This is the third in a series of pieces we’ll be running all month in conversation with Helen Macdonald’s Vesper Flights, the InsideHook Book Club pick for September. You can sign up for our Book Club email to receive important updates, announcements and notifications here.

The American kestrel is often found in open habitats, with ample cavities for nesting and plenty of perches for casting its eyes on potential prey. Tending to take up residence in undisturbed natural areas, the blue-winged raptors are most often associated with Midwestern states like Idaho and Illinois. But in the Bronx, New York — where disturbances to the natural world are numerous and frequent — Alyssa Bueno, a 24-year-old birder and environmental educator, has recently spotted the tiny, freckle-breasted falcons outside her Pelham Bay Park home.

“It’s kind of crazy how we have here in New York City all these birds that are only common in what you’d consider ‘undisturbed natural areas,’” Bueno tells InsideHook, “whereas in New York we have lots of people, we have noise pollution, light pollution, all these different things that could be disturbances for birds, yet we see birds thriving here.”

On eBird, an online database of where and when birds are observed throughout the globe, kestrel sightings in the Bronx total 597. The very first of these was spotted by entomologist Frank Watson in the Spring of 1925 and the most recent (as of this writing) was logged by Alyssa Bueno on August 22, 2020.

Bueno is one of a small handful of Bronx birders — and an even smaller circle of Pelham Bay Park birders — who log their findings on eBird. She is notably one of the youngest in the group, as it’s not rare to find eBirders whose earliest logged lifers — meaning birds that are seen and positively identified for the first time — date as far back as 40 to 50 years. And while it’s clear that some older birders have since settled elsewhere, Bronx sightings remain some of the earliest checked off their lists, making the northernmost New York City borough a sort of lifer among birding regions: a place where the diversity of local wildlife is enough to turn an amateur naturalist to a serious birder.

Bronx parks like Pelham Bay, Van Cortlandt and Pugsley Creek are often regarded as bridesmaids to Central Park, where birds are in the habit of coming up to watchers at eye-level during migration season. “Central Park is amazing, but I just think the Bronx is really special in its own right,” says Bueno, a Bronx native, pointing out that this time of year is especially exciting as herons, egrets, oystercatchers, sandpipers and clovers flock to the borough’s salt marshes for fall migration.

One of the first things New York City birders will tell you is that the city lies on the Atlantic Flyway, the route used by hundreds of millions of birds to fly north every spring to their breeding grounds and back again in the fall. Van Cortlandt Park, designated an Important Bird Area (IBA) in New York State by National Audubon in 1998, sees around 200 migrating birds every year, including woodpeckers, wrens, thrushes and warblers in a variety of resplendent colors.

“There are several species that nest in the park, but there are also some that use the park as a stopover to rest and eat insects and seeds and other sources of food,” says Richard Santangelo, the program manager for Audubon New York’s For the Birds!, a place-based environmental education program that promotes awareness and appreciation of nature through the study of birds. Santangelo, who has worked in an educational role at Audubon for 11 years, says that often students who may come from other countries or have parents from other countries will feel a connection with migratory birds. “If there’s a bird that lives here in the spring or summer but migrates back to Central or South America in the winter, sometimes kids will make that connection between themselves and the birds. They’ll say, ‘Oh, that’s the country I’m from.’”

