The Fight Of The Century took place in the winter of 1971 at Madison Square Garden in New York City, as Muhammad Ali bid to regain his status as the undisputed heavyweight champion of the world (he was stripped of his titles by boxing authorities for refusing to submit to the draft for the Vietnam War). In the bout, Ali found himself stepping into the ring with WBA, WBC and The Ring heavyweight champion Joe Frazier, who supported U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

Possibly the biggest sporting event in history up to that point in time, the bout was the first time that two undefeated boxers who held or had held the world heavyweight title fought each other for that very title. In this excerpt from The Big Time: How the 1970s Transformed Sports in America, author Michael MacCambridge takes readers inside the fight — and the fallout.

On the eve of the fight, visited by writers to his hotel suite at the New Yorker, Muhammad Ali doubled down on his framing of Frazier as an Uncle Tom and the white man’s choice. “Frazier’s no real champion,” Ali charged. “Nobody wants to talk to him. Oh, maybe Nixon. Nixon will call him if he wins. I don’t think he’ll call me.”

On the night of March 8, 1971, people flocked by the tens of thousands to halls and arenas, auditoriums and stadiums, to watch the closed-circuit broadcast. In Memphis, a sold-out crowd at Ellis Auditorium was packed and included the Ali supporter Elvis Presley, decked out in a $10,000 gold belt for the occasion.

And at Madison Square Garden on the night was…well, everybody. “Stars of stage and screen” doesn’t really begin to do it justice. Frank Sinatra was at ringside, shooting photographs for Life magazine. Burt Lancaster was doing color commentary for the closed-circuit broadcast. Miles Davis sat close to the ring. The French actor Jean-Paul Belmondo accompanied the Italian actress Antonella Lualdi. Isaac Hayes was there, as was Duke Ellington. Joe Namath attended. Sammy Davis Jr. was there, as were Jack Nicholson, Robert Redford and Barbra Streisand. So was Diana Ross, sporting black hot pants. The Bruins’ Bobby Orr, longtime Ali fan, was close to ringside. So were Bob Dylan and Diane Keaton. The Knicks had the night off, so Walt “Clyde” Frazier was in attendance, as was the fanatical Knick follower Woody Allen. Dustin Hoffman and Hugh Hefner were there, the latter with Barbi Benton, who got more attention due to her see-through blouse. Perhaps never before had such a wide swath of American culture — high, low, Black, white, movies, music, sports — ever assembled for a single event.

If the fight was unprecedented, then so was the fashion. And it wasn’t only the crowd that dressed up. For decades boxing matches paired fighters in two of three different hues of trunks: white, black or blue. But in this instance, on this stage, in this decade, nothing so mundane would have sufficed. So Ali arrived, for the first time in his career, in red trunks with white trim, sporting red tassels on his white boxing boots. Frazier’s designer had accommodated Smokin’ Joe’s request for “flecks,” and he sported trunks in a jazzy print of green and gold.

