Jordan came back. So did Brady, Lance and Phelps. Tiger’s never officially retired, but has staged multiple comebacks from retirement-worthy incidents. Usain Bolt floated the idea of un-retiring in a video this spring. Kelly Slater was supposed to be wrapped up by 2019, but is still competing at age 50. Tony Hawk came in fourth in an event at the X Games last year, 18 years after he said goodbye to professional skating. Yesterday, Serena Williams acknowledged in an appearance on Good Morning America that she’s already reconsidering her decision to leave the game of tennis.

Retirement is hard. We like to visualize it as a passive state of bliss: eighteen holes and mojitos, on an endless loop. But in reality, it’s an active commitment, a decision that must be made every day, in service of moving on, finding peace, courting new challenges, sourcing new springs of creativity.

Among the larger population — and even among other athletes — elite athletes maintain a peculiar relationship to retirement. They retire around age 40. We consider them very old (and all the more excellent) for having performed so well in the league for so long. They typically have hundreds of millions in earnings to lean back on, which has been funneled into investment portfolios, charity endeavors, production companies and athleisure lines. They have their pick of coaching and broadcasting jobs. They can try to reinvent themselves as owners or politicians or musicians. They can spend more time with their families. They can go drink on a golf course.

But so often, their restlessness draws them back to the only schedule they’ve ever known — a simple one, bifurcated by a season and an offseason. In his recent docuseries, The Captain, Derek Jeter said that he knows very few retired athletes who feel fulfilled playing golf three days a week. In your playing days, restlessness is a superpower; it gets you out of bed at five in the morning, it helps you shake off a bad play or loss, it helps you get faster at 35 than you were at 25. In retirement, restlessness is a tick. No career the world can offer you could possibly beat the one you built yourself.