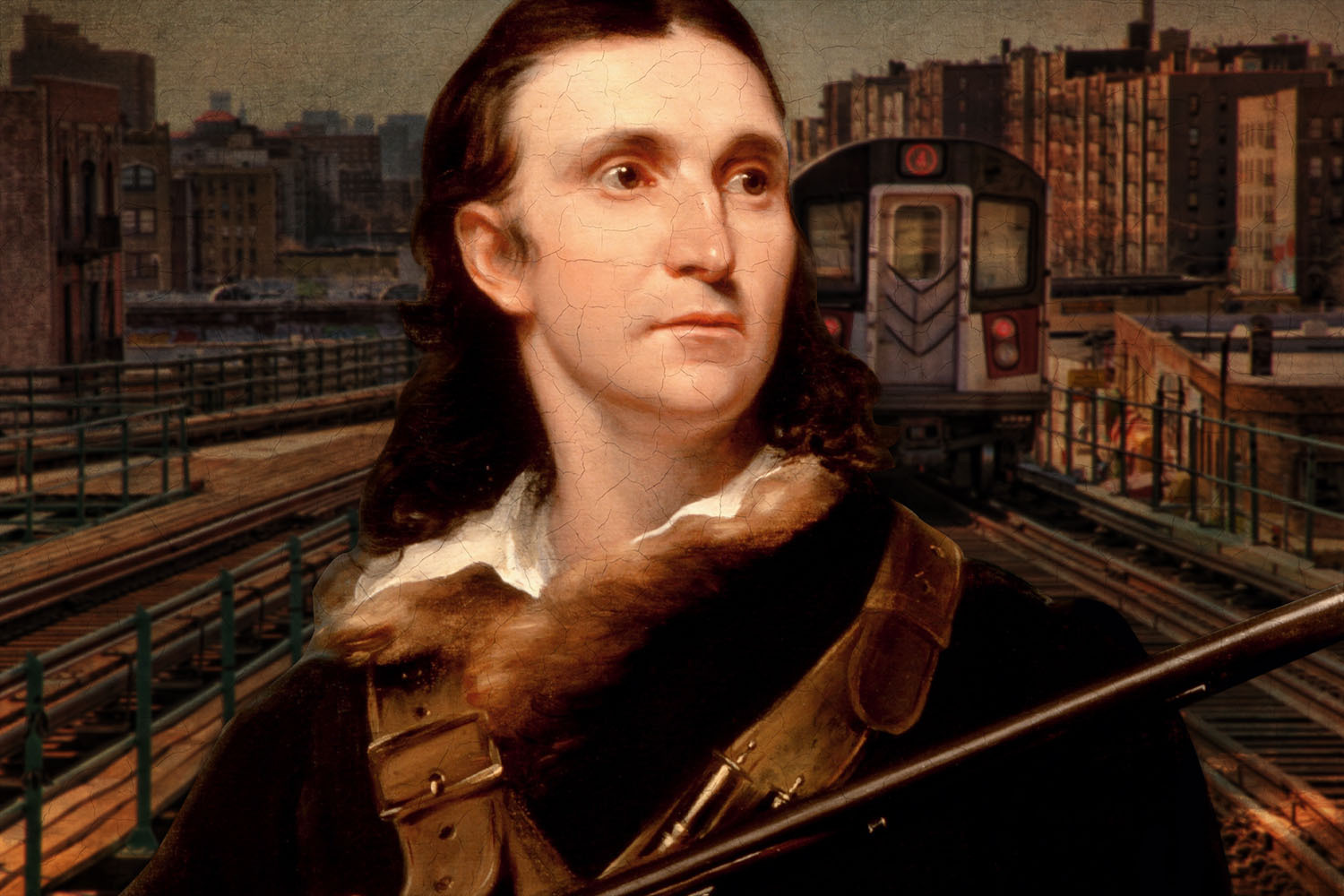

New York City’s Flyway helped it become a very important birding area long before any of its parks were designated IBAs. This is true especially of the Bronx, where parks contain a range of different habitats, including woods, saltwater wetland, shoreline and meadow. John James Audubon, the namesake of the National Audubon Society, moved with his family to a large estate in the Bronx-adjacent Washington Heights neighborhood of Manhattan in 1842. And in 1924, a group of nine teenage boys gathered in the High Bridge section of the Bronx to form the Bronx County Bird Club, or the BCBC. The competitive, iconoclastic young naturalists — as writer and scientific historian Helen McDonald calls them in her new book Vesper Flights — were responsible for volumes of findings on barn owls, peregrine falcons and more than 40,000 photograph negatives representing 400 bird species. The latest edition to the group, Roger Tory Peterson, is authored and illustrated Field Guide to the Birds, which was published in 1934 and is considered the first of all modern birding field guides.

