One night shortly after the 1989 NCAA men’s basketball title game, a game in which referee John Clougherty called a blocking foul on Seton Hall’s Gerald Greene with three seconds left in overtime, thus enabling Michigan’s Rumeal Robinson to sink the game-tying and then -winning free throws, Pookey Wigington, a reserve guard for the Pirates, wasn’t thinking about the stinging loss, or the three minutes he played during the Final Four. He was trying to figure out why a guy had just run up on him on a New York City sidewalk and demanded a jersey.

“I appreciated that he said I was one of his favorite players,” Wigington recalls, but thought it odd when the stranger first “told [him] that he’d bust my ass” in basketball and then asked “to get him one of my jerseys.” Notwithstanding the strange request, there was nothing the senior guard could do. “I couldn’t even keep my own jersey.” The encounter ended after about a minute or so, but not before Wigington was given a phone number, just in case he ever came across a spare number-4 royal blue-and-white uniform. Wigington forgot about that meeting until a few years later, when a friend called and told him to immediately turn on MTV. Phife Dawg from A Tribe Called Quest was wearing Wigington’s jersey.

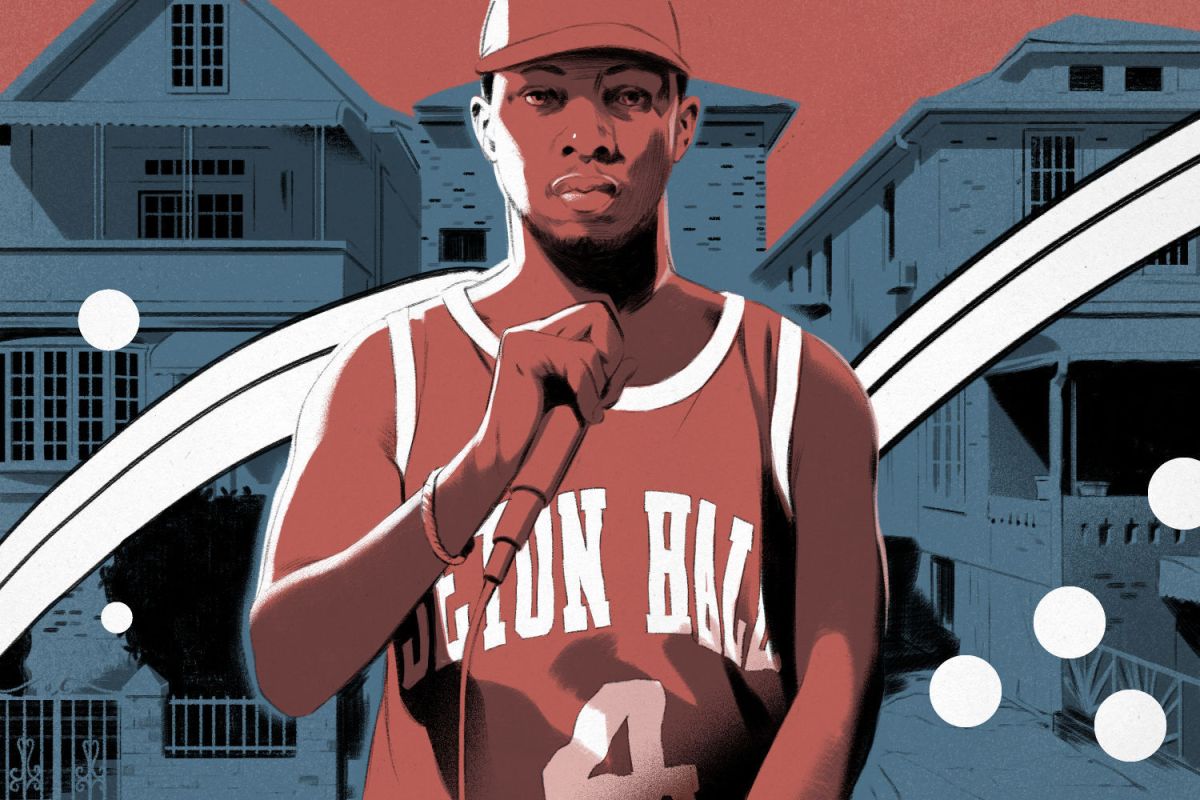

When Phife Dawg — né Malik Taylor — passed away in 2016 from complications of a decades-long struggle with diabetes, the majority of his obituaries focused on his role in the founding of ATCQ, one of hip-hop’s seminal groups, as well as his dexterously winking lyricism (“You got BBD all on your bedroom wall/But I’m above the rim and this is how I ball”). Also prominently mentioned in those obits was Phife’s obsession with sports — and in particular, his jersey collection. On the liner notes from the group’s debut album, People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm, Phife rocks a New York Knicks Starter jacket; in the music video for the album’s single, “Can I Kick It?”, he sports an Atlanta Braves jersey with a Georgia Tech hat (a nod to Kenny Anderson, a fellow Queens native and high-profile Ramblin’ Wreck basketball player). And in the video for “Check the Rhime,” the lead single from ATCQ’s second — and widely influential — record, The Low-End Theory, Phife not only wore a Cleveland Indians jersey, he also donned Wigington’s jersey.

