Alexander Walder-Smith says there are times when he has had to explain to younger people what exactly a CD is. “We have this world of music in our pockets, on our phones now, so that’s hardly surprising,” he says. “And yet somehow they always know what a jukebox is. The idea of the jukebox has been kept alive. The jukebox just has this iconic image. It’s symbolic, not just of rock ’n’ roll, but of liberation.”

Walder-Smith grew up around jukeboxes — his father, founder of the Games Room Company, maintained jukeboxes on U.S. Air Force bases in the U.K. after World War II and would go on to introduce jukeboxes to Britain’s cafes and pub chains thorough the 1960s. Yet four years ago, Walder-Smith saw both an opportunity and the need for a rescue mission.

The Chicago and latterly California-based Rock-Ola was by then the last surviving maker of classic American jukeboxes — think ornate cabinetry, chrome-plating, florescent lights, bubble tubes, record carousel and mechanical system — the likes of rivals Cincinnati’s Wurlitzer, Michigan’s AMI (Automatic Musical Instruments) and Chicago’s Seeburg long having disappeared.

“And Rock-Ola was very good at making jukeboxes and had this glorious history but had also failed to adapt to changes in the market,” Walder-Smith explains. So he bought the company, invested heavily, launched the world’s only 200-carousel 7-inch vinyl record model and is now helping to drive a revival. That’s been helped along by the resurgence of interest in vinyl records, the trend for mid-century design and, he argues, an appreciation for the jukebox’s “earthy sound, akin to live performance” and in stark contrast to the clinical and, some say, somewhat soulless audio provided by digital streaming.

“I think people in the US are very nostalgic, very patriotic, but had to have the idea of the jukebox re-suggested to them, after decades of no longer seeing them in bars and diners. The jukebox lost its place in the culture and that finished it off commercially,” explains Walker-Smith, who decided to retain all the manufacture of Rock-Ola jukeboxes entirely in the U.S. “But the jukebox is a piece of American history — I mean, it’s from ‘Rock-Ola’ that the Cleveland DJ Alan Freed coined the term ‘rock ’n’ roll.’ It’s like choosing to buy a Harley-Davidson over a Kawasaki. So who would want to buy one not made in the U.S?”

Well, maybe ask Chris Black. He’s owner of the Sound Leisure, the only other remaining manufacturer of classic jukeboxes — and he’s based in Leeds, in northern England. Like Rock-Ola, Sound Leisure has enjoyed a COVID bounce, with people investing in their homes and in home entertainment, but with bars and other hospitality venues also buying jukeboxes to tempt us back into going out. Hotels are buying them to replace pianos in their grander suites. Companies are putting them in their office reception areas to signal how cool they are. In these settings it’s the visual spectacle of the jukebox — the name comes from “jook,” an old slang word meaning “to dance wildly,” and you’d find your jukebox in a “juke joint” — that plays especially well.

“A jukebox does connect us to the past, but there’s still something mesmerizing about them. There’s a theater to the way they work and look, especially given how intangible playing music is for most of us now,” argues Black, whose big selling machine right now is a patented 20 LP-player. The U.S. is his second-biggest export market after, whisper it, China. “Nobody needs a jukebox, but it makes for a luxury lifestyle item with a ‘wow’ factor that your typical anonymous black box hi-fi can’t match,” he says. “Wherever you see a jukebox, you’ll see people gathered around it.”

And given the complexity of the manufacture, luxury is the word. A jukebox might comprise of some 2000 parts and require expertise in woodwork, metalwork, glass-making, plastic molding, silk-screening, electrical wiring, electronics, working with liquids and product design, all under one roof — which explains why such an object will cost you between $12,000 and £24,000, for a bespoke model.

Is the Vinyl Boom Actually Hurting Independent Music?

Supply chain issues are still plaguing indie labels, artists and record stores, but are huge pressings by pop stars like Adele and Taylor Swift to blame?“You have to understand how all these materials behave alongside in each other, and what effect they have on the sound too, such that when we’re asked to do something aesthetically unusual we sometimes have to explain why it won’t work acoustically,” says Black. “You want to know why hardly anyone makes proper jukeboxes anymore? Well, just give it a go.”

It’s precisely the slightly Art Deco — even rococo — styling of the period jukebox that purists tend to go for, and vinyl-playing too, of course. That’s why Rock-Ola has a ’50s-era reissue model in the pipeline. Some hunt down a vintage machine, though finding replacement parts for regular maintenance can prove a major headache.

After all, the first automatic multi-selection coin-operated phonograph, made by the John Gabel Manufacturing Co., dates back to 1906. It gave you 24 songs to choose from. The industry exploded during the 1920s and ’30s — when you could entertain yourself with such wonderfully named machines as the Autovox, Electramuse or Gabel’s Starlite, the first jukebox to feature lit columns. The first jukeboxes to widely take the name date to around 1937, but it wasn’t until the post-war era that they really began to take off, with 1946 seeing the launch of arguably the most famous jukebox design of all, Wurlitzer’s 1015 Bubbler. Seeburg’s Select-O-Matic and Wall-O-Matic — the one you see most often in the movies — would follow. Each offered a technological, competition-quashing advance — more lights, more records, more types of records.

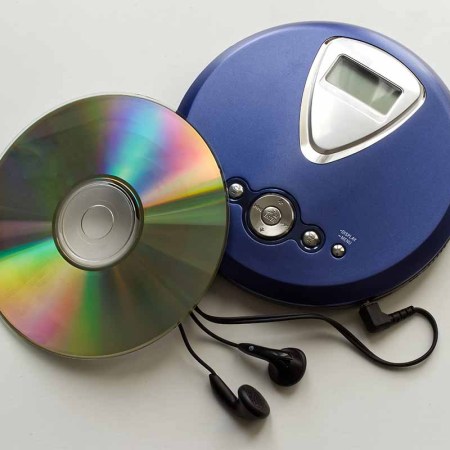

And so it is today. Inevitably, 21st-century versions might also come with the ability to play CDs, and nearly all have Bluetooth connectivity. “I have to play vinyl though mine, but my kids just shout for Alexa to play something on it,” Black winces. Environmental and safety pressures have also brought updates — matte finishing instead of chrome plating on some models, for example, the use of more energy efficient LED lighting or the replacement of the liquids used in those bubble tubes (found, some years ago, to be carcinogenic) with something sterile but just as captivating.

“Jukeboxes are essentially retro products, but that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t evolve and keep up to date with new manufacturing standards, or with the way people enjoy music,” argues Rock-Ola’s Walder-Smith. “Sure, a few years ago people would express surprise on hearing that classic jukeboxes were still being made at all. But they’re having their time again.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.