“When we visited places, we were affected by that, and what was going on there, as well,” says guitarist Mick Jones of what drove the creativity of his band, the ever-touring Clash, in 1982. “When we traveled, our experiences broadened, and we brought what was going on around us into the music. And for me, New York City was really happening at that moment.”

While most people consider The Clash’s 1980 3-LP opus Sandinista! its “New York” album — what with its expansive blend of old-school rock and roll, rockabilly, funk, hip-hop and even a sprinkling of jazz — it’s really Combat Rock, which turns 40 this week and is being feted in a lavishly expanded form, that was truly born of the band’s adventures in the “city that never sleeps.”

“In every town we went to, we’d get out and about, and in conversation ask people, ‘Well, what’s happening in this town?,’” bassist Paul Simonon recalls. “They’d tell you, ‘It’s crap, there ain’t no clubs here.’ Or, ‘This place is good, and you should check it out.’ By being informed in that way, we’d discover a lot more about the town. That was our situation in New York, where we met people like [the graffiti artist and rapper] Futura and got informed. We were open for information.”

Though work on the album began in London at the end of a tumultuous 1981 — a year that saw The Clash bring New York’s Times Square to a standstill during its 17-night residency at the dance club Bond’s, making the national news in the process — it was the experience of setting up home base in New York City in 1980 and ’81 that would inform the songs on Combat Rock.

And so, “Overpowered By Funk,” “Sean Flynn,” “Car Jamming” and “Ghetto Defendant” — a long-circulated but nevertheless remarkable alternate version of which appears on the expanded Combat Rock, sporting the English Beat’s Ranking Roger toasting over it, no less — could not have been written without the band’s experiences with downtown’s flowering post-punk New Wave scene, not to mention the hip-hop explosion they, and most especially Jones, had witnessed firsthand in the Bronx.

“If you look at it, from the get-go, from the amazing first album right through to Combat Rock, we’ve got Give ‘Em Enough Rope, we’ve got London Calling — double album — Sandinista — triple album — and then Combat Rock, and in between that, touring nonstop, these guys were on a roll, man,” marvels band intimate and filmmaker Don Letts. “That’s a seriously creative roll, especially since they were always incorporating new sounds, mostly from the street, especially on Sandinista and Combat Rock.”

The band had evolved from the punky reggae party Letts had introduced into the punk scene as the DJ at London’s legendary Roxy club back in 1976 to a punky hip-hop party, courtesy of Grandmaster Flash, Kurtis Blow and others The Clash would tap as opening acts, much to the chagrin of their unsuspecting fans.

“It was a crucial time,” Letts recalls. “Hip-hop was about to break out, hence them having those acts supporting them. Having said that, it didn’t go down too well. But hey, the people would get hip later.”

Meanwhile, Joe Strummer’s “Know Your Rights” was a timely, and sadly prescient, play on what The Clash’s frontman saw as the unfulfilled promise of the U.S. he loved so dearly — and a dose of full-throttle rock and roll, matched only by the timeless Jones-penned “Should I Stay or Should I Go.”

“Pete Townshend wishes he’d written that one,” Kosmo Vinyl, The Clash’s PR man and self-styled consiglieri says. “What can get forgotten in talking about The Clash is how much they loved rock and roll and rhythm and blues; the old stuff. They loved that shit. People imagine that we were only listening to this heavy-duty stuff, but no. They just loved that stuff. They liked to play that stuff. In a band, you can forget that people are in a band to play because they enjoy it. And ‘Should I Stay or Should I Go’ was just a classic piece of rock and roll or R&B. I doubt there’s anybody in a rock and roll band that hasn’t kicked themselves over that one.”

“Because we’d come from a communal scene, we were used to building things from out of our community, and that’s what was happening in New York at that time,” Jones recalls. “Joe looked at the graffiti artists, and I was taking in things like breakdancing and rap.”

“Well, that’s the nature of the creative process, you make something and then the next step is to make something again that doesn’t repeat what you’ve done already,” adds Simonon. “That’s the creative process in my mind.”

But, of course, it’s “Rock the Casbah” that Combat Rock is most remembered for. Laid down by the band’s drummer Topper Headon — “He’d arrived at the studio early and no one was there, so he recorded that by himself,” Vinyl recalls — it catapulted the band into the big leagues of the U.S. Top 10 singles and album charts and earned them heavy rotation on the then-all-important MTV, courtesy of a fantastic video by Letts complete with tongue-in-cheek politics.

“The thing about MTV is that they didn’t change anything about what they were about to accommodate this new means of getting music across,” Letts insists. “They just did their thing. And what captures you is their performance. Back in that day, we worked on one-camera budgets, but if I’d had four cameras, I could have done that in one take. When those guys did their thing, man, they were like four sticks of dynamite.”

