It was a haircut that introduced Matt Hranek to the world of Japanese men’s magazines.

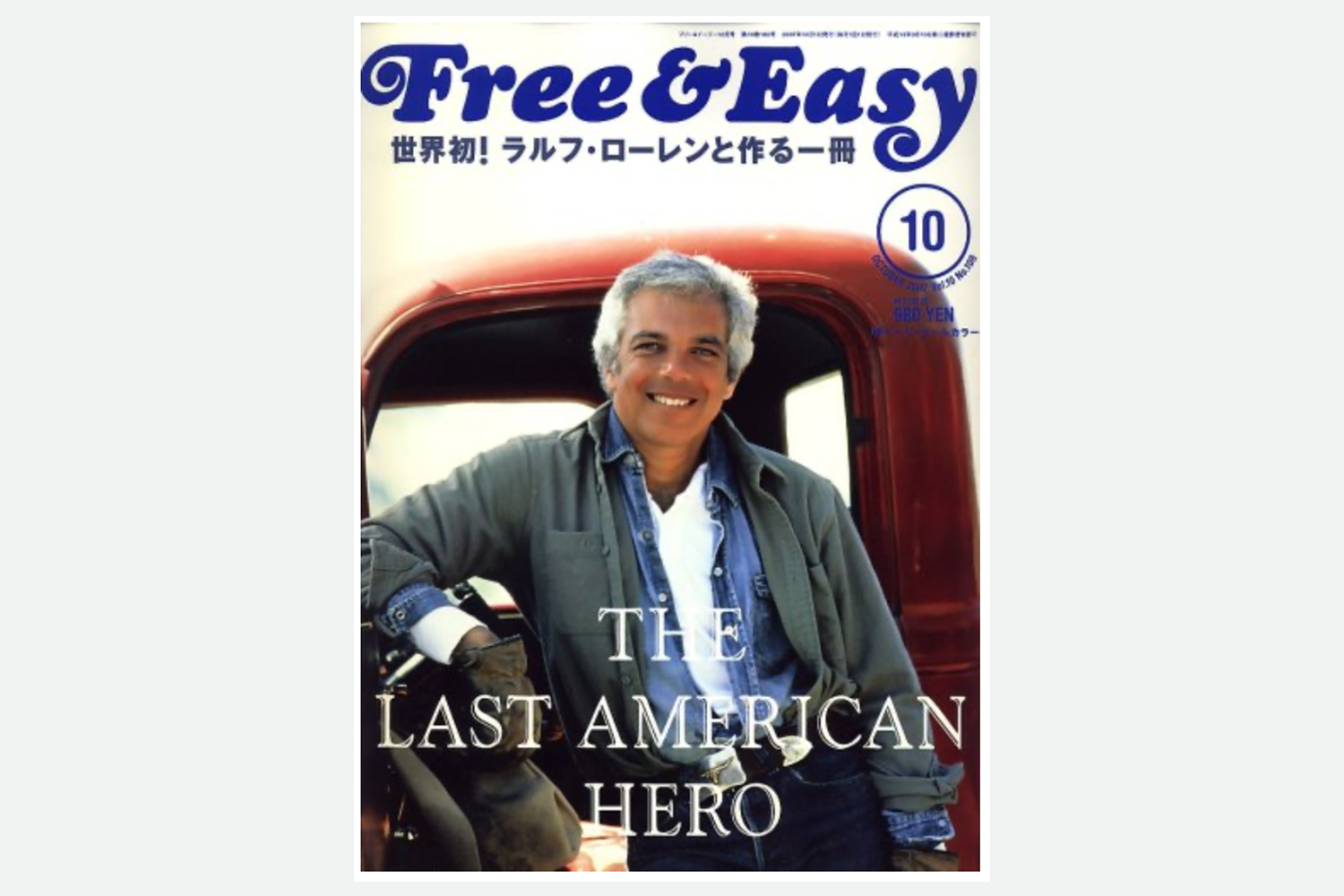

While waiting to have his ears lowered at Freemans Barbershop circa 2008, the author and photographer found himself leafing through thick, Americana-obsessed tomes like Free & Easy, which captured his interest and imagination with nary a word of English.

“The first thing I thought was so interesting was that it wasn’t a fashion magazine,” Hranek says. “They were talking about real style, and real personal style … I didn’t even need to speak Japanese or read Japanese. I just thought that visually it was so well approached in a very minimal but thoughtful, environmental way, and I was really inspired by that.”

