consent knowing that the everyday footage of the team during that final campaign — every frame of which is interesting and worth watching, because it shows the then-coolest person in the world in a series of casual environments, which is not a setting where we often get to see the coolest person in the world — would be nestled into a more conventional story that’s already been told dozens of times already. Many of us are stuck in our apartments, quarantined, desperate for some semblance of regular society. Communal TV-watching, more than Zoom yoga or recipe chain emails, counts. And right now, learning how tight Michael Jordan was is the closest we’re going to get. It’s a hell of a boon for Jordan, given his obvious fears of being left in basketball’s past, and it’s already become ESPN’s highest-rated documentary ever.

Fortunately, there is much more to learn about in this documentary. The second episode delved into Scottie Pippen’s hardscrabble background, and the third episode will get into everything about Dennis Rodman. And I maintain belief that the rest of the archival footage from the last season will be awesome, because it purports to show Jordan at his competitive worst, shit-talking teammates when they weren’t as good as him, and just being a straight-up miserable asshole to Jerry Krause (who, by the way, is literally dead and can’t defend himself). Jordan has even laid the groundwork for an apology tour, noting that this footage may make him seem like a horrible guy. This is PR, obviously. Good or bad, he must be thrilled we’re all paying attention.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.