There was a period of time, let’s say roughly 10 to 15 years ago, when Beyoncé developed a strange habit of dressing up like other legendary artists while paying tribute to them. At the 2005 Kennedy Center Honors, she came out to sing “Proud Mary” for Tina Turner in a bedazzled red mini-dress, flanked by three back-up singers in matching gold fringe — her very own Ikettes. At a 2008 Fashion Rocks fundraiser, just months before she played Etta James on the big screen in Cadillac Records, she did her best to channel the singer while performing “At Last” in a short blonde wig, long green dangling earrings and a bright yellow dress cut in a 1960s silhouette, paying homage to the green-and-yellow color palette of James’s At Last cover art. Later that year, she honored Barbra Streisand at the Kennedy Center by belting out “The Way We Were” styled nearly identically to the way Babs was at the end of Funny Girl — updo, cat-eye makeup, statement earrings and a long-sleeved, V-neck black gown. Even as recently as 2011, she sported an Afro and a glimmery disco-ball inspired dress at the Michael Jackson Tribute Concert while she tackled Jackson’s 1972 hit “I Wanna Be Where You Are,” looking like a long-lost member of the Jackson 5.

If you think about it, it’s an insanely bold move. Covering one of the most beloved songs of all time is always a daunting task because it inevitably invites comparison to the original. But doing that while also dressed up as the artist you’re covering doesn’t just invite comparison — it begs for it, daring you to find any reason why Beyoncé couldn’t be Tina Turner or Etta James or Barbra Streisand or the King of Pop. Of course, you won’t: in spite of all the gimmicky costumes, every tribute performance of hers is immaculate, showing off her own vocal versatility and nailing the essence of each artist while still, ultimately, sounding like no one but Beyoncé. Dressing up as them wasn’t the decision of some insecure artist grasping for an identity; it was a declaration, like Babe Ruth calling his shot. Even 17 years ago, just two years removed from her solo debut, she already knew what the rest of us would eventually come to realize: that she could very easily fill the shoes of any number of all-time greats, that one day decades from now she’ll be perched in the balcony of the Kennedy Center looking down at some up-and-comer paying their respects in a black leotard while they sweat through the “Single Ladies” choreography.

Of course, despite the fact that she’s one of the most massively popular artists of all time, there is an annoyingly vocal minority — consisting largely of rockists who have been conditioned to thumb their noses at any successful Top 40 pop star — that would disagree. They love to question her songwriting abilities by citing the fact that her songs often are credited to a lengthy list of co-writers, as if being able to effectively and emotionally interpret someone else’s words wasn’t an art in itself. They falsely assume that because something is popular, it must be catering to the lowest common denominator, and they have a hard time wrapping their minds around the fact that someone who performs in sexy outfits and makes music that will inevitably find its way into their lives against their will — at weddings, at the grocery store, on their Uber driver’s car radio — could possibly also be a Serious Artist. As a woman in the music industry, Beyoncé automatically has a harder time being taken seriously; as a Black woman, it’s doubly hard. How many of those same folks who consider her to be a vapid, overrated pop star, something shiny assembled by a team of svengalis to appeal to the drooling masses, rushed to go see Baz Luhrmann’s recent Elvis Presley biopic so they could revisit the incredible legacy of some hot guy who didn’t write his own songs?

