Richard Hell doesn’t like being called a punk. It’s surprising, considering he’s remembered as a punk innovator. He’s a man who defined New York’s 1970s CBGB era, influenced the Sex Pistols and was a member of some of the greatest punk bands of all time: Television, The Heartbreakers and The Voidoids — before walking away from it all. But he’s sure: “I’m not a punk.”

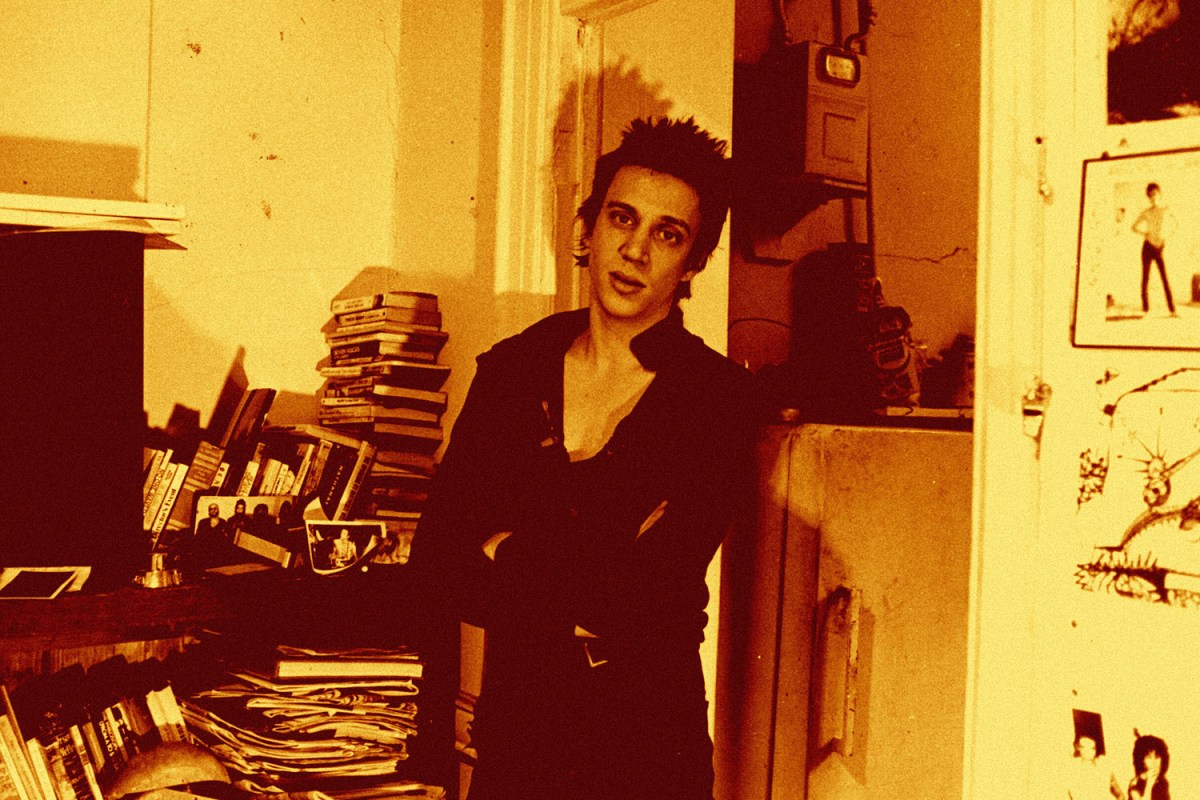

Speaking to InsideHook from his home, Hell is an introspective person. He has already lived three or four different lives outside of music, having arrived in New York as a poet, then a publisher, an author, an actor and a film critic. He has even directed a short film. But it’s the records where he solidified his status as an icon: that skinny, bare-chested frame on the cover of Blank Generation, the hazy, mischievous glare — tired after weeks, maybe months, of shenanigans. And his singing, which was more playful and debonair than his growling punk contemporaries, set him apart.

Earlier this year, Hell released the third and final remix of his second album with The Voidoids, Destiny Street: Remixed. It marks the end of his journey with the original 1982 record, produced just before his retirement from music. Over a Zoom call, we discuss poetry, cinema, his entry into New York City’s CBGB era, what “punk” means, his regrets and much more.

I’ve been a fan since I first heard Blank Generation. It’s strange to meet you over Zoom.

Richard Hell: It beats just audio for relating to people. I don’t use it that much, but I tried attending a poetry reading using it last week and I really dug that. It was a tribute thing, so four or five people were on the screen at once, and it was fun to watch everybody’s facial expressions. I never liked going to physical poetry events much. You can’t slip out so easily.

You wanted to be a poet yourself when you first moved to New York.

I hated school. I kept getting in trouble. Me and my friend Tom [Verlaine of Television] ran away to Florida to become beachcombing poets together. But the police caught us and sent us home. I decided to go on my own to New York. I was 17, and it seemed to me Dylan Thomas had had a pretty good life. At least I thought I was as good-looking as him. I started a poetry magazine and bought a tabletop printing press. This lasted four or five years. I got impatient and felt isolated. I wanted more interaction. I wanted to make myself heard, and that wasn’t going to happen with poetry. I was ignorant, but I do still love poetry.

