This could be the last time I see him. That’s what runs through my mind every time I decide to buy tickets for Bob Dylan and his band live in concert. It’s also technically true of any live act, not just one whose star attraction is in his ninth decade. There’s no rule stating that only musicians in their 80s and 90s will depart this earth. But for the most part, seeing musicians in their 30s, 40s, 50s and beyond, it’s easy enough to pretend that nothing will happen to them — or, with even younger acts, to you! — in the foreseeable future to keep you from seeing them again, if you’re so moved, or if you can’t make it out for this particular tour. Bob Dylan isn’t even ailing, as far as I know. He is, however, 82 years old. He tends to pass through New York City around Thanksgiving, an unspoken holiday ritual. So this November I went out to see him at Kings Theatre in Brooklyn, with my mom, who has lived through plenty of musicians leaving the party early and is of a similar mind about Dylan: each show could be the last.

Maybe I was also influenced by the online Dylanologists, who have speculated about whether Dylan’s so-called Never Ending Tour may finally defy the name he never gave it or calls it. Dylan has been keeping a robust touring schedule since 1988 (the “Never Ending” term was coined by a journalist in ’89, when he segued from one year’s group of extensive tour dates to another), but for the first time in ages, his current trek has a specific name — The Rough and Rowdy Ways World Wide Tour, after his 2020 album — along with a specific date range, albeit a wide one of 2021 through 2024. Some wondered whether this designation had additional meaning (Dylan has been inspiring this kind of speculation since well before Taylor Swift was born), further fueled by the New York Post’s claim of inside word that this would likely be his final tour.

If this is Dylan’s last worldwide voyage, he’s not going out on a greatest-hits set. He played two nights at Kings, with identical setlists; even the cover song he’s been mixing up throughout the tour was the same, with the musician settling on “That Old Black Magic” for the most recent run of dates. The 17 songs included nine from Rough and Rowdy Ways (the whole record, save the 17-minute closer “Murder Most Foul”), the one cover, five songs from a selection of ’60s and ’70s records, and a pair of one-off releases that appear on, yes, his second volume of greatest hits, though “Watching the River Flow” and “When I Paint My Masterpiece” are not exactly “the one where he tells everybody to get stoned” in terms of the popular consciousness or Forrest Gump soundtrackiness. It seems like the choice of older material is informed by the songs on his live-in-the-studio disc Shadow Kingdom, recorded during a COVID-forced touring break, but it seems just as likely those song choices were informed by what he hoped to play on tour.

Bob Dylan’s Archives Get a New Home

We caught up with Patti Smith, Taj Mahal and more at the grand opening of the Bob Dylan Center in TulsaRegardless, Dylan demonstrates more dedication to his new material than plenty of younger artists. Despite the lack of differentiation for 35 years’ worth of shows, he’s usually touring the new record, exactly the practice that legacy artists are tacitly expected to grow out of. The rock band Weezer, to pick a random example I’m familiar with, has put out three original studio albums and four EPs in the last five years alone — and you wouldn’t necessarily know it from seeing them in concert, where even the rarities skew toward their ’90s work. It must be difficult, balancing the stuff that will make the crowd erupt with nostalgic ecstasy with the stuff that reminds those same audience members that maybe it’s actually been five or 10 or 20 years since they’ve listened to a beloved band’s new song. But seeing bands I love, even those whose earliest albums I acknowledge as their best, admit that their audience doesn’t necessarily want to hear a different set than they heard last time gives me phantom arthritis.

Dylan, on the other hand, always feels new — even when, as this last time, he played almost the exact same songs I saw him do in 2021, also just before Thanksgiving. Familiarity is not a guarantee. When I first saw him in 1999, I surely didn’t know every song — and looking back on that setlist, there are still a handful I wouldn’t immediately recognize even if confronted with a pristine studio recording played directly from my own music collection. (I’m just blown away that he was playing anything from Down in the Groove.) The cliché about Dylan’s live shows is that even if you know the songs, you might not recognize them because of how he rephrases them musically, moving line breaks and transposing parts of their melodies, singing in his current voice — which is not his voice from 1999, which was not his voice from 1989, and so on back through the years. There is some truth to this. At Kings, the concert cheer that typically emerges when a plurality of the audience recognizes familiar notes of a song repeatedly arrived a minute or two into the song, when a particularly memorable line would clue people in: Oh, this is “Gotta Serve Somebody.” Even a new-ish tune like “False Prophet” growls and stomps a little harder, taking a moment to register.

