A lifelong climber and former outdoor guide, Will Cockrell covered Mount Everest throughout his career during stints at publications including Men’s Journal and Men’s Fitness and freelance gigs at Outside and GQ. After spending more than two decades as an adventure journalist, Cockrell decided it was time to take all of the knowledge he’d accumulated over the years and write a book.

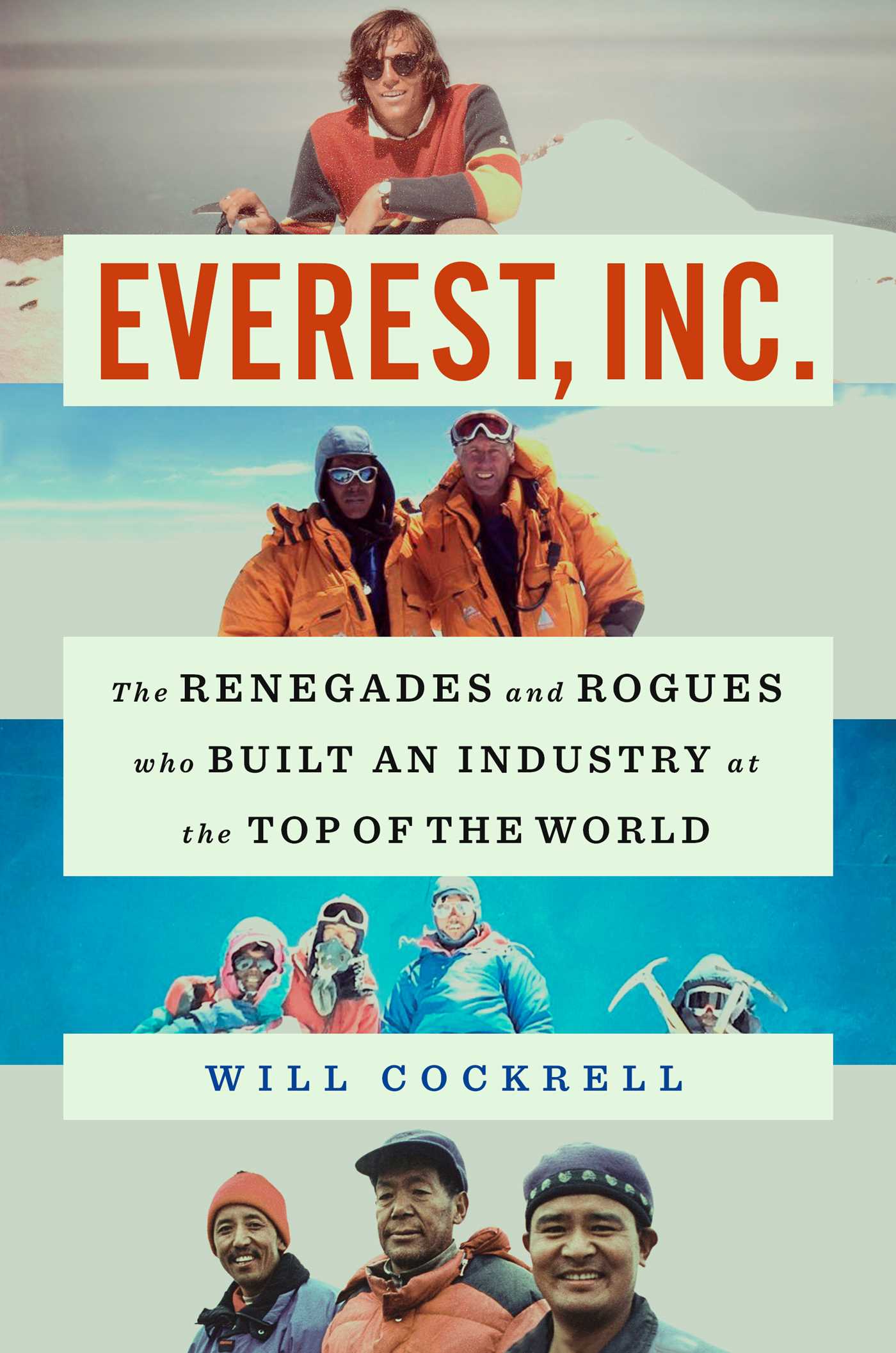

The result is Everest, Inc.: The Renegades and Rogues Who Built an Industry at the Top of the World, a work that incorporates plenty of Cockrell’s firsthand knowledge as well as interviews with Western and Sherpa guides in the Himalayas and climbing icons like filmmaker Jimmy Chin and Patagonia founder Yvonne Chouinard.

As Cockrell, whose work has been awarded by the American Society of Magazine Editors and the Professional Publishers Association UK, explains, Everest, Inc. is somewhat of a counter-narrative to the majority of the mainstream media coverage of Earth’s highest mountain over the last 40 years.

“There’s always a big sensationalist spin about the mess on Everest. Having covered so many of those events and met so many people in the Everest world over the years, I always felt like those stories weren’t quite right,” Cockrell tells InsideHook. “Sometimes they were misleading or just wrong. I knew the doom and gloom and the greed and colonialism that was presented could not be that bad knowing who I did and what I knew about the industry.”

