Ronald Acuña Jr. had what by many accounts was an incredible season last year. He was the unanimous choice as National League MVP, in large part because of one seemingly outstanding portion of his overall stat line. As MLB.com wrote when he was announced as the award’s winner, Acuña “did the previously unthinkable by becoming the first player to hit 40-plus homers and tally 70-plus steals in a season.”

You know what actually made it thinkable, though? Bigger bases and limits on pitcher pickoff attempts.

It’s MLB Opening Day. So Why Doesn’t It Feel Like It?

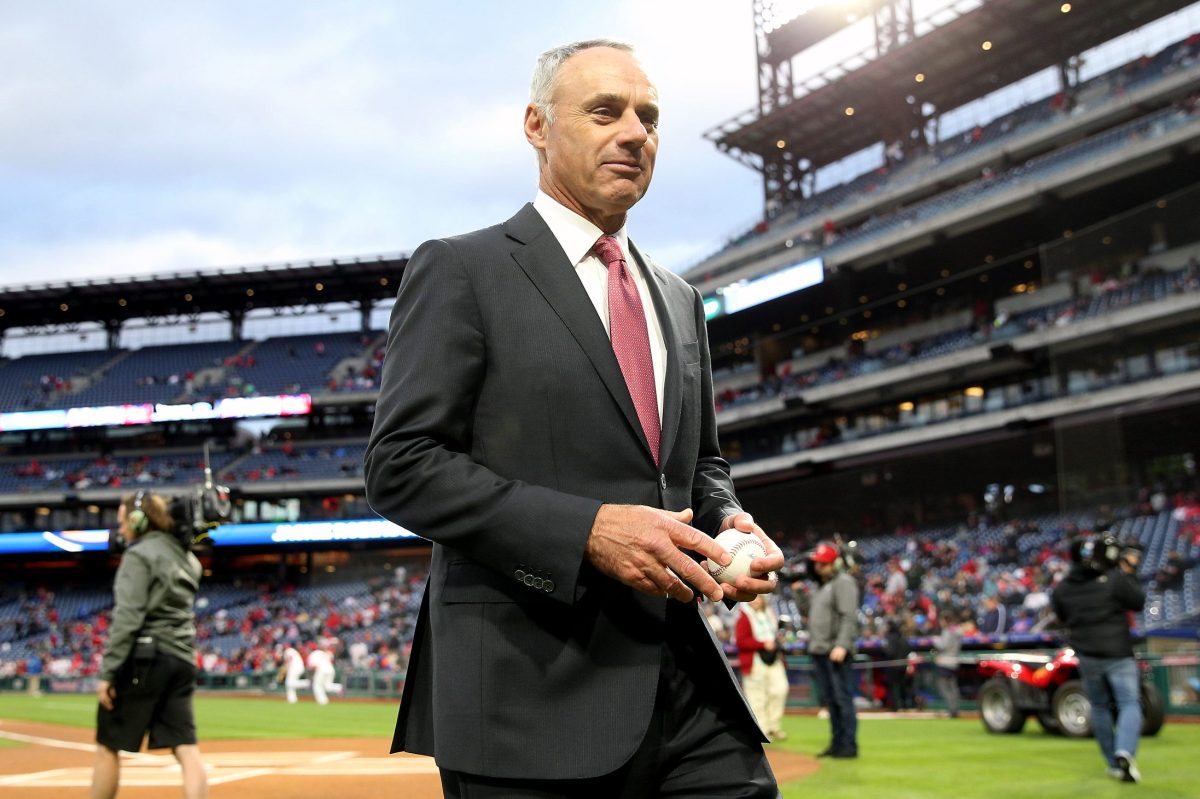

Our writer loves baseball, but he wonders if the new rules are turning America’s pastime into a bummerThis is where my mind goes when I hear the name “Rob Manfred” and why I’m so happy he’s stepping down as MLB Commissioner in five (probably long) years. In spite of my Mets fandom, I don’t mean anything personal against Acuña, who plays for New York’s rival, the Braves of Atlanta. But I’m not really impressed by that particular feat of his from 2023, because Manfred manufactured it with dramatic rules changes that altered the way the game is played. And baseball’s worse off for it.

For decades, one of the most appealing things about being a baseball fan was comparing stats between players across generations. Maybe there was always an illusion that we could compare what Honus Wagner did to the achievements of, say, Tony Gwynn; after all, Wagner never faced a pitcher the color of Gwynn’s skin, nor did he travel on planes to places like San Diego, where Gwynn played his home games. And player stats across generations have been rendered meaningless for 30 years, now, thanks to Manfred’s predecessor, Bud Selig, turning a blind eye to the proliferation of steroids in MLB.

But Manfred and his capitalist agenda has continued to reshape baseball into something that increasingly less resembles the game I fell in love with as a kid in the 1980s. I get why he’s done so, probably more than most because I reported on why professional sports, including baseball, need to attract and retain young fans. Data says the youths — and a growing number of Americans overall — don’t like baseball because it’s “slow” and “boring.” Manfred felt he had to legislate more “action” into MLB, while also shortening game times. His approach may have “worked,” but not without alienating some of baseball’s most die-hard fans who’ve loved the sport since before they could capably form memories.

And Manfred probably never needed to do it in the first place. Baseball has seen tactic trends flow throughout its history, and there was some evidence that action was naturally going to return to the game in the form of increased traffic on the base paths. It was just going to take some time. Though hitters were being taught to increase launch angles to hit more home runs, which meant that runs could be scored more efficiently by a team in light of better pitching capabilities, doing so just wasn’t going to work for many players. A number of them in recent seasons decided to shorten their swings to simply make better contact and let the ball fall in for base hits (see: Jeff McNeil and Travis d’Arnaud, among others). There were also players learning to beat the shift, which was also banned by Manfred. More runners on the bases would’ve meant more pressure on pitchers and defenses, which would have also been boosted by greater aggression on the part of runners through stolen bases.

Furthermore, Manfred’s pitch clock may have led to greater pitching injuries last year, and his new playoff format arguably gives teams with worse records across MLB’s very long regular season an advantage. (So many days off for the top teams who’d earned first-round byes was bound to throw off their performance after playing 162 games in 180 days.)

I could go on and on about other hasty changes to MLB that Manfred’s made, which have distorted and deteriorated his own on-field product, including the latest involving team uniforms of obscene quality. But just as his predecessor was no better — with the steroid thing, the infamous work stoppage in 1994 and the institution of video review — it’s probable that his successor won’t be either. Like Manfred and Selig, they will also work for the team owners, who strive primarily for returns on their investment and not necessarily the retention of so much that made the sport appealing in the first place. I bet they’ll love the robot umpires that will totally suck, too.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.