Do you remember your first apartment in the city?

I arrived without money and got a job as a stock boy at Macy’s. I didn’t have any place to stay, so one of the guys from the stock room agreed to share his room with me. It was tiny, the kind of place where legally it was one person allowed. You could touch all the walls from the bed, which we had to share. The guy would come home drunk and vomit in the bed. That lasted two or three months before I saved up enough for my own place.

What was so special about New York at that time?

It was easy to get a part-time job, pay for an apartment and have plenty of free time. Tom came up to the city pretty soon. The New York Dolls inspired us first. Tom liked Jonathan Richman more. But they were street kids like us and like the poets I hung out with. They took initiative by starting a band and creating a following. Before that, the idea of making a record was inconceivable. But seeing the Dolls do it was a demonstration. If you take the initiative, you can do it yourself, which is the tradition I came from in poetry. Rather than wait to be discovered, do it yourself. So I said to Tom in 1973, “Let’s start a band.” We were called The Neon Boys, the precursor to Television.

Among the many lives you’ve lived, you were a film critic. What can you tell us about that?

I worked in a shop called Cinemabilia in the early ’70s. It was the longest and last job I had before music. It sold books about film and film posters and scripts and stills. Tom came to work there too, after a while. The guy who managed the store, Terry Ork, basically enabled Television by letting us rehearse in his loft. I’d always loved movies, but I got real knowledge at the store. I wrote film term papers for students at Columbia, 75 bucks a pop. Yeah, so, much later, back in the 2000s I took a job doing a film column for BlackBook magazine.

You’re known as a punk pioneer. But you don’t strike me as “punk” in the way, say, John Lydon does.

Yeah, I never liked punks. When I was a kid, I remember going to see the movies in my hometown of Lexington, Kentucky. There would always be a few obnoxious teenagers who would start throwing popcorn and yelling, ruining it for everybody else. That was punk behavior. Lydon is an interesting case. He’s obnoxious and intolerable. It’s all about himself, similar to Trump. But he somehow transcends it. It’s interesting. There’s something poignant about him that you have to love. He’s tortured and appears to have some honor, substance and loyalty about him. But at the same time, he has that punk thing where he’ll just try and get under your skin, do anything for attention and blatantly lie while calling himself the only honest one. I’ve always preferred that people respect each other.

What was it about Destiny Street that had you return two times?

I was so dissatisfied with the original. I only made two records, and the second, Destiny Street, had good material and very good musicians, and I felt I’d blown it in ways I thought could be repaired under the right circumstances. It’s commonplace for artists to remix their work now. After the original release, I felt remorse immediately. I was in bad shape from drug use and neglected my responsibilities with the album, and it showed. I left music shortly after. I wanted to remix it, but the record company lost the tapes, so I just had to live with it and try to put it out of my mind.

How did the 2009 Repaired happen?

In the early 2000s, I found a cassette tape we made during our recording, of only the rhythm tracks — no solos, no vocals. It was very clean. The original had too many guitars overlaid and sounded like sludge, like a thick storm of static. The clean, clear cassette became the only chance I had to improve the album. So I sang again. Quine, my glorious guitarist, had agreed to add the solos. But he died before I went into the studio, so I got the best possible replacements — admirers and friends of his who were top players. I felt that the 2009 Repaired succeeded. Even though Quine was missing, the songs were better served. And it was fun. I always intended to eventually release the two versions together. And I thought that was the end. I would move on.

You didn’t. What brought you back to make this year’s Remixed version?

Two years ago, someone found the original 24-track tapes. It allowed me to do the remix I wanted to do. Now it’s the definitive version. I really like it, and I feel like it’s everything it could be. The Complete has all three of the versions, plus 10 or 12 demos made between Blank Generation and Destiny Street. Interested parties are glad to have all three-plus versions in one place, but the important one is the Remixed. The full two CDs are a bizarre collection. But the whole theme of the album was time, so it makes sense that way too. The best song on the record is “Time,” and the title song is about a guy meeting himself as he was in the past.

I love the original Destiny Street. Can you still see the merit in the first recording?

That’s what I always hear. People say, “But I liked the first one!” It’s almost inevitable that if you’re familiar with a version of a song you like, another similar version will sound wrong. For me, the original album is still difficult to listen to. When I got the rights back 15 or 20 years ago, I deliberately let it go out of print and refused to license it again. There’s absolutely nothing to prefer about the 1982 version except that it’s part of a story, the story of Destiny Street Complete. But the clarity and power of the remix is clearly preferable.

What was it like returning to the studio after all these years?

I love making records — just no other part of being a pop musician. Except maybe some of the incidental perks. Every once in a while I can get wistful that the 200 more songs that I would have created if I kept at it don’t exist. I don’t like the rehearsing, touring, interviews … But I like being in the studio. I had a fantastic time for 12 days in the studio with Nick and Erin. I like creating recorded songs. Only you can’t do that as a livelihood without all the rest.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.

![[L-R] Bill Berry, Michael Stipe, Mike Mills and Peter Buck of R.E.M. at the Aragon Ballroom in Chicago, Illinois on July 7, 1984.](https://www.insidehook.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/rem-book-interview.jpg?resize=750%2C750)