You blow a trumpet. You stomp your feet, you whack a drum. You strum a guitar. You shout Hallelujah. You sing a song. A crowd gathers. Maybe a tribe. Sometimes a whole army.

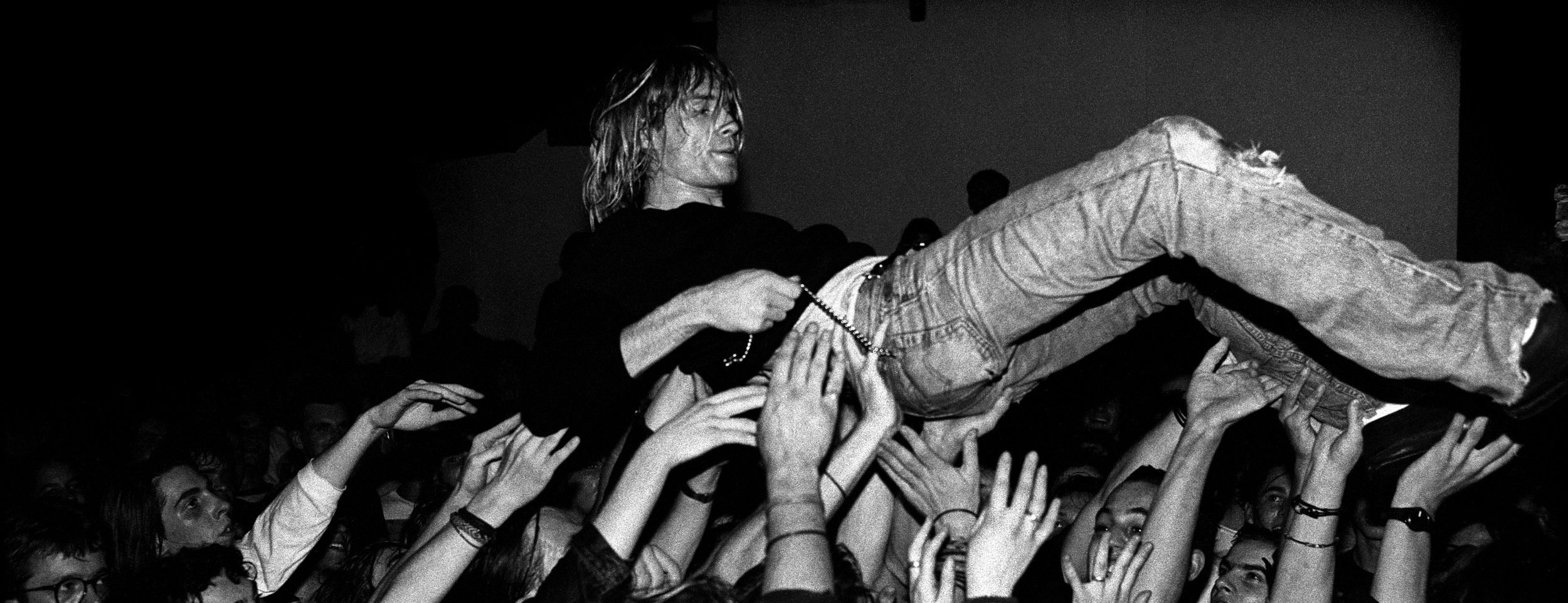

But what if an entire generation heard the call of your song?

What if an entire generation was waiting for you to sing a message, but didn’t know that until they heard you? What if an entire era ultimately came to be identified just by an image of your face?

That face belongs to Kurt Cobain, who died 25 years ago this week.

Cobain with Danny Goldberg at the 1993 MTV Video Music Awards. (Jeff Kravitz/Film Magic)In his touching and fascinating new book, Serving the Servant: Remembering Kurt Cobain, Cobain’s friend, mentor, and co-manager, Danny Goldberg is taking a new look at Cobain’s “poetic unfiltered understanding of adolescent pain.”

That seems like a wonderful way to describe Cobain’s remarkable ability to both draw outsiders in and make an entire planet take notice.

“I don’t know exactly how to articulate Kurt’s lasting appeal,” notes Goldberg. “It’s certainly not just about the lyrics, though I do think he’s a much better lyricist than people give him credit for. I mean, ‘With the lights out, it’s less dangerous. Here we are now, entertain us’—that’s as good a two lines as rock’n’roll has ever produced! And quite a few of his songs have lines that good.

“But I also think it’s the sound of his voice, the overall feeling of the production, it’s the totality of what he did. Somehow it touches a place that transcends generations. When I try to think of antecedents for it, the only thing I can think of is Catcher in the Rye. And it’s not even understandable why that still appeals to people – it’s about a private school, who even cares about these people—but there’s something about the narrator’s voice that’s more intimate than other voices, and it touches a certain sense of ‘I’m not alone’ in readers, 60 years later.

“Kurt is one of those guys, too. He’s not the only one, but he’s certainly on a short list.”

In a straightforward but unabashedly personal fashion that never resorts to banal sentimentality, Serving the Servant is built around Goldberg’s memories of the short but profound time he spent in uniquely close proximity to Cobain. Goldberg, already a legend for his work with artists like Bonnie Raitt, Led Zeppelin, and Sonic Youth, began co-managing Nirvana (with his then-partner John Silva) in November of 1990. Goldberg quickly formed a close relationship with Cobain, and for the rest of his too-short life, Cobain regarded Goldberg as a combination mentor, father figure, and brother.

The book simultaneously tells a few fascinating stories: How an unlikely gang of truth-tellers from the wrong side of the tracks (economically, geographically and musically) changed the world, and finally brought true punk rock to America’s mainstream; how a middle-aged music industry legend formed an intense, familial bond with a sensitive, sweet mercurial and troubled young genius; and how Nirvana made the leviathan music industry work in their interests, and not against them.