The young men, who would eventually induct one woman, Helen Cruickshank, as an honorary member in 1937, also took part in early Christmas bird counts — then called “censuses” — finding close to 40 species, among them a short-eared owl flushed at the mouth of the Bronx River. In more recent years, bird counts have looked a lot different. In 2018, 111 participants in the field throughout the Bronx-Westchester region observed 19,119 birds from 116 species.

Among participants in 2018, the count, now one of the longest-running wildlife censuses and bird conservation efforts in the world (having evolved from a holiday bird hunting tradition in 1900), were contemporary birders who look quite a bit different from the BCBC members of yore —birders of color with growing online personalities, like Jeffrey and Jason Ward, who are Black, and various members of the Feminist Bird Club, which was founded by New York birder Molly Adams in 2016 in response to a violent crime near Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, where she often birded alone, as a do-something reaction to the new political climate.

Haley Scott, a Bronx birder who discovered the hobby while at school in Vermont, came to the Feminist Bird Club by way of an article her professor gave her on the Ward brothers. “Last spring when I came back to New York City, I wasn’t really birding as much as I’d wanted to — mostly because I hadn’t really found my flock, if you will,” says Scott, who, like Bueno, is 24. The two joined the bird club around the same time last year, led to their soon-to-be flock by a shared determination to connect with Jason and Jeffrey Ward — the latter of whom is a Feminist Bird Club member. Although both brothers now live in Atlanta, they are responsible for rousing a new generation of Bronx birders, whether by leading bird walks with Audubon or the Feminist Bird Club or through Jason’s popular topic.com documentary series, “Birds of North America,” on which Jeffrey is a frequent guest.

The series, which takes place mostly in New York City, pays homage not only to Ward’s Bronx upbringing but also the Bronx’s impeccable wealth of wildlife. The spoken shibboleth which plays over the opening credits of each six- to 10-minute episode also captures Jason Ward’s own Bronx-based birding origin story. “When I was 14, I spotted a peregrine falcon eating a pigeon on my windowsill in the Bronx,” goes the mantra. “I’ve never looked back.”

In a 2019 article in The New Yorker, Ward, who is a former Apprentice at Audubon, told a reporter, “These peregrines are really powerful fliers. They have the ability to just change their immediate surroundings. Growing up in the Bronx, that was something that I admired, and wanted to be able to do myself.”

What’s so appealing about “Birds of North America” is that Ward constantly makes connections to the human side of birding, as well as the bird-like side of humanity. On one episode, which takes place in Los Angeles, Ward discusses his experiences of “birding while brown” with Audubon colleagues Tania Romero and Raymond Sessley. When Sessley mentions that his spark bird was the red-winged blackbird, Ward responds positively, then mentions how the bird is not necessarily one that is beloved by people, including some birders. “There are sometimes bad connotations around black birds — omens, color,” responds Sessley, who continues, stating that the double-crested cormorant was once called the “N-word bird.”

Nowadays when we think of birding while Black in New York City, our minds may go to several racist or racially violent events. The incident in Central Park this past May, in which Black birder Chris Cooper was threatened by a white woman after he asked her to leash her dog, has created shockwaves in the birding community, leading to Audubon-sponsored events like “Birding While Black” Zoom conversations and #BlackBirdersWeek, a week-long series of virtual events which aimed to amplify the voices of Black people in the natural sciences organized by BlackAFinStem, an online collective of Black naturalists, whose organizers and followers include the Ward brothers, Black naturalist Corinne Newsome and Haley Scott.

By the time Cooper’s video went viral, he was not only an avid birder but also a volunteer educator in schools across New York City and the Bronx with various programs, including For the Birds! “The kids absolutely loved him,” said Richard Santangelo, who has birded with Cooper a few times. “Being that Chris taught in schools in the Bronx and Harlem, it was important for kids to see folks in this field who looked like them. Traditionally with environmental education and bird watching the demographic is white older people.”