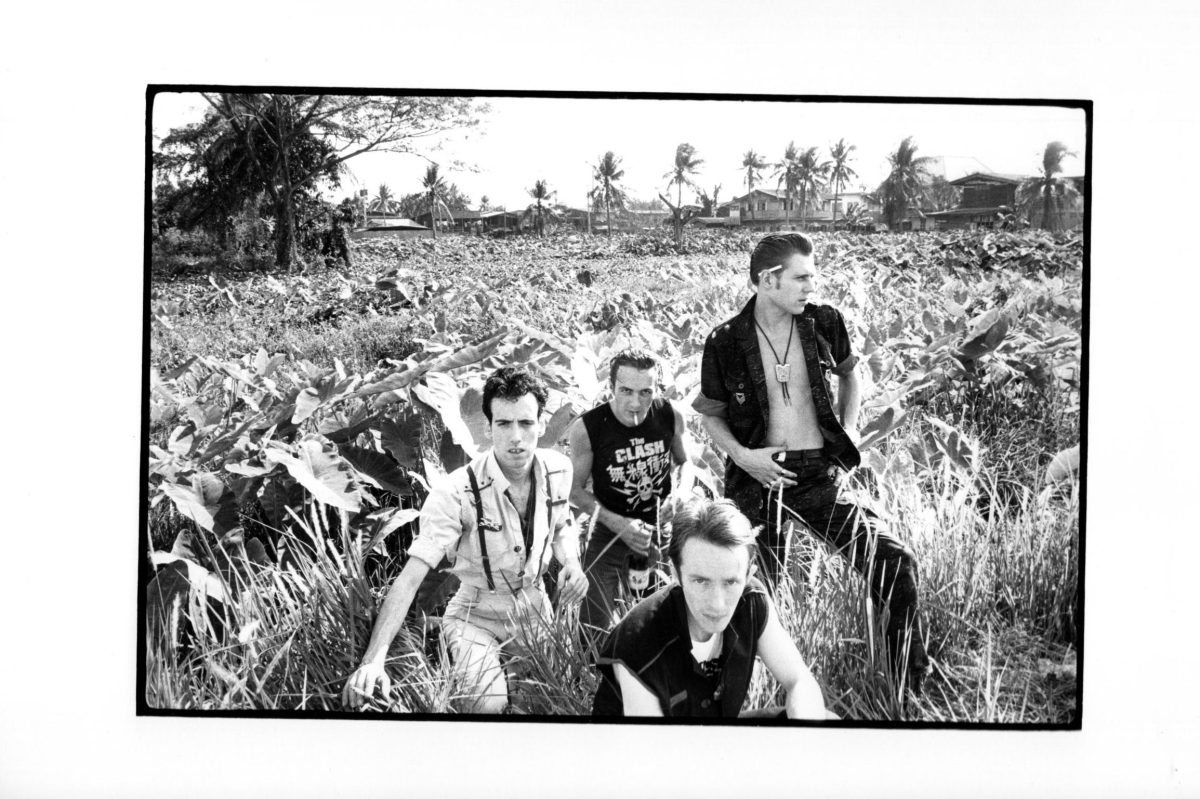

During the long Bond’s residency in New York, however, Headon had become a full-blown heroin addict. By the time of Combat Rock’s release — and after a calamitous tour of the Far East, when tensions boiled over about his spiraling drug use, not to mention the sprawling double album Mick Jones proposed provisionally titled Rat Patrol at Fort Bragg — he’d been fired.

“They left me in New York working on the film of the Bond’s shows, and went off to London, and then the Far East tour,” Letts recalls. “By the time I met up with them in Texas to make the ‘Rock the Casbah’ video, they’d lost Topper, and it was fucking weird. The vibe had definitely changed. Obviously, a lot of shit had happened in that time.”

“What happens is you feel like you’re actually losing control of yourself, to the point that your feet are starting to leave the ground,” recalls Jones of the fame the band had achieved. “One needs to have one’s feet on the ground to have a sense of reality. That was starting to go.”

“That’s why it all fell apart in the way that it did,” Simonon adds. “It was a natural, organic way of something unraveling.”

The band, of course, was hardly a spent force. They deputized Terry Chimes, who’d played drums on their debut album, to fill in for Headon and headed out on a massive tour of the U.S. Facing a ragtag audience — half tentatively embracing the already spent punk chic of late-’70s London, and the rest sporting Molly Hatchet t-shirts and cowboy boots — and with the band’s current aesthetic having moved on from dapper ’50s London gangster to military-inspired garb, they hit on an answer.

