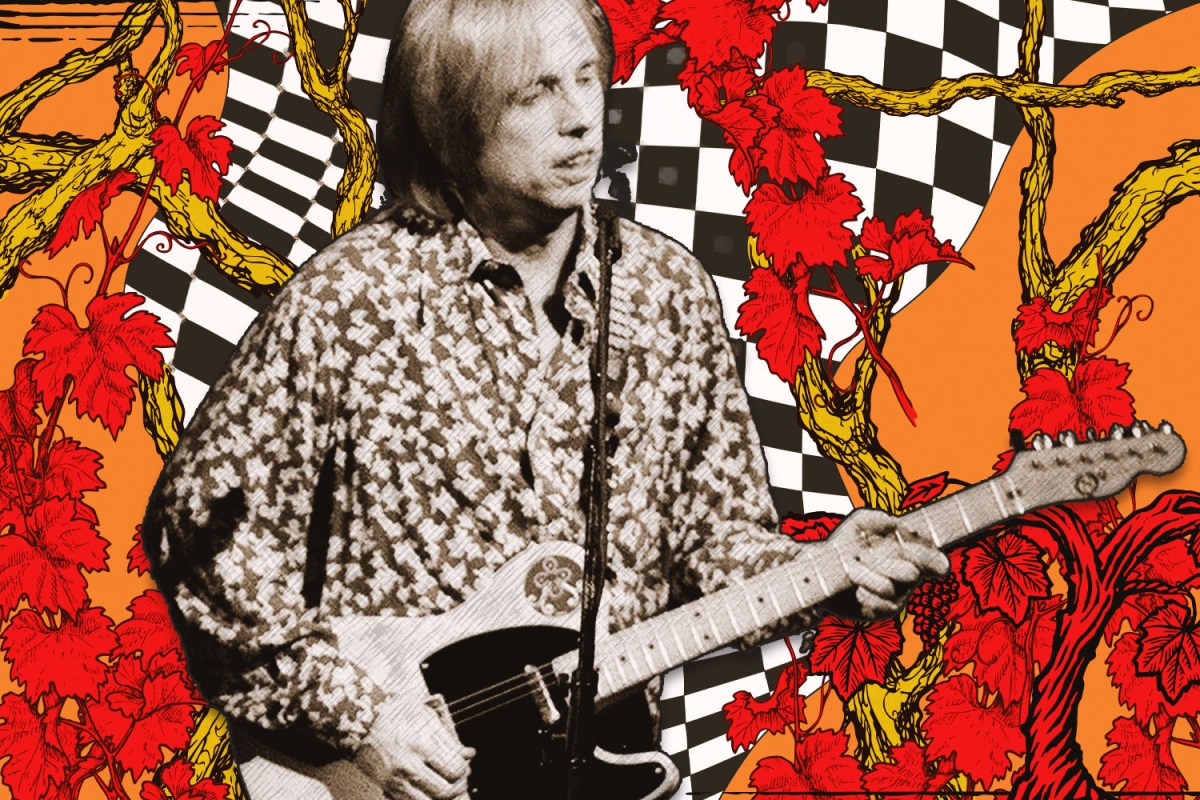

By 1997, Tom Petty was already a certified legend. Twenty years into his storied career, he’d conquered FM radio with hits like “American Girl,” “Breakdown” and “Refugee”; brought down the house at both Live Aid and Farm Aid; toured the world with Bob Dylan; embraced MTV in a big way, making a host of new fans along the way with arresting videos for songs like “You Got Lucky” and “Mary Jane’s Last Dance”; joined his friends Dylan, George Harrison, Jeff Lynne and Roy Orbison in the Traveling Wilburys; and released two career redefining solo albums, Full Moon Fever and Wildflowers.

But scaling such creative heights inevitably causes burnout. As the end of the decade loomed, Petty and the Heartbreakers had been on the album-tour-album-tour hamster wheel for so long, they weren’t quite sure what to do next that they hadn’t already done before, or what would get their collective creative juices flowing the way they had so easily in the band’s early days.

