In a 1959 article for Sports Illustrated titled “You Could Blame It on the Moms,” Martin Kane — the magazine’s boxing and fishing writer at the time — lamented the steady decline of collegiate boxing. His headline was in reference to a sound bite from a disgruntled college coach: “You could blame the moms. They’ve seen boxing on TV, and nothing can persuade them that the college sport is different, that their boy stands little risk of being hurt.”

Kane pointed out that despite protective headgear, 12-ounce gloves with foam padding, and the presence of judges trained to reward defensive work and referees incentivized to stop a bout the second a competitor looked outclassed, the sport was dying at the scholastic level. It faced certain “annihilation,” due to “false identifications with prizefighting,” and the insidious nature of supposed hidden brain injury, or “punch-drunkenness syndrome,” which, according to Kane “[there is] no good reason to believe the condition…has ever has occurred as a result of college boxing.”

A little over a year after SI published that article, a middleweight boxer at the University of Wisconsin-Madison named Charlie Mohr died of a brain hemorrhage — eight days after competing in the NCAA Tournament. His school abolished collegiate boxing less than a month later. The entire NCAA followed suit, officially terminating the sport across the country.

That’s right. Four years before a 22-year-old Cassius Clay knocked out Sonny Liston in seven rounds, American higher education banned competitive conference boxing for good. Unsanctioned events continued on, assuming various forms: training clubs, fundraisers and inter-house bouts (most of them) at the discretion of college campuses. And a school that fought as hard as any other to keep this tradition going, believe it or not, was Harvard.