“We were the darlings” of the city, says Wigington. “Phife followed the game, and knew who I was. He was one of the guys that saw himself in me, playing at a high level.” But why Wigington’s jersey, rather than one from Terry Dehere, John Morton or Andrew Gaze, the stars of that Pirates’s squad? As the self-proclaimed “five-foot assassin,” Phife alludes to his rationale in an early bar: “I’m just a fly emcee who’s 5-foot-3 and very brave.” Wigington also stands 5-foot-3, and remains the smallest player to ever suit up for a Big East team. “It’s like me with Spud [Webb] or Muggsy [Bogues],” explains Wigington. “When I saw those guys, I truly respected them — I knew the work, I knew the plight, and I knew what they had to do to be where they were.”

Before speaking with Wigington several months ago, I had watched the “Check the Rhime” video countless times since it first aired in 1991. Along with “Scenario,” the third single on The Low End Theory, it is my favorite video in the group’s videography. The camera alternates between shots of Phife, fellow MC Q-Tip and Ali Shaheed Muhammad (the group’s DJ and co-producer) in their childhood neighborhood of St. Albans, Queens, as well as a raucous, shut-down-the street performance atop Nu-Clear Drive-In Cleaners on “the boulevard of Linden.” Other than the video’s vivid color scheme (which, according to director Jim Swaffield, was a by-product of the color solarized effect that, as Q-Tip said, “sizzles the retina”) and groundbreaking use of green screen, I was always drawn to Phife’s Seton Hall jersey. Why would he pick such a random jersey?

The video was somewhat a debut for Phife’s sartorial evolution. During the group’s earlier videos, as he said in a 2014 interview, “I used to hate what we used to wear.” (Case in point: for the “Bonita Applebum” video, Phife rocked a puka shell necklace with overalls.) But starting with the “Can I Kick It?” video, Phife began to showcase his sports-obsessed fashion sense. Swaffield says the budget for “Check the Rhime” was minimal, and Phife “wore what he felt like wearing,” adding that the three-day shoot coincided with a July NYC heat wave in which temperatures reached 107 degrees.

But Wigington is a sui generis and obscure choice, even for someone with Phife’s sports pedigree — the jersey of a guard who, after three surgeries, had no cartilage in his right knee and averaged a scant nine minutes during his two college seasons is hardly a collector’s item. “You’re going to find a Dehere or Morton jersey before you find mine,” Wigington says, laughing. “He had to search for mine.” It’s truly a deep cut for the lead music video that would launch the group into the musical stratosphere, and that’s why Phife’s choice had puzzled me for years.

I’m not the only one flummoxed by it. Rob Markman, a rapper and former head of artist relations at Genius, remembers “bugging [his] parents for a Seton Hall jersey after Phife wore it in the ‘Check The Rhime’ video”; in a 2016 Uproxx article, the jersey is mentioned as “one of music’s greatest mysteries” (as well as potentially the first instance of a basketball jersey in a rap video). And as Big Pun raps in the 2004 track “Bring Em Back,” “I’m from the X, and I’ve seen it all/Shorties with dreams of playing ball for Seton Hall.”

While Wigington had seen his jersey plenty of times as an undergrad — “people were bootlegging them down in Newark” — they were clearly replicas: “My name was always spelled wrong.” So was Phife’s a fake as well? The rapper claimed that he would never purchase a replica, telling an interviewer, “My jerseys had to be authentic, [because] if you was rocking a replica, you was playing yourself … you couldn’t do that. I needed the stitching.” According to Dion Liverpool, Phife’s manager for the final two decades of his life, the rapper had relationships with apparel shops up and down the East Coast, but mainly patronized Philadelphia’s Mitchell and Ness and “this shop in Buckhead, in Atlanta, that’s not open anymore.”

“He didn’t care what he spent on a jersey,” says Liverpool, adding, “he’d buy a jersey based on a person’s career, rather than the jersey having an interesting colorway.”

But as to the authenticity of Phife’s Wigington jersey, the ex-guard isn’t certain. “I don’t remember [Seton Hall] having a bunch of jerseys, but he could have gotten it from them,” says Wigington. “His jersey is a bit different than what I wore, but I can’t tell.” Indeed, the capitalized block font used for Seton Hall doesn’t mesh with the team’s flowing cursive used at that time — though the piping around the neckline is two-toned in light blue and white, which was a hallmark of the 1989 team.