A new archival release, Live at the Fillmore (1997), answers the question. Petty and the Heartbreakers had taken up residency at the fabled San Francisco residency managed by the irascible promoter Bill Graham, and, across 20 nights, got back to doing what they did best: Playing long sets of (mostly) songs by other artists that they loved, that challenged them or were just plain fun to play. There are several versions of the gorgeous-sounding release, featuring unique versions of some of Petty’s best-loved songs, as well as loads of covers by everyone from Little Richard to The Byrds to J.J. Cale and more, but the 58-song deluxe vinyl set is definitely the one to pick up, as it transports the listener back to that tiny room, when Petty and company had the time of their lives, rediscovering what they loved about being a band, and, most importantly, friends.

Below, in an intimate conversation recalling those days, the Heartbreakers’ keyboardist Benmont Tench recalls what made his band, and most especially that month in San Francisco, such a wonder and a joy.

InsideHook: So tell me how playing the Fillmore — a tiny room by the Heartbreakers’ standards — happened. I know it was about getting back to being a band, but do you remember what led up to it? Because, at first, there were, I think, 10 shows put on sale, which sold like hotcakes, and that eventually grew to a run of 20 shows in all. But what was going on internally in the months leading up to it?

Benmont Tench: What I specifically remember is that we were putting out She’s the One, the soundtrack, and when I talked to Tom, what he understood was, “Look, She’s the One is nice, that was a fun experience, there’s some great songs left over from Wildflowers on it, and there’s some great new songs and covers, but it’s a scattershot album, and it’s definitely not the follow-up to Wildflowers, which was a serious piece of work.” So, he didn’t want to tour it. Nobody wanted the tour it. Because that makes it the record. But Tom really wanted to play, and the rest of us always really wanted to play. And I suspect it was his idea to go play the Fillmore. And, as you said, we put some dates on sale and then it turned, into, “Let’s do 20 and stay for a month!” I think it turned into that pretty much right off the bat. It was kind of daunting, because are we going to really learn all these songs? Is [drummer Steve] Ferrone really going to learn all these songs? Because he had only been in the band for a couple years. The first time we ran “Refugee” with him, for the Wildflowers tour, his reaction was, “What’s that?” Understandably so. And by that point, we had so many songs. But pretty quickly the idea for the show became something else, and it turned out he had a lot of knowledge of a lot of the covers we were choosing, because we’re the same age and we grew up during the same explosion of music. So, at that point, it became, “I know Ferrone’s got this. This is going to be a blast.”

And there were only a couple of rehearsals, I recall you telling me once.

I seem to remember there were three, but maybe there were five. Somebody said there weren’t any, but there were some. We went to some soundstage, or some rehearsal room, and we just we just played whatever Tom called up. So, we had a basic structure, and then we were off to the races. We’d play a few hits now and then, because Tom thought there was a great importance to a proper set order that builds, to go to the right places and comes down in the right places and has a good finish. So, he came up with a good structure, but the structure was emotional rather than fixed. So, there was a lot of continuity between shows, but boy, there was a lot of stuff that wasn’t the same at all. And it was great fun.

And how did it evolve over the course of the 20 nights, as a band? From the stage, what did you notice within the band? Did it evolve or change in any surprising ways?

Well, we relaxed. We relaxed into anything that happened. And this wasn’t an entirely alien concept to us. Early, early on, Tom would call more audibles. And he’d still do it on occasion. With Bob Dylan, for instance, he would often play things a little bit different. He didn’t throw things out the window and completely fuck them up all the time, the way people think. But he would do songs a little bit different, because how else is he going to keep them alive? So, to have 20 nights where you go, “Okay, we’re going to do it different,” we were just going to have fun, and, for the first time in a very long time, we we’re going to play a small, theater-sized club. And this was the first time we did it. We went back and did it again. But this was the kind of the granddaddy of them all.