“As the band were getting bigger, I started to notice these people coming, and they were dressed dreadful,” Vinyl says. “Some of them were really into it, but they just didn’t know. That was that connection with the Army Surplus. It was like, ‘This is the solution. They can all get Army Surplus. So, let’s encourage that.’ The idea being that it would be a whole experience. Getting to know the Clash would mean more than just buying a record. Because it wasn’t just music like a jukebox. Maybe it would influence your politics, your worldview, the way you dressed, the way you thought.”

“Our manager, Bernie Rhodes, asked me early on, ‘What if an audience goes to see a band and the audience are better dressed than the band? Why the hell should they listen to what the band has to say?’” Simonon recalls. “That says it in a nutshell, really. I really took that on board, even when we had no money [for clothes]. At that point, everybody was wearing flares, so, at all the secondhand stores, there were straight-legged trousers. We got those, and I splashed a bit of paint on them, very ‘do it yourself.’ When we started traveling the country, other people started customizing their clothes in their own way. To move forward about five years, at the time of Combat Rock, in every city there was an Army Surplus store, and if we’ve got camouflage jackets on, everyone can get a camouflage jacket.”

“What we wore on-stage, we wore off-stage, too,” Jones says. “It was a 24-hour thing.”

“The only downside,” Simonon adds with a chuckle, “was that, at some of the places we played, I thought we were playing on an Army base.”

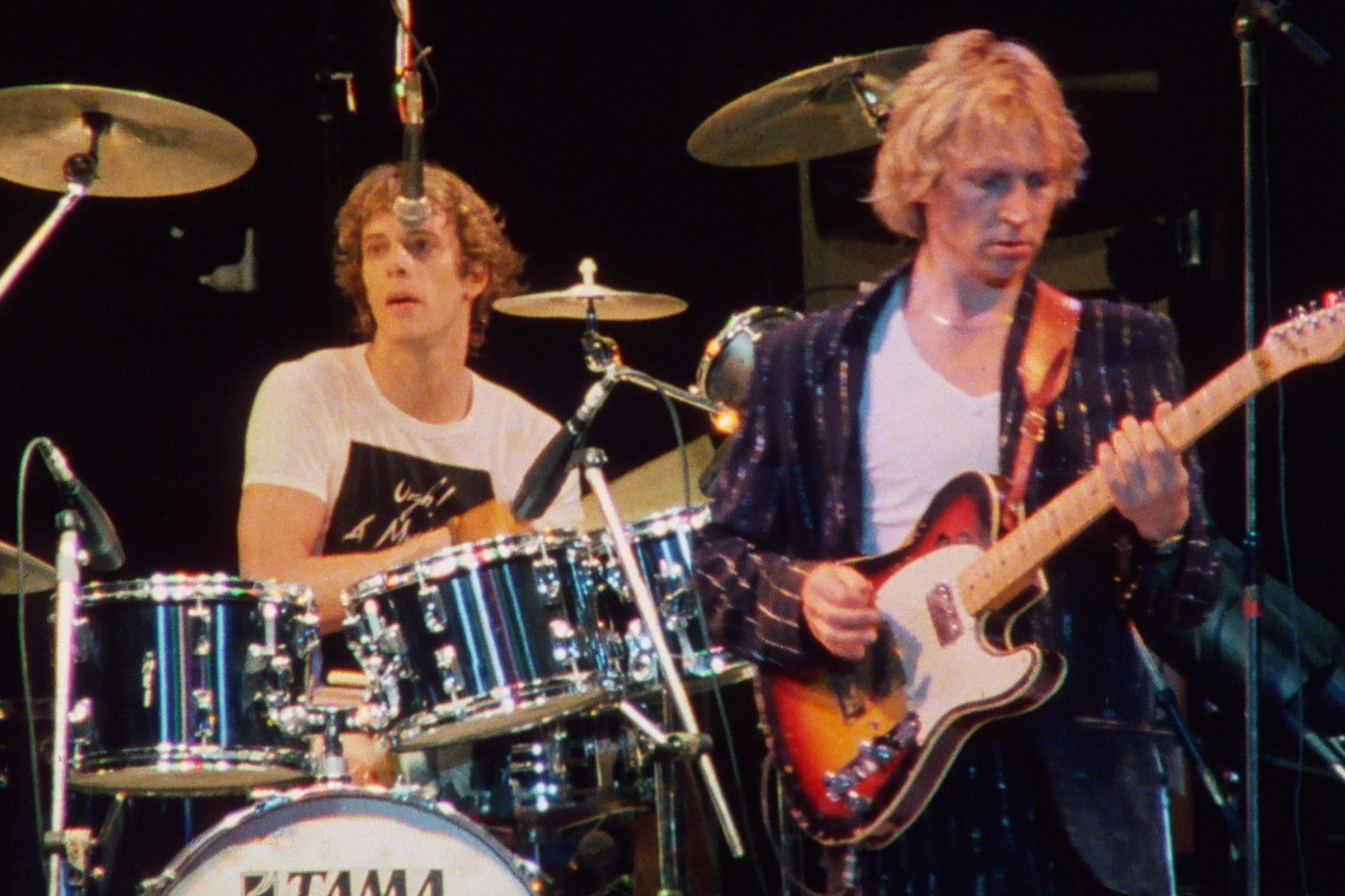

Pretty soon, with The Who about to head out on what was being billed as their final tour, The Clash were tapped as the support band.