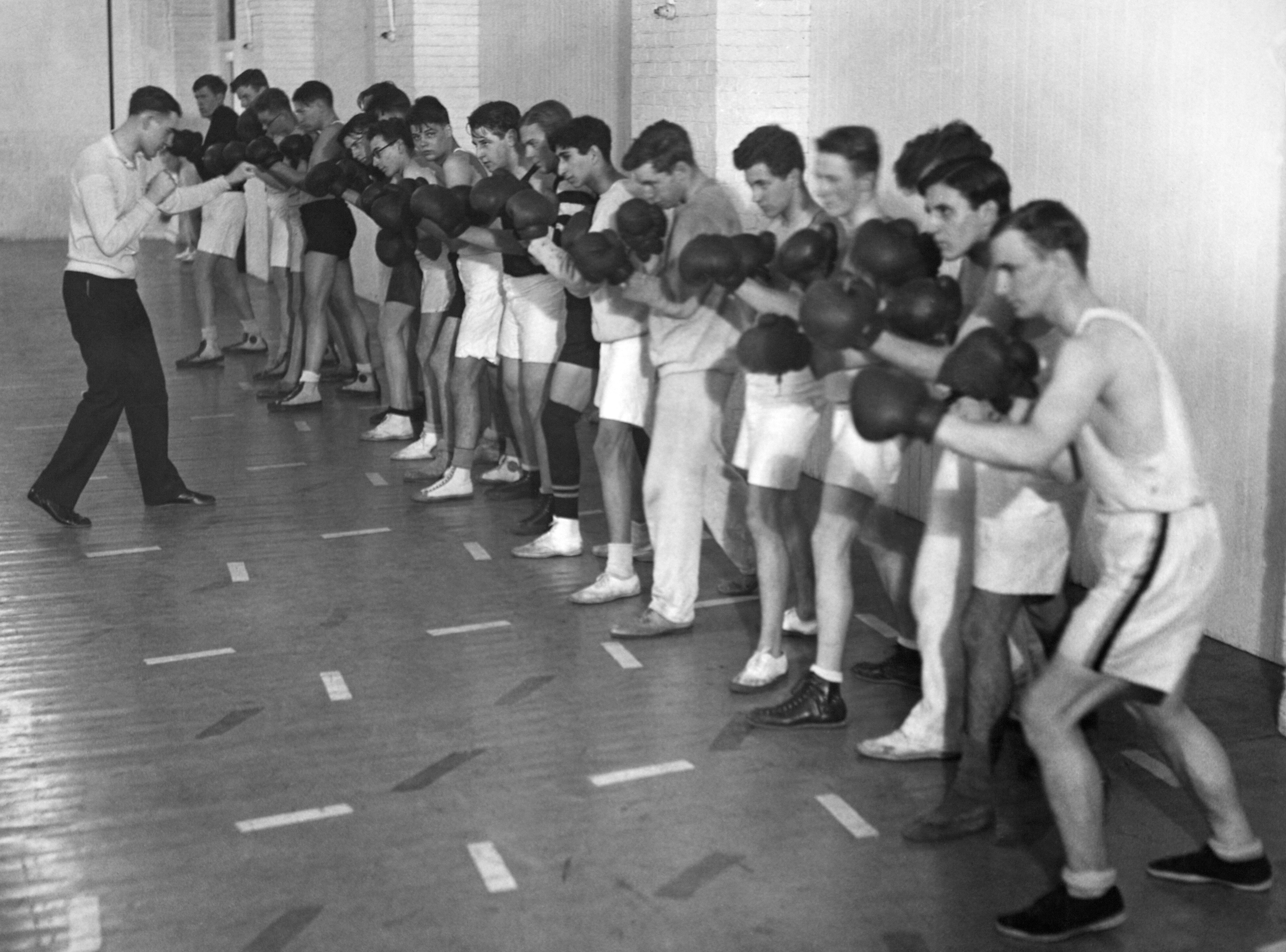

Cambridge, Massachusetts, spent the 20th century producing world leaders, novelists and titans of industry, and most of those graduates were at one point put in a room and instructed how to throw a punch. During World War II, boxing training was a required sport. A physical education requirement in itself wouldn’t have been particularly novel in mid-century America — in 1920, 97% of undergrads at four-year universities were required to meet physical education goals; it was common for that mandate to include some combination calisthenics, swimming and “combat” sports — but boxing holds a special place in Harvard lore.

The Untold Story Behind Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney’s Welsh Football Club

48 hours of songs, pints and unexpected friendships. This is one adventure you won’t see on the FX series “Welcome to Wrexham.”The institution’s most famous 19th-century graduate, President Teddy Roosevelt, was a big reason why. Once described as a “locomotive in human pants,” the American Lion was known for his mix of gallantry and energy, an unusual cocktail that took stodgy, 1870s Harvard by surprise but clearly managed to win it over in due time. The Harvard Crimson has published accounts of Roosevelt’s boxing talent over the years, acknowledging that “the anecdotes are only too characteristic, but of doubtful veracity.” They’re fun, though. Here are two:

“Frederic Almy, [Roosevelt’s] class secretary, recalls that during a torchlight procession in the Hayes-Tilden presidential campaign a bystander on the sidewalk said something derogatory. The impulsive Teddy thereupon, recording to Almy, ‘reached out and laid the mucker flat…Then, at the Harvard gym in March, 1879, Roosevelt won his first match, and also won the crowd with one of those chivalrous acts which sporting fans love. When the referee called ‘Time,’ Roosevelt immediately dropped his hands, but the other man dealt him a savage blow in the face. The spectators shouted ‘Foul, foul!’ and hissed, but Roosevelt is supposed to have cried out ‘Hush! He didn’t hear.’”

Roosevelt is a compelling mascot for Harvard’s love affair with boxing, as an unexpected collision of intellectualism and individualism. Still his role is boxing history is tricky (just as it is in American history). T.R. called for the end of professional prize fighting after Jack Johnson became the nation’s first black heavyweight champion, yet changed his tune the second Jess Willard (nicknamed the “Great White Hope”) knocked out Johnson in 1915.