Several of that team’s managers claim there was little chance a former colleague slipped the jersey to Phife for cash or any ATCQ perks. After that title-game loss, manager David Flood was walking out of Seattle’s Kingdome and, after striking up a conversation with a fan, showed him the Final Four ring he had just been given. He was offered $5,000 on the spot. “But Coach [PJ Carlesimo] was good to the staff and the team,” explains Flood (though he admits to “hesitating for a second” before declining to sell his ring). Anthony Chaves, a sophomore manager on the team, is far more blunt: “PJ did not mess around. That dude is all business, and he’d let you know in a second if you stepped out of line.”

Chaves continues, “I’d get random requests from friends to give them a jersey, or some other apparel, and I’d say, ‘Hell no. Do you know our coach?’ He would literally kill us.” (Prior to Seton Hall’s national semifinal game against Duke, in which the Pirates rallied from 18 points down to win by double digits, Chaves remembers seeing a player’s-only jacket in the crowd. His first thought? “How the hell did [they] get that thing? Please, I hope [Carlesimo] doesn’t see it.”)

Neither Flood nor Chaves could verify the origins of Phife’s jersey. The latter believed it could have been a back-up jersey, as those never listed a player’s name and used block font — but Felix Roman, a freshman student manager who later helped scout international competition for Chuck Daly in advance of the 1992 Olympics, is definitive: there is no way Phife’s jersey was real. “It’s not the same material,” he says. But how do you know that? “I collected and then washed those uniforms after practice and games for four straight years,” Roman clarifies. And in the NCAA and Big East tournaments, “I was the only one who did the laundry, to make sure no one stole anything. I was trusting nobody.”

So if Phife didn’t have an inside connection, is it possible he copped an authentic Wigington jersey through a retailer? That would have been an even more challenging task, claims Matt Wintner, who was a marketing coordinator at Apex One in the early 1990s. A leading sports apparel company, Apex One’s annual revenues was upwards of $100 million, and before it was acquired by Converse in 1995, it was the sole licensee of the Dallas Cowboys. But what separated Apex One from Starter, Nike and other sportswear companies was the college market. No other company devoted as much energy into outfitting the top college football and basketball programs. “It was totally the wild West,” Wintner says.

Though the market existed in the 1980s, it didn’t boom until the emergence of Michigan’s Fab Five in 1991-92. Before, says Wintner, “you’d have to call an equipment manager to ask who manufactured the jerseys, and then call the manufacturer to ask if they had any blanks to sell.” Which is why there were no authentic Patrick Ewing jerseys during peak Hoya Hysteria.

Apex One signed more than a dozen schools, ranging from Arkansas and Kentucky (Wintner says the company’s contract with Rick Pitino topped $2 million for three years) to Manhattan and BYU. After outfitting the players and coaching staff, Apex One would then sell a limited amount of authentics and a much larger batch of replicas through regional locations of retailers like JC Penney and Foot Locker to “recoup some of the money we laid out” (specifically, for mock-ups — like the $175 the company spent making a limited authentic Arkansas football jersey for President Bill Clinton — and salesman samples).

The two jerseys “were made to look as close as possible to each other,” but even then, to get a jersey from a lesser player like Wigington, Phife would have needed an in, says Wintner, “to know someone to give that up.” He explains that when Apex One began working with the Razorbacks, the only jersey manufactured was Corliss Williamson’s — without the name on the jersey. “It was a number 34 jersey, so consumers knew to associate it with Williamson,” Wintner adds. Even diehards might not immediately know number 10 was Todd Day’s number, a player who averaged 23 points per game his senior year before being selected in the lottery of the 1992 NBA draft — which is why Apex One never even thought to manufacture Day’s jersey for retailers. According to Wintner, Phife’s jersey, then, had to be a by-product of someone “coming as close as possible to replicating the authentic” Seton Hall uniform.

In an interview before he passed, Phife confirmed the first authentic jerseys he ever purchased included a Larry Johnson Charlotte Hornets jersey and “a couple others.” But the UNLV big man was drafted in June 1991, just a month before Swaffield began filming “Check the Rhime.” It seems far-fetched that the rapper would have secured his apparel haul so close to the video shoot. Despite the two-toned neckline, seemingly a clue that Phife had an inside source, it’s likely the Wigington jersey was indeed a replica.

To Anthony Gilbert, though, any questions of legitimacy really don’t matter, and shouldn’t diminish what that jersey meant for Phife’s overall legacy. “The more obscure the jersey, the team, or the colorway, the more street credibility you have,” says Gilbert, a longtime basketball writer and frequent collector. “What Phife did was an OG move — for him to go out of his way to pay to get it made, or someone handed it off, whatever real story is, he gets all the respect in the world.”

Wigington lost Phife’s phone number shortly after that initial meeting, and while he bumped into Phife just one other time “in passing somewhere,” who is now the president of the television and film production company HartBeat Productions (and business manager for Kevin Hart), says he watched that video “at least 1,000 times.”

“I went crazy. That dude was a real fan of the game.”

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.