“Townshend’s concept was that The Who was going out, so there was a bit of the baton being passed going on,” Vinyl recalls, adding that, at the time, the band’s motivation for playing massive places like New York’s Shea Stadium was pure. “It wasn’t an opportunistic thing as much as these were a lot of people to play to. I was thinking, ‘Well, there’s three quarter of a million Who fans here with nothing to do next. We’ll have some of that!’”

“Obviously, it didn’t happen that way,” Jones recalls with a laugh. “In fact, it went the other way. They went on to re-form, and we were just about finished. We didn’t deal with the forward momentum, and hence the band fell apart. Life is strange.”

Simonon, however, remains a firm believer in Townshend and his motivations.

“Pete Townshend was always on the case, right from the early days, when most people like him were going, ‘I’m too scared of punk,’ or whatever,” he says. “He came on stage with us [in 1980]. We connected to him very well. Then, before [our set at] Shea Stadium he said, ‘Come on, boys, come meet the rest of my band.’ They weren’t really very friendly. They were a bit stoney-faced. He said, ‘Oh, forget them. I’ll go back to your dressing room.’ He came back to our dressing room, and just before we went on stage, we had a game of football with Pete Townshend with a tin can.”

“The whole ship seemed like it was on the rise, but the other side of the coin was that it was fucking falling apart,” says Letts, who filmed the videos for “Should I Stay Or Should I Go” and, ironically, “Career Opportunities,” at the Shea concerts.

“There was a sense of be careful what you wish for,” Jones adds.

Still, he says, even with tensions riding high within the band, there was no thought to taking a break.

“We’re just instinctively very busy people,” Jones says. “There was no agenda. It was natural. ‘Well, we’ve done a record, so let’s go on tour.’ With The Clash, it was a 24-hour lifestyle. There was no time off. You lived and breathed it, on and off the stage.”

So with Combat Rock still riding high in the charts at the end of 1982, the band headed for one last show, at a festival in Jamaica. Soon, however, Chimes was out — replaced for the band’s headlining spot at the 1983 US Festival by Pete Howard — followed not long after that by Jones himself.

“They fired me from my own band,” Jones says, still incredulous at the thought.

“I think what’s really interesting, in hindsight, that in some ways it’s probably a good thing that the band did start to sap each other,” Simonon adds. “I don’t think we could have continued. Reality was starting to leave us, because of the success and the environment that we were in, with this collection of people that suddenly were there to carry our bags and wash our socks.”

“I loved working with them,” Letts says, no matter how intense things got within the confines of the band. “It wasn’t about ego and makeup. It was about using music as a tool for communication. Social change. I mean, we were naïve. We believed in that stuff. We still do. Because that’s what we grew up on.”

Ultimately, however, The Clash were a spent force after Jones was forced out. Strummer and Simonon carried on — egged on by Rhodes, who is virtually single-handedly responsible for the aptly titled final bow by The Clash, Cut the Crap — filling arenas around the world in 1984 and ’85, eventually embarking on one last tour, busking in remote towns across Britain, before finally calling it a day.

“The thing about the Clash is, here we are, 40 years later, talking about a band that still captures the youth of today,” Letts says. “And I think that’s down to their fundamental ingredients: They looked great, they made tunes you could dance to, films you could think about, and they oozed attitude. And you know, they could do it better than anyone else. That’s still the fundamental elements speaking to young people, and that will never change.”

For his part — with the benefit of hindsight, perhaps — Jones is proud, and more than a bit circumspect, about what The Clash achieved, particularly at its popular apex with Combat Rock.

“I always think of making records like being a lion tamer,” he says with a smile. “You go in the studio, lock the door behind you, get in the chair, and you wait to see what you can control. And I always think, ‘We’ll see what happens in 20 years.’ I always wait and see if whatever I’m doing is going to last, even [the] new bands [I work with]. When you ask me, I say, ‘I’ll let you know in 20 years or so.’”

Forty years later, with a newly spiffed up version of Combat Rock ready and waiting for yet another generation of fans to discover The Clash, it seems Jones’ answer is clear.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.