Were there any real trainwrecks, and were you able to kind of laugh them off, because you weren’t playing to 22,000 people?

We always wanted to be really, really good. There was never a night when we didn’t want to be really, really good. But also, you can’t take yourself too seriously. If you blow a stop or you below a change, you can’t take yourself too seriously, because the minute you let that get to you, then the rest of the song goes to hell.

The rest of the set goes to hell.

Yeah. So, I’m sure there were trainwrecks, but I can’t specifically recall any. I know that the turnaround in “Hip Hugger” was a trainwreck, because I was, like, one note off both times it came around, and the rest of the band is just going through those beautiful smooth changes. And I’m the lead instrument! So, that was, like, “Whoops!” But as far as a real trainwreck, I doubt that there were any. I mean, when we played “Gloria,” we’d played that a few times, I’m sure, but we just played it off the top of our heads. And you can hear on that, when Tom sings, “And the wind started calling her name,” we didn’t coach the audience. They just started singing “Gloria” quietly, and got louder and louder and louder. That’s not something that you plan for in rehearsal. And he wasn’t standing there going, “Come on, everybody sing!” None of that. That’s the stuff that you can only get when it’s being called forth. That’s what you want.

Sowing the Seeds of “Wildflowers,” Tom Petty’s Not-Quite-Solo Album

Petty always said his solo projects were essential to the survival of the Heartbreakers — so much so that his 1994 masterpiece bloomed into a group album in all but nameI want to give props to each of the players individually, because this is a really special version of the Heartbreakers and what they can do as individuals and collectively. We already talked about how important Ferrone was to this experience, so let’s start with Mike Campbell, who plays his ass off throughout.

Oh god, yes.

I mean, it’s just crazy.

It’s kind of easy to take Mike for granted, because, since the day I met him, when he was probably 20, he’s been like that. But he’s putting his heart into every note. It’s remarkable. If you just listen to this stuff and focus on just Campbell for a while, Jesus. And, just to get back to Ferrone for a second, he’s swinging beautifully. He’s just swinging like son of a bitch. And he’s putting these little things in there that move things along. Ferrone plays beautifully on this whole set. And some of it’s on this little cocktail kit, though most of it’s in the big kit.

There’s moments in his playing that really elevate the songs.

Yeah, which is really, really cool.

Talk a little bit about Scotty Thurston and Howie Epstein, because they’re the utility guys who never quit, and they really add a dynamic, both of them, that’s really important to these recordings, I think.

Well, we knew Scott was just a terrific all-around musician. So, pretty immediately, it was like, “Hey, why don’t you put on guitar?” And he was a terrific singer, so then it was, “Hey, let’s get Howie and Scott singing together!” And Scott, as a singer, was indispensable, especially after we lost Howie. And also, Scott is such a beautiful person as a musician. He’s a wonderful piano player, which he never got to do on stage. He is a stellar guitarist, and a spectacular harmonica player. And so, all this subtle stuff, that you might not notice immediately, was essential to the sound of the band, and essential to being able to pull some of these songs the way that Tom wanted to pull them off. A lot of people think, “Oh, yeah, Scott, he was in Motels.” Yes, and before and after that, he played with Jackson Browne and Iggy Pop and the Ike & Tina Turner Revue! Superstar.

Funnily enough, Howie was the first Heartbreaker I ever met. After Ron Blair [the original Heartbreakers bassist] left, he really took that job to a whole other place. And by 1997, he owned that space on the stage. I know that’s something we agree on.

Howie, on this record, is lovely to listen to and play bass. For one thing, it’s lovely to listen to him choose, like, “Okay, at long last, I can play somewhere up on the neck during ‘Good to Be King,’” because he suddenly felt some freedom in what he was doing. The choice of that, the little movement in the lines, and to hear the utterly uncanny way that he sings with Tom, is the reason Howie gets so many props, as he should, as a harmony singer. The tone of a singer’s voice when they harmonize with somebody else is crucial. Howie had it in spades when he sang with Tom. We were blessed. We were so fucking blessed to have Howie and Scott. So, there was nobody just hanging around up there trying to figure out, “What am I going to play on this song?” There was none of that. Everybody was a crucial member of the ensemble. And everybody stepped up.

