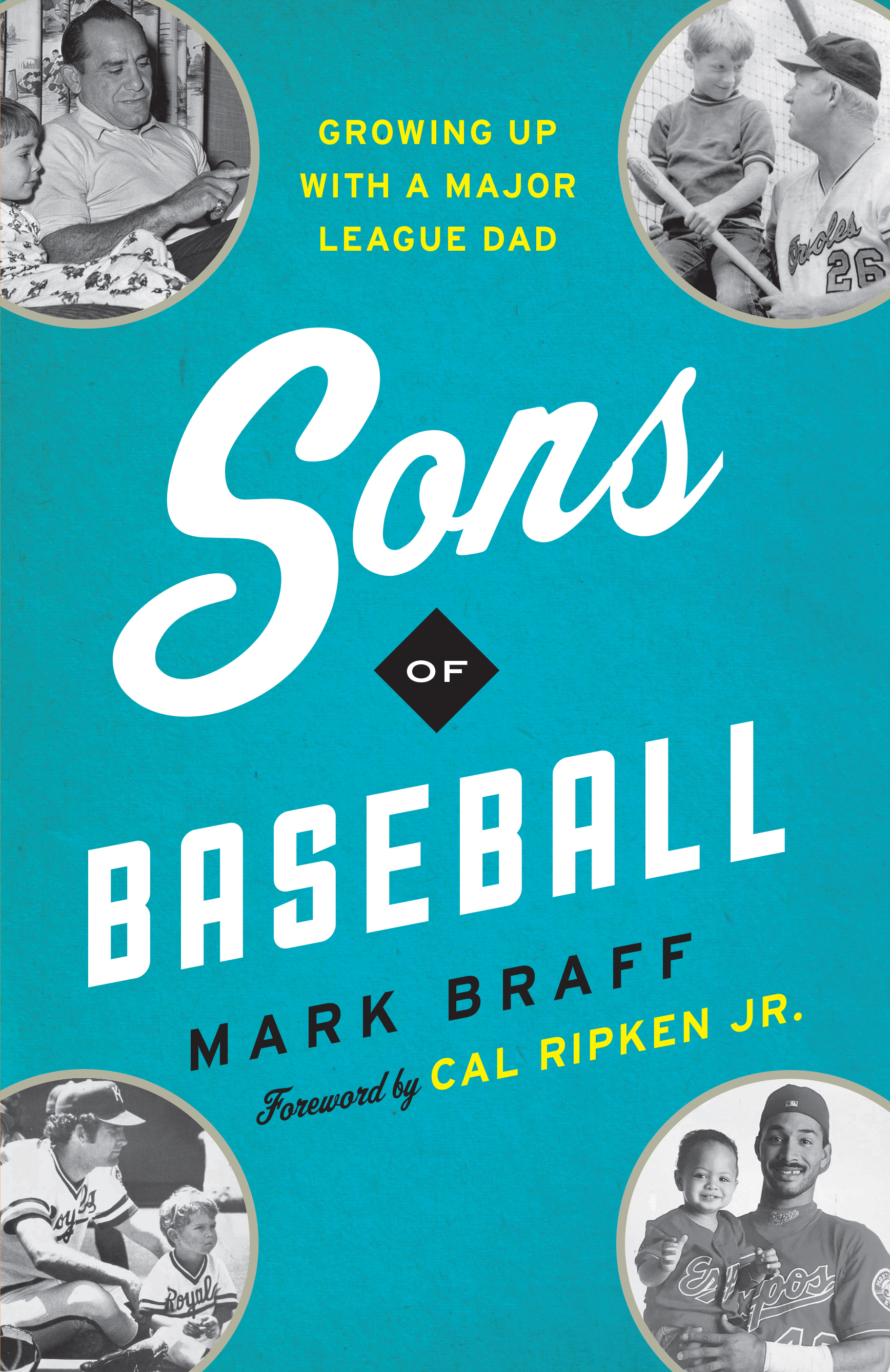

In his new book Sons of Baseball: Growing Up with a Major League Dad, author Mark Braff interviewed 18 sons of star ballplayers including Yogi Berra, Roger Maris and Gil Hodges about what it was like having a father who played Major League Baseball. In this excerpt (“Come on, Rivera, Throw the Cutter”) courtesy of Rowman & Littlefield, Mariano Rivera’s son Jafet shares his experience growing up as the son of “The Sandman.”

Who was the greatest hitter of all time: Babe Ruth? Ty Cobb? Ted Williams? Tony Gwynn?

Who was the greatest starting pitcher of all time: Walter Johnson? Sandy Koufax? Bob Gibson? Greg Maddux?

Who was the greatest closer of all time? Mariano Rivera…period.

