Trent Preszler gets on our scheduled Zoom call wearing a sweatshirt that reads “canoeist” — a detail that is either cheekily premeditated or entirely routine; I can’t tell which. He’s calling in from Riverhead, a small town on the North Fork of Long Island just a few minutes away from the woodshop where he makes $100,000 canoes by hand.

Yes that’s the correct number of zeroes: his canoes will run you, depending on the day, a pair of bitcoins. But there is nothing new or technological about them. He makes what are known as strip canoes: boats constructed a single strip of wood at a time. Each piece of wood is cut down then shaped into the exact right size and shape, a painstaking process carried out by Preszler and only Preszler over the course of a year.

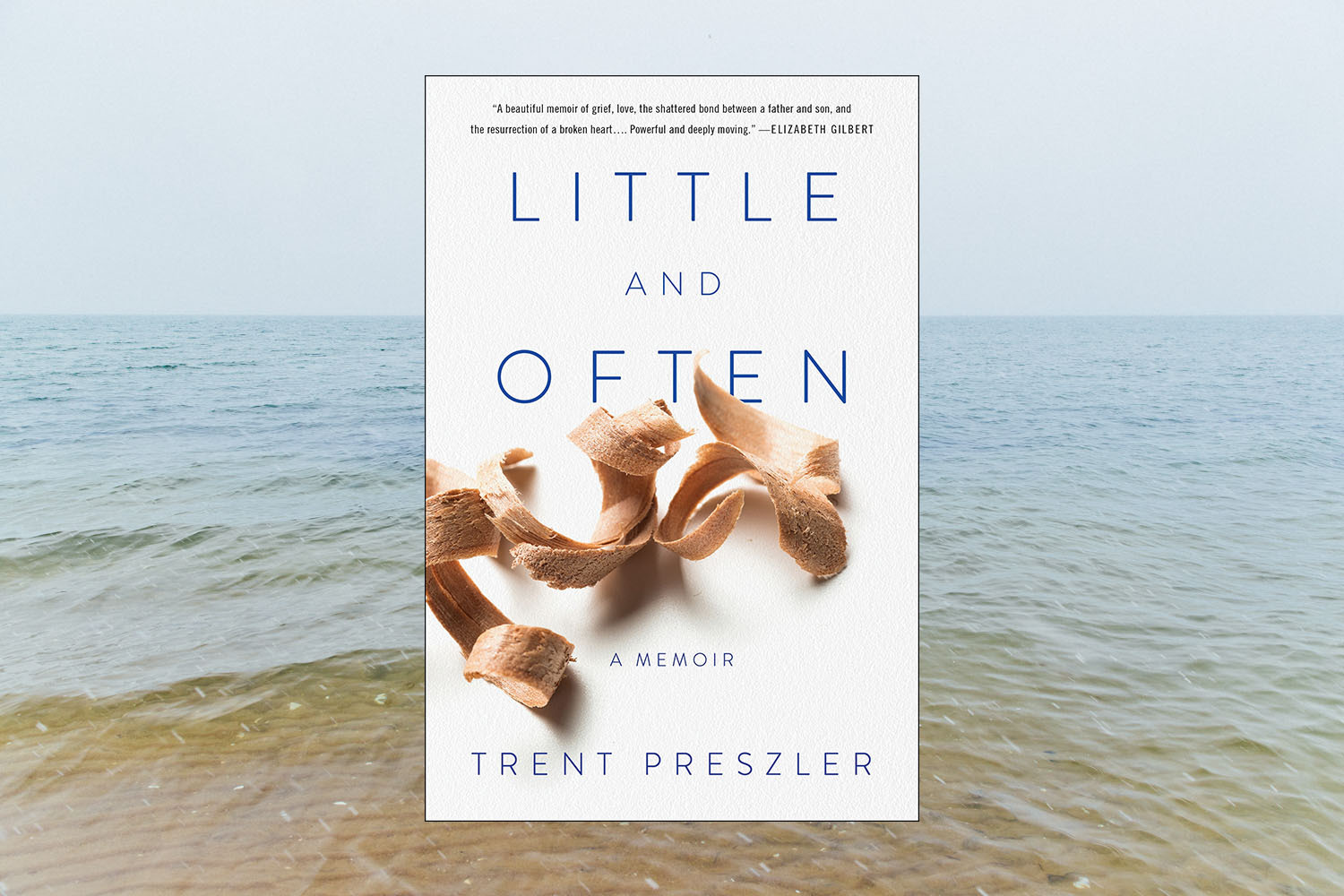

Months ago my editor told me he was itching to publish a profile on Preszler, a person making rugged yet gorgeous watercraft the old-fashioned way and then selling them for lavish sums. A few weeks later I received an email from Preszler’s PR team telling me that he actually had a memoir coming out in the spring, if I’d like to cover that.