White and old also happens to be the demographic most often associated with Audubon members, although that’s been changing more and more recently. “Our organization has been responding very positively and a lot of changes have been made with regards to equity and making sure that our company looks like the rest of the world,” says Santangelo.

Despite perceived setbacks that come with being a woman birder or a birder of color, the Bronx birding community is, at least according to newer birders like Alyssa Bueno and Haley Scott, an inclusive one, led by individuals old and young who are willing, if not raring, to share their knowledge with birders who have yet to select their first pair of binoculars.

“If you go to Pelham Bay Park for the first time and notice other people birding, a lot of people are super friendly and knowledgeable about the park and the various species that nest in or visit the park, so they’d definitely be willing to engage in conversation with other birders, especially if they’re new,” says Scott, who has been traveling to Pelham Bay less since COVID-19, opting instead to bike to some of her more local parks, like Pugsley Creek, which she’s enjoying for the first time as a birder, recently becoming the park’s top birder on eBird. Heeding Scott’s advice, I decided to trek out to the Bronx to see just how willing birders would be to engage.

And so, on a picturesque day in late August I found myself in Van Cortlandt Park at the edge of Tibbetts Meadow, surrounded by craggy cattail stalks, fuschia-colored wildflowers and a peeping chorus of goldfinches I’d mistook for a variety of melodious insects. There, among the flitting wings of what seemed like a thousand finches, I met Debbie Dolan, a Yonkers native and former elementary school teacher who has been birding and leading walks in the Bronx for decades. When I called Dolan a couple of days after our run-in at the park, she told me that she is responsible for maintaining the Cass Gallagher nature trail, named for the longtime Bronx resident and environmental activist, and the only trail at Van Cortlandt Park named after a woman.

When I ask Dolan why she does all this — leading regular bird walks, maintaining trails, removing invasive plant species — all on a volunteer basis, she answers simply, “I want to spread this passion for nature by educating people so that they can appreciate and want to protect it the way I do.”

In the Bronx, birding has taken on a new identity — or rather, a new series of identities. Birds, as Santangelo likes to emphasize, are an accessible animal. Every time you leave your home or apartment, you see birds. In the Bronx especially, birds you’d never imagine to exist in any of New York City’s boroughs find safe havens in everything from salt marshes to landfills. Owls, warblers, and falcons soar and flap across wet and grasslands, sparking people like the Wards, Alyssa Bueno and Haley Scott to take up a hobby they may never have thought was available to them. While Bueno may not have a spark bird like Scott (hers is the yellow-rumped warbler) or Jason Ward (remember — peregrine falcon), it almost seems like every bird is a sort of spark for Bueno, whose personal Instagram pays homage to the various birds she spots — more often than not these days — in her own backyard.

I think about how the end goal of Debbie Dolan’s educational efforts around birds in Van Cortlandt Park is conservation and I wonder if Bueno realizes that every time she posts a photo of a sparrow, a house wren or her backyard American kestrel, she is educating her followers, thus imploring them to protect, to conserve. Although the American kestrel is the continent’s most common and widespread falcon, populations declined by an estimated 1.39 percent per year between 1966 and 2017. If current trends continue, kestrels will lose another 50 percent of their population by 2075.

“Finding out that there are so many species of wildlife in the Bronx was a segue for me when it came to discovering that I can impact the world in a way that’s tangible,” says Bueno. There’s a cycle of conserving parks which begins with people coming to a clean park to enjoy local nature and ends — hopefully — with a lifelong desire to care for that which they love to observe. If you support our parks and make sure they’re clean and healthy, then you support the birds, says Bueno. But in order to support the birds, you first have to observe them, love them, seek to understand them.

Bueno once tweeted something along the lines of: Isn’t it crazy that we can remember hundreds of bird names on site or by call? “As a birder, it just becomes second nature,” she says. “Half the time I’m just thinking about birds.”

Correction: A previous version of this article indicated that John James Audubon lived in the Bronx. He and his family actually lived in present-day Washington Heights, in Northern Manhattan.

This article was featured in the InsideHook NY newsletter. Sign up now for more from all five boroughs.