When it comes to discussions of the greatest of all time in baseball, or any sport, there is room for considerable debate and, indeed, countless hours have been spent doing just that in taverns and living rooms across the country.

But when it comes to closers, the discussion usually starts and ends with one man: Mariano Rivera.

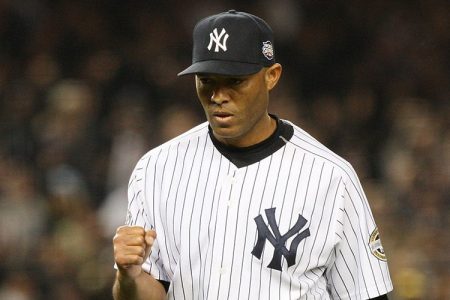

Rivera made his mark as the closer for the New York Yankees from 1997 through 2013, a period in which the team won four World Series and made the postseason “tournament” in all but two seasons. He was named World Series Most Valuable Player in 1999 and American League Championship Series MVP in 2003.

To be fair, in any given regular season during Rivera’s remarkable run with the Yankees there were others around baseball who were just as good, and in some cases even better. But Rivera stood alone in his longevity and postseason greatness. His ability to remain at the top of his craft for such a prolonged period of time and to take his game to an other-worldly level in the playoffs is what set him apart from the rest.

In the postseason, Rivera pitched to an astounding 0.70 earned run average across ninety-six games and 141 innings, with forty-two saves (a record, and an apropos one at that, since 42 was Rivera’s uniform number). Postseason opposing lineups, by definition, are generally among the best and deepest in the game, and of course, the late innings of these games are pressure-cookers. Yet Rivera somehow elevated his performance. His regular-season career ERA was 2.21, the lowest in the live-ball era among qualified pitchers, but that’s still three times higher than his postseason mark.

The Panama native was a thirteen-time all-star and five-time World Series champion (four as the team’s closer and one, in 1996, as the set-up man for closer John Wetteland). Rivera holds the major league record for most career saves, 652, and finished in the top three in the Cy Young Award voting four times. And it was all done with essentially one pitch, his signature cut fastball.

His accomplishments and standing among his peers were recognized when he was voted into the Hall of Fame’s class of 2019 in his first year of eligibility as the first—and still the only—unanimous selection by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America. His induction ceremony was attended by an estimated fifty-five thousand people, including Laurentino Cortizo, the president of Panama, where Rivera can best be described as a living legend.

A devout Christian, “The Sandman” was presented with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2019 in recognition of his charitable work, which includes the Mariano Rivera Foundation.

Jafet Rivera is the second of three sons born to Mariano and Clara Rivera, entering the world in 1997, the year his father started his long run as the closer for the Yankees. Jafet was born in Panama but moved with his family to Westchester County in New York when he was three or four years old. It didn’t take long for him to figure out that his father wasn’t a regular suburban dad.

“Early on, I knew he was very different from all the fathers because he wasn’t able to be there for the little things, like if there was a father-son thing at school, or a play, or a graduation from elementary school and things like that, or like, parents would just come and pick up their kid from school and things like that. I knew that he was different because he couldn’t go to those things. And then all the teachers, they would be like, ‘Oh, how’s your dad? Tell your dad I said good game.’ Or, ‘Your dad did great last night.’ I think it was second grade when I knew, okay, Dad’s an athlete and he has to do this. I just understood that it was just part of my life, you know? I wasn’t going to grow up the way that all the other kids grew up.”

“We couldn’t really go anywhere and have privacy. Everybody always recognized him and asked for a picture or an autograph. Sometimes I [liked it] because it was like, oh, cool, they’re asking my dad for a picture, an autograph. But most of the time, it was like, man, I just don’t want to share [him] right now. I don’t want anybody to come, I just want him for myself. I just want this time to get to really talk to him about how he’s doing and for me to express how I’m doing. And so, we really didn’t get that part, you know? My close friends knew that my life was different. One time, a friend went out [with our family] for dinner. He got to experience my life, and he was like, ‘You do this? This is crazy!’”

“Of course, there were so many great things that I’ve been privileged and blessed to be a part of. For starters, you have the greatest of all time as your dad. That’s just to start. And then, the house, the places you get to eat at, the places you get to go to, the people you get to meet. It was just surreal. But then, it’s also difficult sometimes, where it was like, okay, I just want to hang out with Dad and I just want to chill, you know? But I couldn’t ’cause he had to go. He would leave in the morning, maybe like nine, and then would come home at around 11 [at night].”