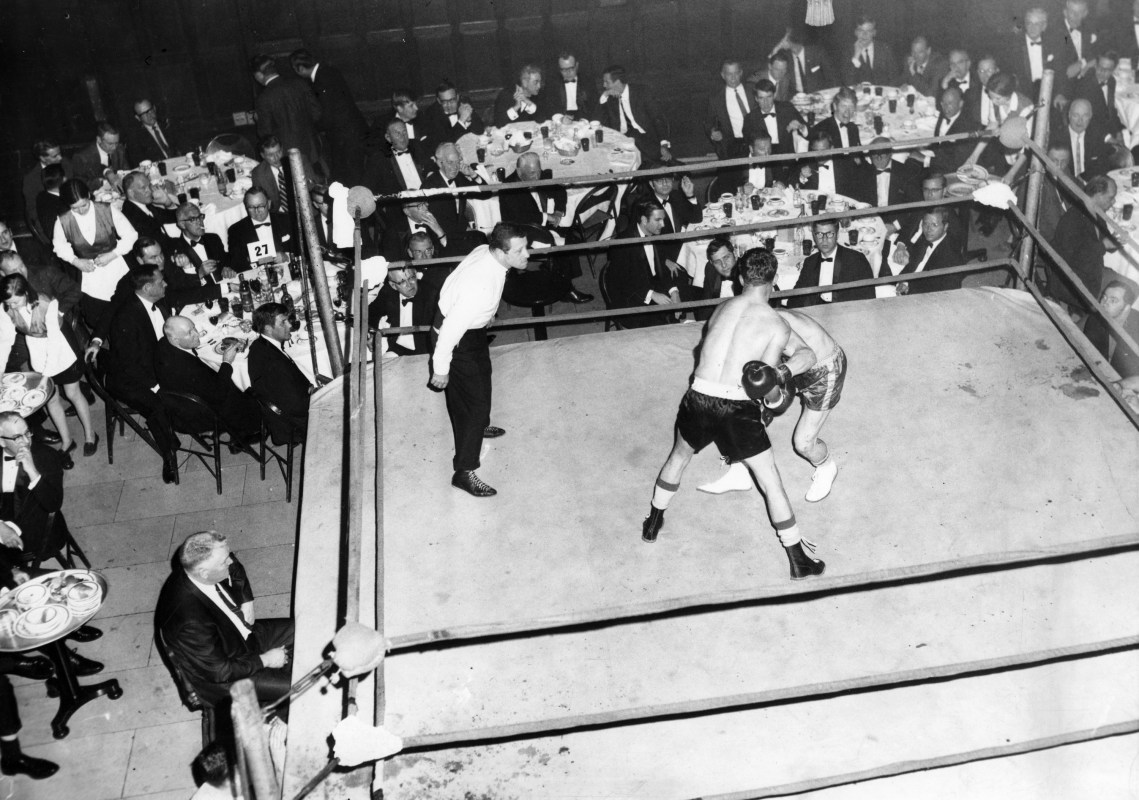

But Harvard’s boxing history is rich beyond the 26th president. Alumni like John F. Kennedy and Norman Mailer also trained with the varsity team in the 1930s, and from the 1960s onward, after the NCAA disbanded intercollegiate boxing, Harvard formed an on-campus team…which, in the late 1970s was downgraded to “club” status. Some of the exhibition tournaments (which would sometimes attract students in suits and gowns, before dances) had become a little too…unruly.

For 60 years, the club was run by Tommy Rawson — who once coached Rocky Marciano and was a legendary lightweight champion in his own right — until Doug Yoffe took the reins in 2001. There are three skill days a week and three conditioning days. It’s fascinating, listening to one former captain of the club talk about why he stayed with the club throughout his four years on campus: “I got into it because I wanted to learn self-defense, but I stayed because it pushes you in a way that classes never can. Physically, obviously, it’s very strenuous. But mentally, you can’t get that feeling anywhere else…of going into a ring, accepting the challenge and coming out whole on the other side.”

We now know that Sports Illustrated was wrong in the 1950s. So too were all the coaches and neurologists who framed punch-drunkenness as an invention in opposition to the “rugged fitness on which our country was founded.” (To quote Kane one last time.) Punch-drunkenness, of course, was CTE all the while; recent deep-dives by boxing experts have confirmed that extensive brain injury was unavoidable in 20th-century boxing, no matter how good you were at it. As an article from The Guardian concluded last year: “Damage is a salutary reminder that almost all great fighters — from Joe Louis and Sugar Ray Robinson to Muhammad Ali and Aaron Pryor — had their senses obliterated by boxing.”

Still, just ask anyone who’s trained in it, at an old-school gym, via shadowboxing, or even with a fledgling app like FightCamp: boxing carries untouchable value as a learned discipline, as a tradition in self-defense, and as a way to test one’s mental mettle. This spirit can coexist with its uncertain history. Harvard has always been associated with privilege. It’s a fair assessment. And that privilege, evidently, also extended to knowing how to throw a halfway decent punch. But kudos to the university for keeping a good thing going. Meanwhile, trainees nowadays have more access to proper boxing training than former presidents could’ve possibly imagined 100 or 150 years ago…and fortunately, without having to take a punch in the face in Harvard Yard.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.