If you’re a music fan with a working internet connection, you’ve no doubt already heard that earlier this week Rolling Stone published a new version of its 500 Greatest Albums of All Time list, this time making more of an effort to include women and people of color on a list that, when it was originally published in 2003, consisted mostly of works by white, male rock musicians.

As you might imagine, this has sparked plenty of debate, angering rockist Boomers and causing cynics to question whether certain albums made the cut because they’re really that great or because they happen to be made by someone who isn’t a white man. (The answer is yes, they are that great, but also, music’s not a contest, and lists like these are always going to be subjective and designed to generate clicks by pissing people off.) But if anything, the outrage illustrates the absolute futility in making “greatest of all time” lists; attempting to attach numbered rankings to albums spanning a variety of genres across the entire history of recorded music is downright impossible.

Is Harry Styles’ Fine Line (#491) really better than Bonnie Raitt’s Nick of Time (#492)? Is Pet Sounds (#2), which famously was influenced by the Beatles’ Rubber Soul (#35), better than every record by the Fab Four? How do you even begin to compare something like Britney Spears’ Blackout (#441) to Alice Coltrane’s Journey in Satchidananda (#446)? Beyond that, what even makes an album “great” for the purposes of a list like this? Are fantastic songs enough, or does it need to carry historical and social significance as well?

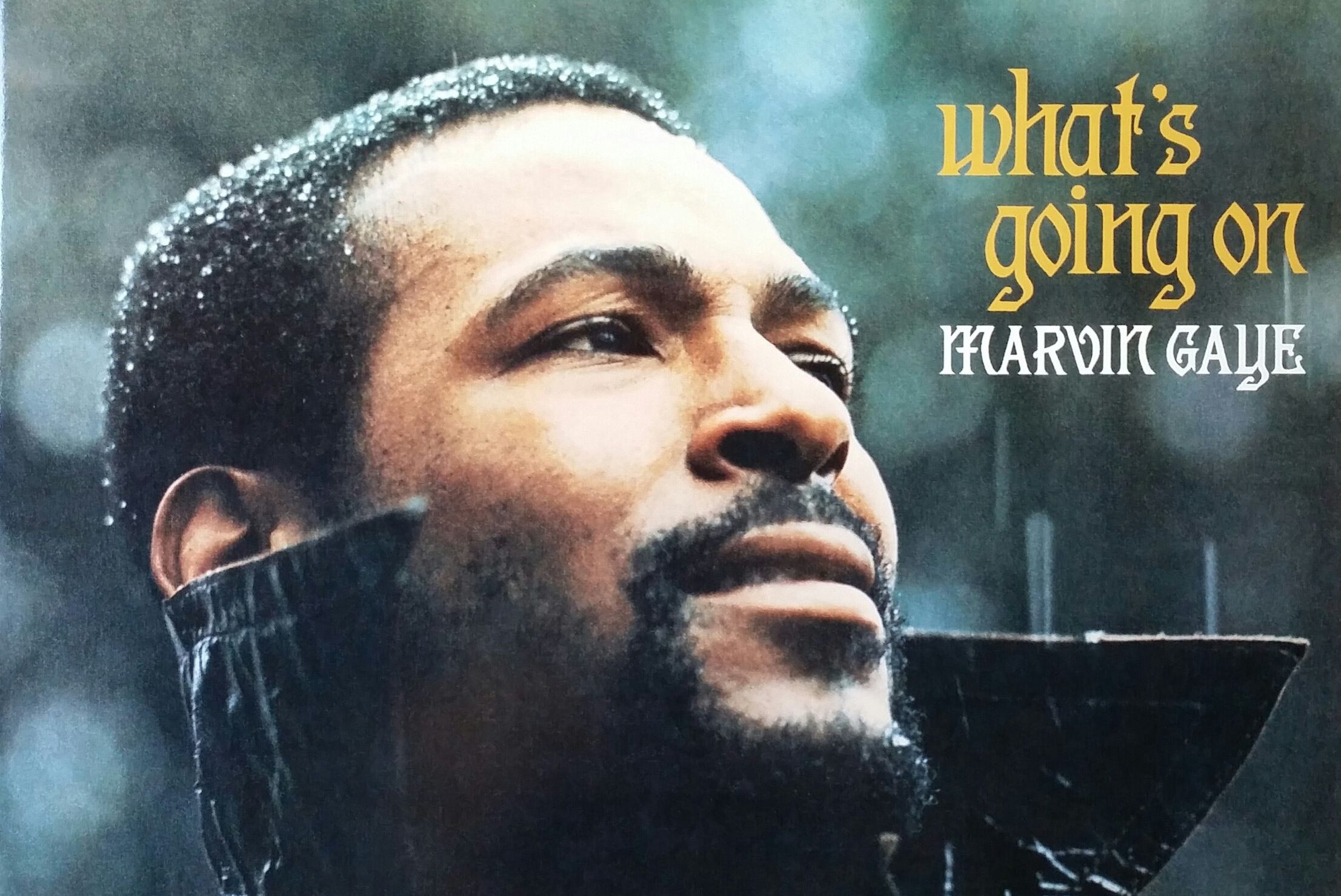

To be fair, all of the albums that made the cut are excellent listens, and plenty of the changes to the list are welcome improvements. Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On — a masterpiece whose message sadly is just as relevant today as it was when it was originally released in 1971 — rose from No. 6 on the original list to the top spot. The top 10, which originally included four Beatles records, two Bob Dylan albums and not a single work by a woman, now includes Joni Mitchell’s Blue (#3), Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours (#7) and Lauryn Hill’s The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill (#10). There are approximately three times the amount of hip-hop albums on this year’s list than the original, and genres like Latin pop and krautrock make their first-ever appearances on the list. Artists like Bob Dylan, the Beatles and Neil Young are still heavily represented (with nine, eight and seven albums apiece, respectively), but now six Kanye West albums are present as well.

And to be clear, the numbered rankings are supposedly reflective not of an arbitrary decision by a group of editors, but vote tallies from the more than 300 ballots from journalists, musicians, producers, label heads and other industry figures. (Although my years at music publications putting together similar year-end best-of lists give me pause about whether the list we see is actually a result of raw votes; most likely those results served as a jumping-off point for editors to make adjustments.)

“One distinction from the old list is the idea that there’s not one objective history of popular music,” Rolling Stone’s reviews editor Jon Dolan, who oversaw the list, explained in a post about the publication’s methodology. “I think it’s an honest reflection of how taste is now. It’s not a pure rockist perspective. It’s more about different histories existing together, a coalition of tastes.” But if that’s the case, why include numbered rankings at all?

Of course, the fact that we’re talking about this at all means that a “greatest of all time” distinction isn’t totally meaningless. Arguing over whether one of the greatest country albums of all time is better than one of the all-time best electropop records makes no sense whatsoever, but the list has sparked some interesting debates about certain artists’ catalogues. (Is Abbey Road really the best Beatles record? Does Lemonade deserve to be ranked above Beyoncé’s self-titled?) And if anything, a massive list like this can be a means of discovery — both for young music fans looking to dive into the essential listens that came out decades before they were born and older fans who maybe aren’t as plugged in to the current music landscape as they were decades ago. Whittling down the entirety of music into a list of the 500 “greatest” is impossible, but if it gets even one person to pick up an album they wouldn’t have otherwise heard of, it can’t be all bad.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.