“So, when we were growing up, we really didn’t get to see him that much. It would be like periods, days, where we would spend like very few times with him unless you went to the stadium. That was when we got to see him for a little bit. And, for me, I’ll always cherish those moments. I think the most memories that I have growing up are the old stadium [the Yankees moved out of their original stadium after the 2008 season], predominantly because of the relationships that I’ve formed with other players’ kids. I spent more than half my life at Yankee Stadium. I was super close with Bernie [Williams’s] kids, Andy Pettitte’s kids. We would go to this playroom [at the ballpark] and my brother and I would stay there until like the seventh inning. And then my mom would come in and she would grab us and would take us up in the stands to see him [pitch]. The thing is, we wouldn’t want to go because we were young; we just wanted to play. We played wall ball in there. But when they won, we got to go see him in the clubhouse. So, when the Yankees won, the song would come on [Frank Sinatra’s “New York, New York”] and we would run down [to the clubhouse].”

“There was this entrance that we would go down. You could smell like the paint, like the stairs had a certain type of smell to it. And the clubhouse was just awesome because when you got in, you see all the players lined up and they’re high-fiving. So, me and my brother, we would sneak in and just high-five the players. So, that was definitely fun. I mean, you saw guys like [Derek] Jeter, Hideki [Matsui], A-Rod [Alex Rodriguez], [Jason] Giambi, Jorge [Posada], Alfonso Soriano, all these great guys. Paul O’Neill, Tino [Martinez], like everybody’s there.”

Mariano Rivera’s ‘Enter Sandman’ and History of the Baseball Walk-Up Song

How the music played when players take the field or step to bat has changed the game.The players’ kids weren’t allowed in the clubhouse after a loss, but “they won a lot, so there weren’t many days that we didn’t get to go in.”

Sometimes, Dad’s baseball pals would come by the Rivera house in Westchester.

“He was very good friends with Ramiro Mendoza [a pitcher]. He’d come over the house. Bernie Williams and Jorge [Posada] would come over, too. It was routine. To me, it was just like my parents’ friends, you know? When I’d go on road trips, that’s when it would hit me. It was like, I’m really with these guys! When we got old enough to where we could actually go on the plane with the team, he took us to like four or five away trips. My favorite was when we went to the West Coast when they played Seattle, San Francisco, and L.A. I loved those. You’re on the plane with the whole team. The manager was in front with the coaches. My dad would always be in the middle and then the back was always nuts.”

Jafet played some baseball himself, an experience that he says was “crazy.”

“In Little League, I had no care in the world. It’s Little League, everybody’s just hitting the ball, running around the bases. I was always an athlete. I was always fast, and I knew how to play ball. Travel ball, I guess when I got to middle school, you started to have tryouts and things like that, and that’s when it started to become, instead of fun, more of an expectation. That’s when it started. People would come to the games, and they would already know who I was. I was a pitcher, so there’s already an expectation of being the next big thing. And it’s like, I just wanted to have fun, you know? I just wanted to play the game. And so, as the years progressed, I just started noticing that I put more and more pressure on myself because of the pressure that people put on me. Like, there were literally games when parents would be chanting, ‘Come on Rivera, throw the cutter.’ And it’s like, are you serious? I’m thirteen. Thirteen! What do you want from me? I just threw fastballs. That’s all my dad ever taught me, just throw a fastball.”

“Dad wouldn’t give me a tremendous amount of advice. I don’t think he really wanted to push or force anything on me. I think in some sort of way he knew that we already had a lot of pressure on our backs. It was so stressful when he would come to a game. So stressful. The last game that I ever played baseball was in my junior year of high school. And I did terrible. And I just never played again. I mean, I knew I could pitch, but after that game, I was just so tired [of baseball]. Plus, I wanted to do soccer more. But it was just a brutal game, and it was just embarrassing. And this is high school, so kids don’t care what they say. So, they’re chirping and it was crazy. It was definitely crazy. I mean, [Dad’s] not just a regular ballplayer. He was a mega-celebrity. I didn’t want to have to pretend to live up to something that I wasn’t. I wasn’t going to do that.”

Today, Jafet is working on completing his college degree and helps run events for the Mariano Rivera Foundation. Most of his extended family still lives in Panama. Pre-COVID, Jafet and his immediate family would try to visit Panama at least once a year, which he describes as an experience unlike any other.

Despite the unique challenges, Jafet says he wouldn’t change anything about his childhood.

“I wouldn’t change anything because the lifestyle that we had and the way that we grew up made me into the person that I am today. I think I’ve learned a lot of lessons from just watching [Dad] and just from being around him, even at the ballpark, like things about the game that I could put into something else in everyday life. There was a lot of good, and there was bad, but you learn from those. I learned to appreciate those moments because they were moments of growth.”

Excerpted from the book Sons of Baseball: Growing Up with a Major League Dad, by Mark Braff. Used by permission of the publisher Rowman & Littlefield. All rights reserved.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.