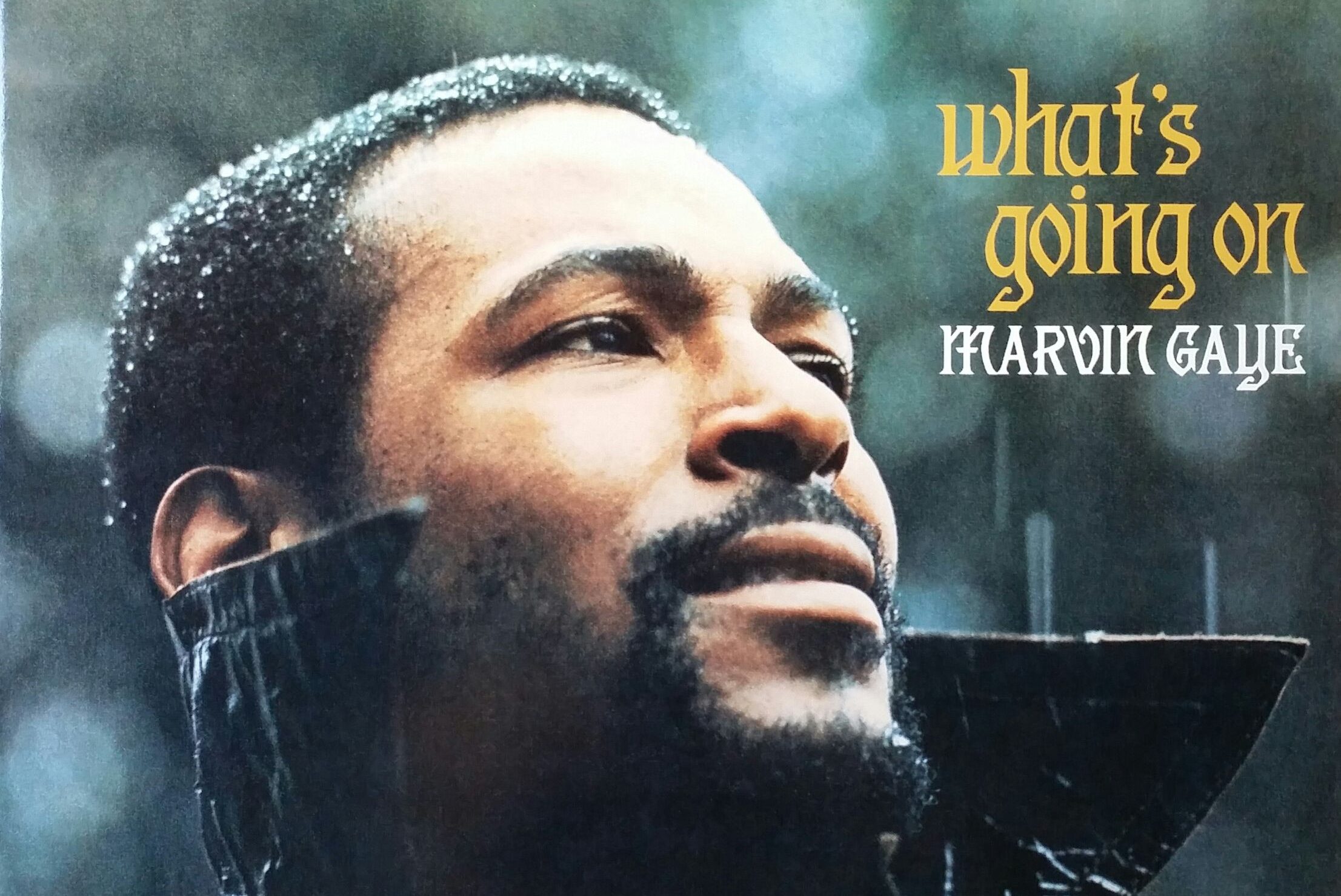

The truth is, there have only been a handful of performers in the history of popular music who were able to both churn out an impressive number of huge radio hits that’ll no doubt outlive them and become complex, innovative album artists. Those are two distinct skill sets, and while neither one is necessarily better than the other, succeeding at both is extremely rare. The Beatles did it, of course; so did Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye. Beyoncé belongs on that list, too. As a pop star, she’s been steadily spitting out massively successful singles for over two decades now. (To put it in perspective, when Destiny’s Child went No. 1 in 1999 with “Bills, Bills, Bills,” I was 11 years old. This week, Renaissance is poised to top the charts, and I’m days away from turning 34. There’s an entire generation of not-so-young adults who have spent two-thirds of their lives in a world where Beyoncé is the biggest singer on the planet.) Shockingly, there’s been no dip in her relevance; at 40, she’s arguably a bigger part of the zeitgeist than she was when she was 20 — no easy feat in a genre that places such a heavy premium on youth. But ever since she surprise-released her 2013 self-titled record, her first “visual album” that married the concept album with the music video, she’s been on a creative tear that should cement her status as one of the most important artists of her generation.