In advance of Cockrell’s book hitting shelves, we spoke with him about all things Everest.

InsideHook: What’s the biggest misconception people have about Everest and the industry surrounding it?

Will Cockrell: That’s a good question. I think a lot of it has to do with how soulless it is. The romanticism of climbing dictates you climb mountains a certain way with a certain amount of dues paid and self-sufficiency. As a climber, I totally believe in all those things. From a climber’s perspective, the idea of paying a lot of money to climb Everest rips the soul out of what climbing is all about. A lot of people readily admit they’re not looking to become climbers or mountaineers. They just want to climb Mount Everest. The overarching idea is anyone who goes to climb it thinks they’re a climber who’s following the rules of climbing. That’s not really the case.

Virtual Insanity — Filming Alex Honnold for VR Requires Climbing With Him

Director Jonathan Griffith literally hung out with the world’s foremost free soloist while filming “Alex Honnold: The Soloist VR”IH: How profitable is it for the guides and companies that are leading expeditions up Everest nowadays?

WC: These days, a top-end Western guiding company might charge somewhere around $100,000 per person. The Nepalese companies are charging about half that. People think that all that money changing hands brings up a huge conflict of interest. If you have 10 clients who paid a ton of money to climb the mountain, you’re under pressure to get people to the top. Imagine you have a high-powered lawyer in the group who is a little difficult to get along with and is insisting he gets to the top regardless of what happens. At the surface level, that pressure and the money create a conflict of interest. That’s another misconception. There really isn’t much money to be made in the Everest industry. Most of the Western companies proved to me it’s a loss leader for them because it costs so much to do the expeditions. A lot of them admitted to me they just want to be seen as an Everest company. It’s important to them.

IH: Are the Nepalese guiding companies also just barely breaking even or losing money?

WC: For a developing country like Nepal that’s quite poor, business is booming in a way that is actually changing a lot of people’s lives. It’s a huge international industry within their country that’s benefiting them a lot. I don’t know how sustainable it’s going to be, but I will say it’s making a difference financially. What it’s doing for the Sherpa people and the Nepali people is probably cooler than anything we’ve seen in the 40-year history of guiding.

IH: There was an all-time Everest high of 18 deaths in 2023. With more attempts each year, will deaths increase?

WC: That’s probably the other big misconception among a lot of people. The goal is zero deaths, and the Everest guiding industry is designing the industry around the least-experienced people and worst-case scenarios. How do we manage climbs in a way that nobody dies even if everything goes wrong? The truth is the industry has done a remarkable job in achieving that. For the wide spectrum of people who climb Everest these days with guides, the death rate is shockingly low, for what it used to be. A mountain that used to be considered unclimbable and later suicidal now has 12-year-olds going to the summit with the help of guides. It will continue to get safer. You can imagine how a climber feels about that. We’re watching them dismantle every element of risk from climbing a mountain. Hardcore climbers feel Everest is turning it into a hike. If every single bit of risk is eliminated, they’re asking, “How is that fulfilling?”

IH: Did the process of reporting and writing the book increase your interest in climbing Everest yourself?

WC: I had some mixed emotions there, but I’ll admit my feelings about that are largely dictated by the fact that I have two kids. I have no interest in doing that type of climbing in my life for that reason. I have gone to base camp, and it’s one of the most incredible places in the world. I’m dying to take my family back to do that trek as soon as I can. It’s incredible and pretty much anyone can do it. Being at 17,500 feet, I felt crushed for the few days I was there, but it’s a really special place. You meet so many interesting people and there’s co-mingling between Sherpas and Nepalis and Westerners. There’s sort of this equity that is nice to see. I did look up at the mountain and picture myself on it a couple of times, but I wasn’t thinking seriously about it.

IH: At base camp, did you see anyone who was climbing Everest because they were an influencer?

WC: That’s very real. I was right next door to a Nepali company that’s known for taking influencers to the top, so I saw a lot of them. In a way, they are climbing Everest to get a selfie at the top. Sometimes I’d think there was no way they could have an understanding of what it takes to climb it. I had to remind myself that’d put me in the camp of deciding who deserves and doesn’t deserve to be on the mountain. That’s a more judgmental person than I try to be. I can understand a certain type of person saying Everest doesn’t interest them anymore because of all the selfies on the summit, but is it fair for me to judge a person’s reason for coming to the mountain? I don’t know. It’s no one’s mountain.

IH: Is there anything specific you’d like people to take away from reading the book?

WC: Number one, that almost every story you read about Everest is locked into one narrative. That narrative is not quite right. Every story and photo caption is sort of anchored in the idea Everest is a mess. How do we fix Everest? I think that’s a lazy premise. The second thing would be being able to see the desire to climb Mount Everest as a cultural phenomenon rather than a mountaineering challenge. That might completely reshape your judgment of what goes on on the mountain. Trying to get everything right on Everest is insanely difficult, but I’m heartened by the idea that a lot of people are trying.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.