Tim Sommer: Why now? I mean, obviously this is the 25th anniversary of Kurt’s passing, but you must have felt there was a greater reason to write about Kurt than a date on a calendar.

Danny Goldberg: I felt that the media perception of him had diverged from my memory of him, that it was overly focused on his dark side. Not that he didn’t have a dark side – just that it was overly focused on, and his brilliance and talent and sweetness and humor had become submerged. And it doesn’t have to be that way: When I think of Jimi Hendrix, I don’t think about his death, I think about those guitar solos. I just thought the whole thing had become a little out of whack, and I thought I had a different set of experiences that could compliment the existing stuff that was out there.

I can’t pretend to be objective. This is a portrait through the lens of my relationship with him. I didn’t try to research every single nook and cranny of his life, I just tried to remind myself of the things I was involved with, and then talk to people and do some research to fill in the blanks. The whole process enforced my love for him, and my respect and tremendous admiration for his talent.

TS: What surprised you during the process of writing Serving the Servant?

DG: I was reminded of his work ethic. And I was continually reminded of how brilliant he was. He was – and I continue to believe this – he was the most brilliant person I was ever up close to in rock’n’roll. But he also had this extreme discipline about his work.

TS: This is something that continually comes up in the book: Kurt’s deep involvement in all aspects of Nirvana’s career, and the fact that he had a very positive attitude towards the major label he worked with, and other aspects of the “mainstream” music business. I think that will come as a surprise to many readers, especially those who see him as some sort of icon of anti-corporate rock.

He made that very, very clear, repeatedly—and the key quotes about how he felt about that side of the business don’t come from me, but come from things he said, again and again. He was interested in his art, he was interested in his audience, and he didn’t buy into the idea that how he connected with the audience was as important as either of those two things. Obviously, the playing field had been tremendously cleared for him by the idea that Sonic Youth had come to the same conclusion the year before. It was no coincidence that Kurt went with the same record company and the same management as Sonic Youth. He saw that Sonic Youth didn’t ‘sell out’—just because they were releasing their records in a different way, that didn’t change who they were as human beings, or the way they treated other people, or they way they interacted with their musical community, or the way they regarded their art. Kurt was quite clear about the fact that when he was younger he had preconceptions about people at big companies, but when he met them as individuals, he saw that they varied – and he would treat each person as a human being, not based on who was issuing their paycheck, but based on who they were, relative to the things he cared about.

You underline (Nirvana bassist and co-founder) Krist Novoselic’s significant role in the band and in Kurt’s life.

Well, Krist had a personal relationship with Kurt that was unique. That’s no disrespect to Dave (Grohl); Dave has had, obviously, a much more successful post-Nirvana musical career because he has talents that Krist doesn’t have, and Kurt really admired Dave as a drummer, and was very glad that he was in the band. But Krist and Kurt had been through this for years together. They grew up in the same town, and Krist was like the big brother Kurt never had, but without any sibling rivalry. Y’know, I had never talked with Krist about Kurt since Kurt died. I had about 15 or 20 conversations with Krist in the ensuing decades, but it was always about politics— he is extremely interested in and involved with politics, and that’s an interest we share. But we had never talked about Kurt after he died. At first, it was just too insanely painful, and afterwards, it just never came up. One of the joys to me about doing this book was to touch that vein in Krist’s personality about just how much he loved Kurt, and how he really understood who Kurt was. They had a great bond. Kurt really trusted Krist. He trusted that this was someone who truly understood who he was as an artist and truly was there for him. He was his partner.

I don’t want to dwell on the end – the end of Kurt’s life, that is—but I wanted to touch on something you mention briefly…the idea that Kurt’s decision to take his life may have been impacted by a possible brain injury caused by his overdose in Rome, six weeks before he died.

That’s an idea Krist floated by me, and I don’t really have anything to add to it. I did feel it was something worth including in the book. Generally speaking, when people ask why he or anybody else commits suicide, I believe there is only one correct answer: I don’t know. I have no sense that any psychiatrist, or priest, or rabbi, or yogi, or philosopher knows why people kill themselves, because any reason you can give – you can say, oh, somebody had a terrible childhood, well…most people with terrible childhoods don’t kill themselves. People are unhappy, people have drug problems, but the fact is most people who are unhappy and have a drug problem don’t kill themselves. To me, the idea that those things are causes is an attempt to simplify something that is just unknowable to human beings, as far as I can figure out.

Unlike a lot of things written about Kurt, Serving the Servant is not weighted down by his death. It is a book about Kurt Cobain’s life.

That’s what I was trying to achieve. I didn’t want to ignore his death, but I didn’t want the book to revolve around it. That’s not how I actually think of him. I started from the place of, ‘Well, what do I feel when I think about him,’ and how do I illustrate that by anecdotes, by research, by his own quotes, and so on, and it turned out, thank god, to be a book about his life, not his death. Kurt was so nice to me…I don’t even know what the words are. I can tear up at almost any moment thinking about it. And that has nothing to do with his death. It has to do with just how sweet this guy would be.

This Friday, April 5, Danny Goldberg will be talking about Kurt Cobain and Serving the Servant at the Rizzoli Bookstore in New York City, 1133 Broadway, at 6PM.

I will also note that Goldberg’s 2017 book, In Search of the Lost Chord: 1967 and the Hippie Ideal is one of the best one-volume encapsulations of what made the 1960s the 1960s, and why it still matters. Seriously, friends, if you read only one book on the 1960s counter culture, In Search of the Lost Chord should be that book.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.