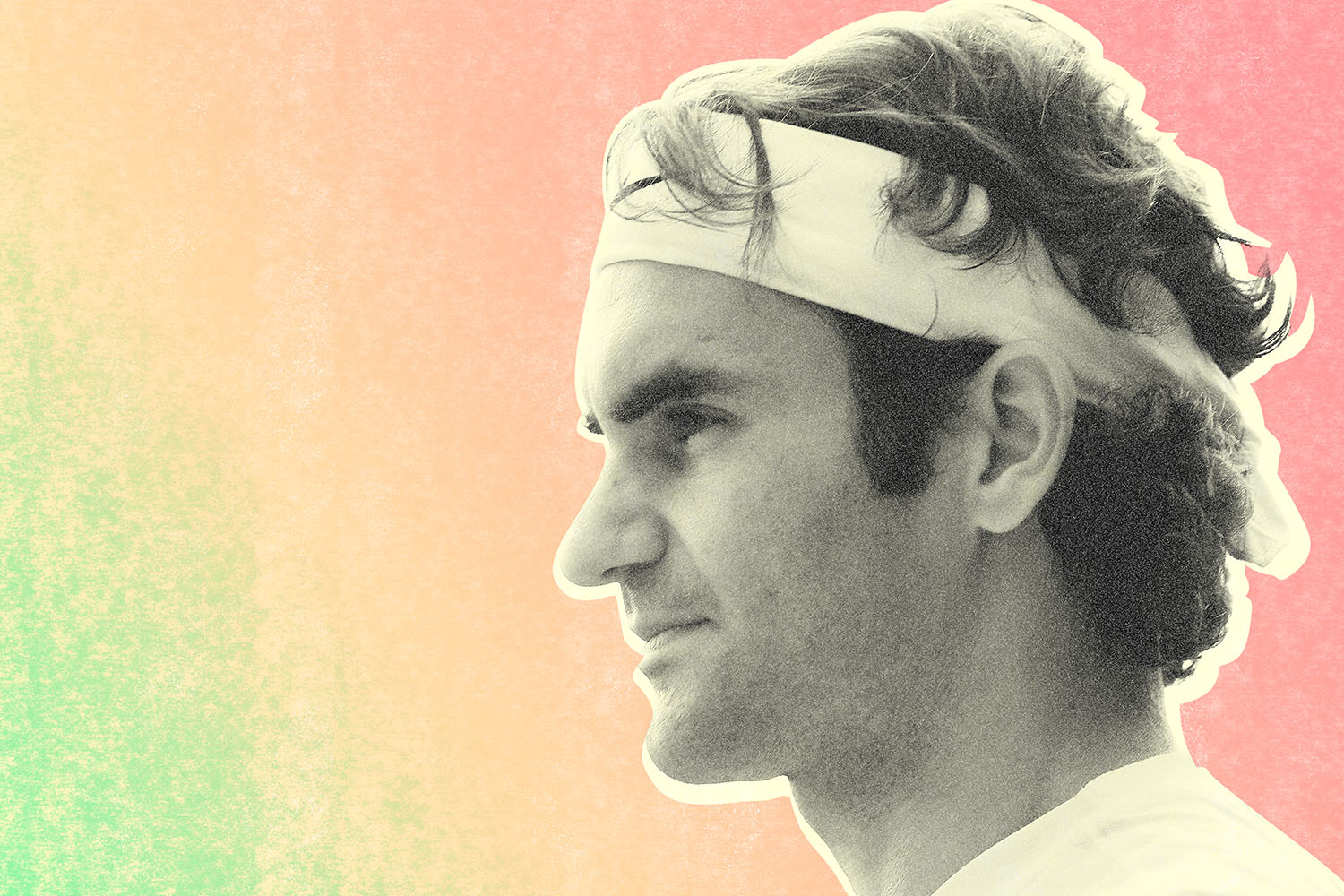

How rare, then, that it’s difficult to detect any sense of restlessness in Roger Federer’s retirement news this morning.

The 41-year-old Swiss tennis champion — if not the greatest to ever play the game, certainly the most elegant — will play the Laver Cup in London two weekends from today. And that will be it. Nearly a quarter century of greatness will come to a close, and with over 1,500 matches and 20 Grand Slams to his name, Federer will begin the daunting task of…doing something else.

He’s the perfect man for the job. Federer will always be compared to his legendary peers, Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic, but you could just as easily put him next to Tiger, Brady or Ronaldo; he’s a legend from an age of legends. The stop-at-nothing, “To give anything less than your best is to sacrifice the gift,” mentality has led all of them to long and stupefying careers. But while these other men seem obsessed with finding the fountain of youth, Federer appears to have quietly discovered an “off switch,” which, in the end, has left him happier, healthier and brimming with hope for the future.

In August 2021, staring down a lengthy road to recovery after his third arthroscopic knee surgery in 12 months, Federer checked in with his fans on social media. He was chummy, measured, honest. “I want to give myself a glimmer of hope to return to the tour, in some shape or form,” he said at the time. “I am realistic, don’t get me wrong. I know how difficult it is at this age right now to do another surgery and try it…I’ll go through the rehab process with a goal, while I’m still active, which I think is going to help me during this long period of time.”

That fall, he said some other things. Like: “My life is not going to fall apart if I don’t play another Grand Slam final.” And: “This is also for my life. I want to make sure I can do everything I want to do later on.”

Athletes don’t die when they retire. We act like they do, because to us, it kind of feels like it. The clubs and leagues and networks encourage this, with bronze plaques and bizarre gifts and drawn-out thank yous. But what is the athlete supposed to make of the morbid pageantry, with over half of their life left to live? How does that play on one’s psyche? It almost makes sense to go back, right? Where else could you ever find such religious affirmation in your private life?

Federer is acutely aware that he is alive. And he has laid the groundwork for his next step for years. Elite athletes don’t need to put money away for retirement like the rest of us — but they do need a plan for budgeting their time. Federer is well-prepped there; it’s no coincidence that his last match will be at the Laver Cup in London, a unique tournament that pits “Team Europe” against “Team World,” and which he co-created and founded in 2017. Speaking to InsideHook in 2020, TENNIS Magazine editor Nina Pantic called the Laver Cup “the most entertaining new addition to the game.”

In the final line of today’s Instagram post, Federer wrote, “Finally, to the game of tennis: I love you and will never leave you.” We can’t say for sure what form his involvement will take. More tournaments? Special advisor to the ATP? A program to mentor and develop young talent? Perhaps all of the above. One thing is clear: this is it. Federer hasn’t quieted his restlessness, he’s just channeled it elsewhere.

We’re left to cherish the uncommon career he gave us, but even more, to appreciate this uncommon goodbye: “The last 24 years of my life have been an incredible adventure. While it sometimes feels like it went by in 24 hours, it also has been so deep and magical that it seems as if I’ve already lived a full lifetime…I have laughed and cried, felt joy and pain, and most of all I have felt incredibly alive.”

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.