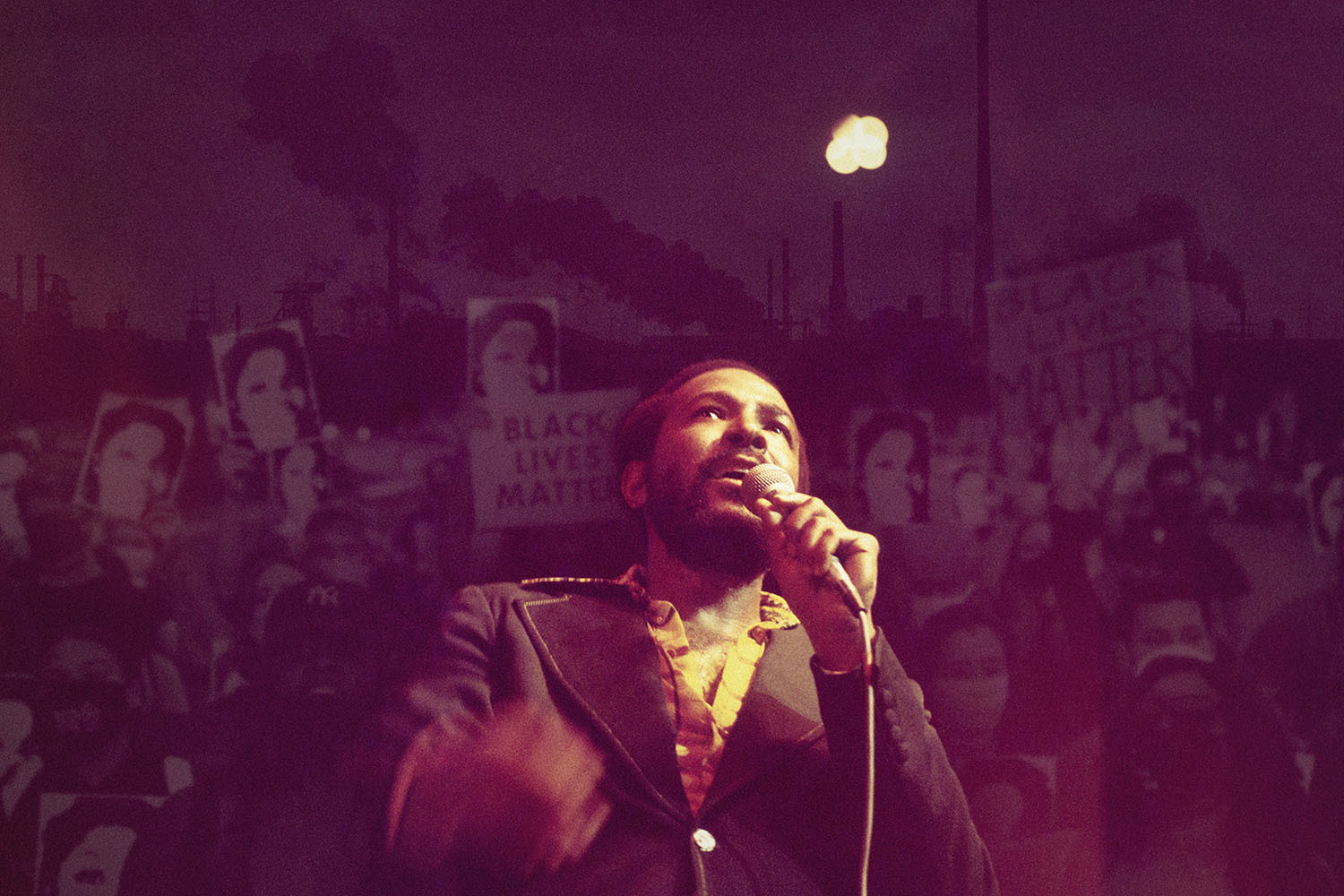

Beyoncé saw her completely changing the way albums are released while also putting out her most overtly feminist music to date. Then in 2016, she put out her masterpiece, Lemonade — a stunning visual album that saw her celebrating her “Negro nose with Jackson 5 nostrils,” sampling a Malcolm X speech where he declares that “the most disrespected person in America is the Black woman” and giving powerful cameos to some of the Black women who have been most egregiously, unforgivably disrespected, the mothers of police brutality victims Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin and Eric Garner. It was an enormously ambitious project, one that simultaneously contained her most personal and most socially conscious work while experimenting with an impressive variety of genres ranging from reggae, blues and country to rock, gospel and trap. If “Crazy in Love” was her “Can I Get a Witness,” Lemonade was her What’s Going On.

Now she’s back with Renaissance, her first studio album since Lemonade, and while it’s not as overtly political as her previous work, it still serves as confirmation that she absolutely deserves to be taken seriously as an album artist who isn’t particularly concerned with making marketable, radio-friendly hits anymore. Renaissance is a celebration of Black dance music, from ’70s disco to Chicago house, Detroit techno and New Orleans bounce. Its sequencing is flawless, each track bleeding into the next, and each sample feels meticulously chosen. Beyoncé isn’t just relying on assists from legends like Nile Rodgers and Grace Jones (who appear on “Cuff It” and “Move,” respectively); she’s using her star power to make sure we all know our history, elevating the sounds and styles of too-often-unsung heroes because she’s in the unique position to do so. She dedicates the album to her “godmother” Uncle Jonny, who died of complications from HIV, and the “pioneers who originate culture…the fallen angels whose contributions have gone unrecognized for far too long.” It’s not the first time she’s assumed the heavy burden of making sure Black culture gets the recognition it deserves — her historic 2018 Coachella performance, with its massive marching band and nods to HBCUs, is the perfect example of that. But if anything, Renaissance is a reminder that Beyoncé herself absolutely deserves to be counted among those “pioneers who originate culture”; even when she’s dressed up as someone else (whether literally in costume or offering a more subtle sonic homage), she finds a way to remind us all of her own undeniable talent.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.