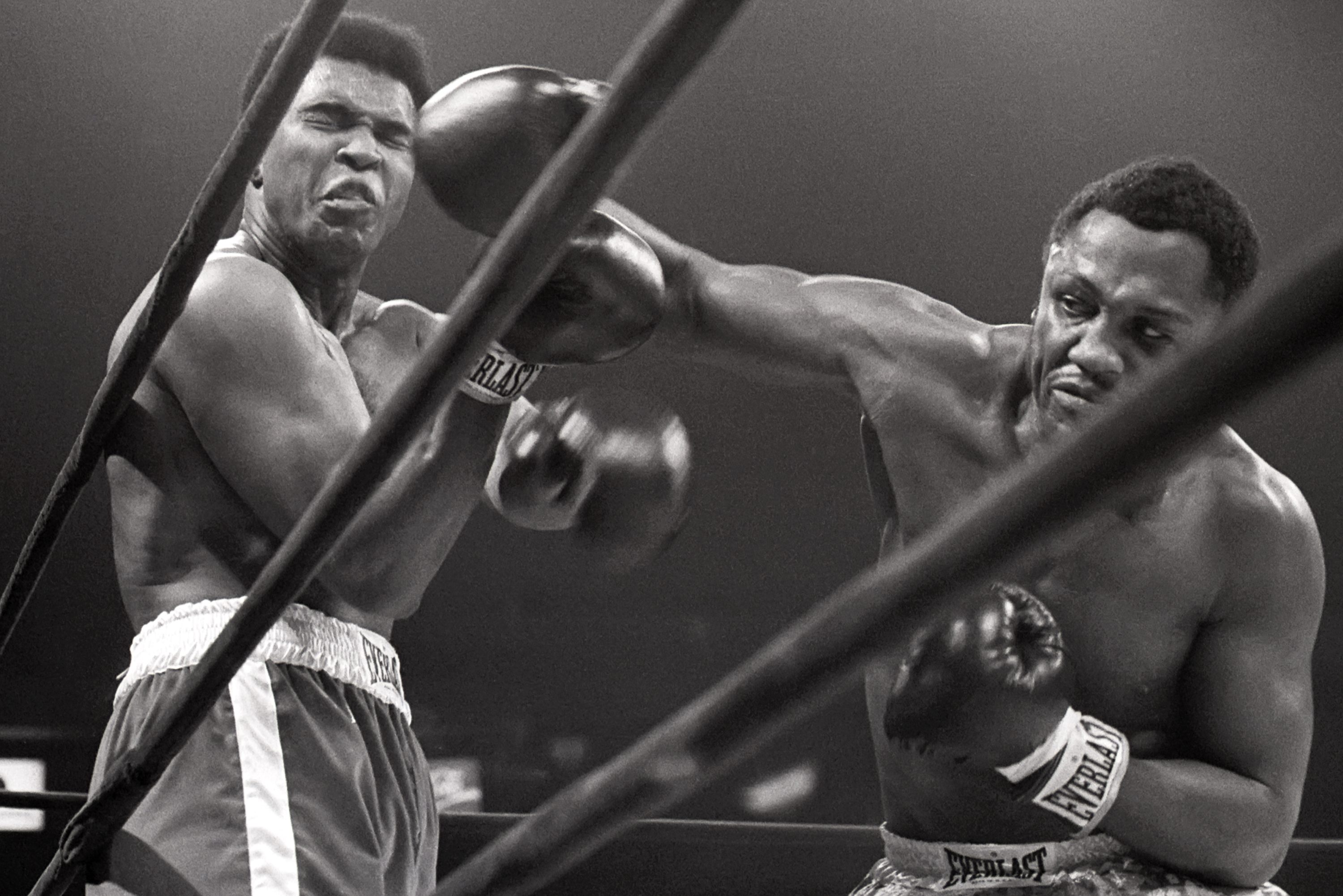

The fight itself somehow lived up to the impossible hype, a perfect blend of styles. Ali’s flowing movement, and his lightning jab from his superior height and reach, meant he was always within striking distance. Frazier, coiled but relentless, bobbed and weaved. Even though he was shorter and slower than Ali, his deceptive, crablike movements made him a surprisingly elusive target. Cutting off the ring from Ali, he burrowed into the previous champ’s midsection, and from close quarters, fired off his dreaded left hook. The battle ebbed back and forth. Ali could still move, but Frazier was implacable. Absorbing punishment in the face from Ali’s jabs, he kept moving in, punishing Ali with body blows and finally connecting with a fierce hook that knocked Ali down in the fifteenth round. It was a startling moment, as shocking to the crowd as it was to Ali himself.

The fight had been close, but Frazier’s stamina and the late knockdown made the decision inevitable. In the commotion after the bell to end the fight, as the fighters moved unsteadily to their respective corners, having survived the draining spectacle, “Bundini” Brown was already in tears, in the forefront of the Ali partisans who’d experienced the unthinkable, watching their prince defiled.

What Muhammad Ali Understood About Taking a Picture

The man called The Greatest was the subject of some of the most enduring images of the 20th centuryThe unanimous decision brought a sense of vengeful glee to the pro-Frazier cohort in the crowd. Just a few feet away from the ring, the German actor Curd Jürgens stood with his wife, the model Simone Bicheron, and, glaring at Ali, said, “He deserved it. He deserved that beating.”

And at the White House that night, the inveterate sports fan Richard Nixon, who’d arranged to have the closed-circuit broadcast screened at his residence, celebrated Frazier’s decision over “that draft dodger asshole.”

In the aftermath of the fight, Frazier sat for the press with a face that was a collage of bumps and bruises. He was at once proud of his accomplishment and respectful of Ali. “Let me go and straighten out my face,” he said in concluding his post-fight press conference. “I ain’t really quite this ugly.” Though Frazier had won, the punishment he endured was enough to keep him hospitalized for an extended stay.

“End of the Ali Legend,” blared one headline — but rumors of Ali’s demise would prove premature. In the hours and days that followed, something curious happened. Ali, the malcontent that white America wanted silenced, became gracious, nearly gallant, in defeat. Like all the great champions before him, he recognized the greatness of his opponent.

Ali’s case had been appealed all the way to the Supreme Court where, on April 19, 1971, oral arguments were heard in the case of Cassius Marsellus Clay, Jr. v. United States. (Ali had not legally changed his name when converting to Islam in the ’60s.) On the morning of June 28, 1971, the decision came down, with the court deciding in a unanimous opinion to overturn the conviction.

In this, too, the hyperkinetic Ali seemed atypically serene and at peace. He cast no aspersions. “They only did what they thought was right,” he said. “That was all. I can’t condemn them.”

Another reporter started to ask a question. “Champ—” he said, but Ali cut him off.

“Don’t call me the champ,” he said quietly. “Joe’s the champ now.”

Somehow, Frazier, for so long hailed the white man’s hope to quiet the loud Black Muslim, became smaller, not larger, in victory. The call from the president never did come that night. And the white America that had seemed to embrace him beforehand suddenly cooled. Embarking on a concert tour of the U.S. with his soul backing band the Knockouts, Frazier played in front of fewer than 100 people at San Francisco’s Winterland.

Things did not improve during the European tour in the spring of 1971 that had been scheduled as a victory lap for Frazier, proof that he was every bit the multi-talented hyphenate that the writer-debater-poet-actor Ali wanted to be. But Frazier, who now had the rightful claim to be the undisputed heavyweight champion of the world, didn’t have that ineffable appeal that Ali would forever possess. There were more than 6,000 empty seats in the 7,000-seat Pellikaan Hall near Amsterdam, and just 250 people buying tickets in Cologne. Frazier sold just 28 tickets for a show in a 3,000-seat hall in Copenhagen. Upon his return to the U.S., Frazier said, “Man, you can’t club people over the head to make them come out.”

Excerpted from The Big Time: How the 1970s Transformed Sports in America by Michael MacCambridge.

Copyright @ 2023 by Michael MacCambridge. Reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.