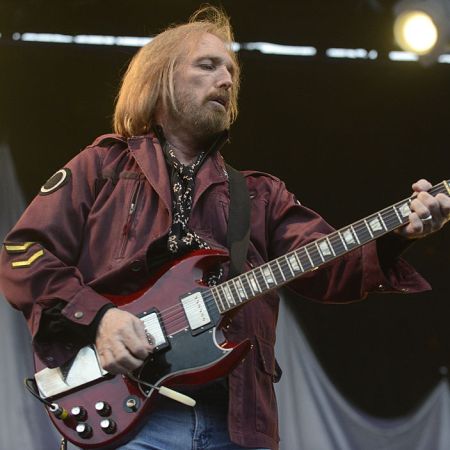

Everybody was such an integral part of the unit, and they really deliver in such unique and individual ways on this album. But, of course, without a great frontman, without a great captain up front, it’s just a great band playing great music. But Tom is the guy remembering all those structures, all those lyrics, keeping the audience interested — which, even in a small venue, is still a challenge, especially because by that time he was used to working big audiences — it’s all so remarkable to listen to. Talk a little bit about your memories of Tom from these shows and how he delivered.

Well, the great thing is that I first I saw him across a music store; I didn’t know his name, but he was one of the older kids at the music store I hung out in. And then I went to see Mudcrutch a couple of years later, and he was the bass player and one of the singers. And then I joined Mudcrutch, and he was a guy who I really looked at, who I really looked up in Mudcrutch. And so I got to see him become the front guy. It happened in plain sight, how great he became as a band leader, and at keeping the band together, for that bloody long. And the thing about him fronting the band, he knew how to pace the show. He knew how to hold an audience’s attention. He got to be funnier at the Fillmore. I think he was a little bit looser. He was cutting up more. And he’s having these ideas for covers and he’s being a ringleader when Roger McGuinn and John Lee Hooker and Bo Diddley come on. And he’s approving anybody that they throw up as opening act, anybody who wasn’t his idea. He’s doing all this and being a terrific band leader.

We were an instinctive band. We rarely needed him to say, “Let’s break it down here.” But he knew how to be the focal point that conducted all of that without saying or doing anything, so there’s all of that, which is just remarkable in a band leader. And he wrote “American Girl” and “I Won’t Back Down” and “Free Fallin’” and “Refugee” and “Running Down the Dream” and “Even the Losers” and “Breakdown” and “Wildflowers” and “You Don’t Know How It Feels” and “Echo.” He was a motherfucker. He put his heart and every song. He was completely present in every damn song. For some reason, it was easy for Tom to fly under the radar for a lot of people, but to not recognize that this guy is one of the best rock and roll songwriters that the country ever produced. Period. A terrific singer. A badass guitar player. And a bandleader beyond parallel. Did I take it for granted? I was very appreciative. But hearing the recent box sets, and especially this live stuff, and listening to it all run together, the appreciation I have for the whole damn band, but especially for Tom, just grows every time I pay attention. He was the shit. And this is one of the cases where we — unlike in arenas, where we play basically the same set every night — got to really stretch. “We’re really going to do this?” I mean, be still my heart! I mean, we knew how to do it, but we hadn’t done it in a while, and we’d never done it with the eyes of the public on us, and we’d certainly never done it a legendary place like the Fillmore. It was like, “Fuck yeah, we’re going to do it!” And we did it great. And Tom, you know, I mean, I disagreed with him on all sorts of shit. And I’m sure I was a pain in the ass. I’m sure sometimes he totally thought, “Oh, shut up Ben.” But we were in a band together. And damn, did it work. And damn, did he know how to make it run.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.