Hranek was soon making pilgrimages to Kinokuniya, the Japanese bookstore by Bryant Park, to delve deeper into the catalogue. He cities Japanese men’s magazines as an influence on his own publication, WM Brown, which launched in fall 2018 and shares a similar affinity for street style photography and simple laydown shots of vintage clothing and gear.

“I dug that whole approach and was doing that myself at the time. There were a lot of American magazines that weren’t interested in that,” he says.

W. David Marx, the Tokyo-based author of Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style, dates the rising American interest in Japanese men’s magazines to the same time as Hranek’s epiphany.

“This started in the Great Menswear Boom of 2008,” Marx tells InsideHook. “A lot of the information men looked for was only available in these magazines. A lot of bloggers went to Kinokuniya, bought issues of Free & Easy, etc. and scanned the pages for content.”

In a pre-Instagram world, the highly visual nature of the magazines — a Free & Easy feature on boots could include more than 100 pairs photographed over 16 pages — made them a valuable reference for even non-Japanese speakers.

“Japanese men’s magazines stand out compared to most American men’s magazines not just because of their depth of knowledge, but their unique ‘catalog’ format,” Marx says.

“Whereas American men’s magazines have always mixed fashion advice with short stories, celebrity interviews and a lot of writing, Japanese men’s magazines are very visual and product focused. They are called ‘catalogue magazines’ because they show dozens and dozens of products on each page, including price and where to buy. In an increasingly consumerist world where people want to see new products expertly selected and learn how to correctly style them, Japanese magazines appeal even to people who can’t read the explanatory text.”