I don’t want to write about his memoir! I thought. I want to write about his boats! It wasn’t until I read the book that I realized the two are inextricably linked: his memoir is explicitly about the events that led him to build his first ever canoe.

Little and Often tells the story of Preszler’s life, from his religious upbringing on a South Dakota farm to his life as a New York socialite and the CEO of a prestigious Long Island vineyard. When his semi-estranged father passed away (Preszler mostly attributes their distance to the fact that his extremely blue-collar, rodeo-champion, Vietnam-vet father would not acknowledge the fact that his son was gay), it drove him into a deep depression and made him question what exactly he was doing with his life. He decided to make something with the only thing his father left behind for him: a tool kit. His first project would be a canoe, which he had absolutely zero idea how to build. But as part of his bereavement journey, he went all in and built the thing, oftentimes to the detriment of just about everything else in his life.

At its logline, the book does not sound all that appealing: a man’s father dies so he builds a canoe to grieve. But as I read the book, I realized I never wanted someone to succeed at something so much as I wanted Preszler to build his boat — a fact I point out to him on our call. He laughs and says he hadn’t thought about it like that before.

The book is appealing specifically because it progresses along the parallel lines that are Preszler’s boat-building and his grief. Loss is difficult. Loss when you feel there are things left unsaid is even more difficult. Putting those things on paper for all to see is tantamount to heroism.

Just as the yearlong process to build the canoe was a cathartic process, so too was writing a book about it all. “There are definitely lots of things in the book that I hadn’t revealed before, and even some of my best friends who have read it learned things about me in the process.” Preszler says. He had to mine depths he probably didn’t want to revisit, all while continuing his day job as CEO of Bedell Cellars. “I had to dig pretty deep, and when you dig deep like that, the only natural outcome is catharsis, I think.”

Preszler points out the similarities between boat building, writing and winemaking: they are all feats of endurance, tasks that at the outset that may seem insurmountable but with steady work become achievable. He tells me it’s a tactic he learned from his father, and the sentiment from which the memoir draws its name. These days, little and often has turned into a lot and often. After completing his first canoe, which he says he will never sell because of its sentimental value, he has since sold three boats, each representing an entire year of work.

Regardless of the backstory and craftsmanship, $100,000 is still a hefty price tag. If you search for 20-foot canoes online, you’ll find prices anywhere from about $800 to $3,000 — quite the disparity when you consider they are all just things meant to convey a couple people across water. At one point in the book, Preszler’s boss from the vineyard and a prominent member of the New York art community come by to see the canoe — a rarity, since Preszler was essentially a hermit during the endeavor. They get into a debate over whether the canoe is art or an instrument. The discussion isn’t ever really settled, so I ask him directly on our call. His initial answer is a bit wishy-washy, settling on “artistic boats” without really committing to an answer.

“Let me make it easier for you,” I say, “whoever buys your next boat, would you rather them use it or hang it on their wall?” His response is quick and decisive: “I’d rather they use it, because it’s like having a thoroughbred race stallion and putting him in the stable then not letting him run.”

This confidence in his craft was probably absent during his first bout of boat-building, the one he writes about in Little & Often. “I’ve learned a lot and I’ve improved my technique and learned from all the bitterness of my mistakes. And I don’t think I could build beautiful boats now if I hadn’t made all those mistakes back in the beginning,” he tells me when I ask if he is better now than when he built the first boat.

“Every boat, it’s almost like as soon as you finish it, you want to start the next one, because you know where you messed something up or you want to just try it differently next time. I suppose it’s like writing, too. Once you catch the bug and you’re like, ‘Oh, that felt really great when it worked,’ you want to touch that magic place again.”

In reading Little & Often, it is clear that Preszler is a man constantly in search of something: acceptance, the ability to accept love, community. “A wonderful side effect of the boat was that I finally found a community of like-minded people, and for so long, I had felt like I moved to New York and didn’t fit in, and the gay world in New York is its own specific thing, and I was too gay for the country, but too country for the city.”

He says his love for boatbuilding has led him to online spaces where he’s finally found a community that works for him. “I just discovered this whole world of woodworking and boat building and DIY craft and people all over the world, who I’m now friends with on Instagram, and I’m able to share images and videos and thoughts with and bounce ideas around with, and what an amazing thing that the canoe has brought into my life, this whole realm of connection and community, which I’d never had before.” He is now a star in the boat-building community and has even struck up a friendship with Nick Offerman, who is also an avid boat builder and outdoorsman, through their mutual love of the craft.

When I ask Preszler how he would describe himself, he goes with “I’m the CEO of a winery, but I also build boats and write books.” Finally, it seems, he is confident with this description.

Little & Often is out now via HarperCollins, and available for purchase here.

This article was featured in the InsideHook NY newsletter. Sign up now for more from all five boroughs.