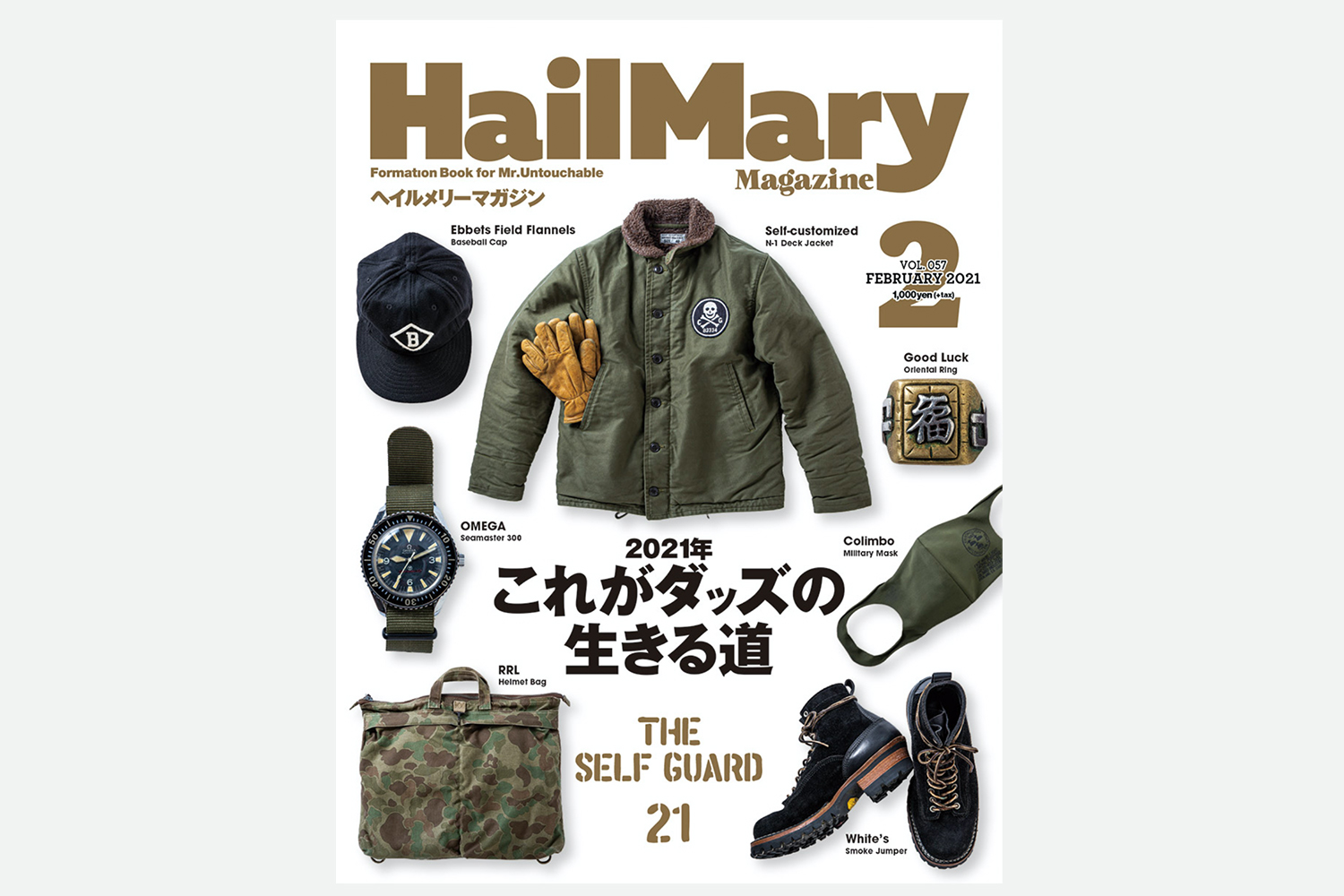

And yet there are occasional pops of English that can prove humorously perplexing, like captions under stylish subjects (examples: “Mr. Strong Boy,” “Mr. Rugged Photographer”) or the title of a popular recurring Free & Easy feature called “Dad’s Style,” a tradition that has continued with its successor magazine, Hail Mary.

Aya Komboo, a Tokyo-based journalist with over a decade of experience contributing from the United States and Europe to titles like Free & Easy and Hail Mary, found herself explaining to confused American subjects who were bachelors or without children that paternity was not a “Dad’s Style” prerequisite.

“According to the editor, the ‘Dad’ was defined as a man who established a professional career and a unique lifestyle while holding enthusiasms about culture, fashion, hobbies and other intellectual items,” Komboo says.

Another often-used English phrase across Free & Easy and Hail Mary is “Rugged Style,” which Komboo says her editor defined as “unaffected, sincere, tough and manly. Men with this style like outdoor activities and enjoy a wide variety of fashion, including workwear and even military uniforms.”

And while the text is foreign, many of the subjects have proven intimately familiar to American readers thanks to the long-standing Japanese interest and even nostalgia for Americana.

“Readers seem to miss the good old days in America and still have good memories of American actors including Steve McQueen and movies including Easy Rider,” says Komboo. “They see American spirits in Ralph Lauren, RRL, J. Crew and Brooks Brothers, as well as in vintage jeans, and miss their own youth days strongly influenced by American culture.”

When Komboo began her career at the turn of the millennium, the Japanese magazine industry was in the midst of a boom, with titles launched on a near weekly basis. More recently, the industry has felt the same squeeze as its American counterpart, and many titles have been pushed into bankruptcy or gone online-only. Free & Easy itself ceased publication in 2016, though Komboo explains that this was the result of an amicable split between the magazine’s business side, which operated two specialty stores and a clothing brand, and its editorial side, which left to create Hail Mary under founding Free & Easy editor Minoru Onozato.

Though the industry has contracted, it’s still rich in titles: Komboo is quick to list over a dozen that remain prominent in the market, including Men’s Club, Brutus, Popeye, Oceans and Lightning. Komboo believes the comparative resilience of Japanese magazines is due to their more diverse and targeted nature, where titles cater to specific niches and are often sold at bookstores and cafes rather than by subscription.

“Big companies dominate the US publishing market, while many small companies in Japan keep specific market segments — small, but enough for them to survive. Unlike mass media dependent on the general public, such small companies are trying to meet the needs of only small groups of people who have special interests which their U.S. counterparts may otherwise ignore,” she says.

Among American readers today, Marx says that Popeye continues to be popular thanks to the younger focus and active Instagram presence of the self-described “Magazine for City Boys,” and workwear-focused Clutch has earned a cult following among denim heads and boot enthusiasts. Marx also says there is an “extremely niche” but “passionate” market for vintage Japanese men’s magazines in the U.S., U.K. and Australia, which he participates in via his “Ametora Book Store” hosted on Instagram and at The Armoury.

And for some, being featured in a Japanese men’s magazine continues to be a greater honor that an appearance in a stateside equivalent. Such a view is held by Hranek, who eventually found himself the subject of several profiles.

“I just felt like, ‘Now I’ve made it,” he says. “That was far more important to me than a profile in GQ or Esquire.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.