The songs are not unrecognizable, however. They’re differently recognizable. Sometimes I feel like I’m going to see Bob Dylan so he can recommend his own songs to me. I never owned Greatest Hits Volume II because I had so many of the proper albums, so I didn’t often listen to “Watching the River Flow.” He played it in 2021; I listened to it constantly for two years and was thrilled to hear it again the other night. Just as often, the song will disappear by the time you next decide that no, this might be the last time and you had better go again. Some of this is just the vagaries of seeing multiple shows over multiple decades by an artist with a deep catalog and inscrutable sensibility. It’s also, however, a testament to the power of not playing the greatest-hits set, or even the comprehensive Eras Tour approach that makes sure to hit every major career milestone. Maybe at 82, that version of a setlist feels too much like a funeral. Or maybe he just really likes “Watching the River Flow.”

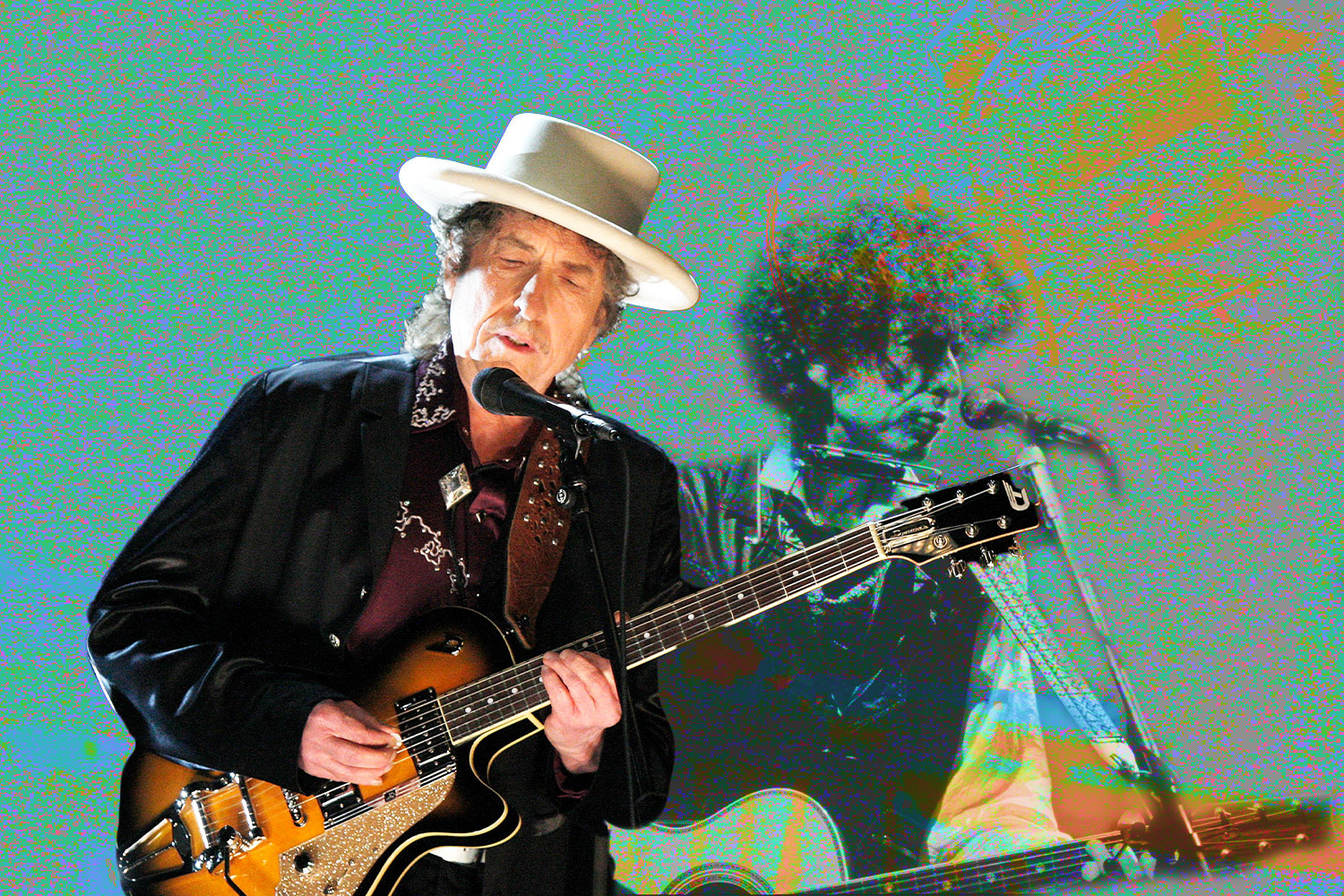

At my Brooklyn show, Dylan showed some signs of aging that have crept into his performance, primarily that he plays much of the show sitting down at his piano, though he does rise to his feet frequently and without immediately discernible reason, blurring the line between gathering showmanship and treating restless limbs. He no longer plays the guitar regularly. And yet, his onstage presence had a looseness and a comfort that never turned sloppy, keeping pace with his extremely tight and skillful five-piece backing band. He occasionally futzed with his mop of hair. During “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight,” he appeared to laugh to himself, repeatedly, during the song’s titular offer. I laughed back; I don’t know why.

Something he didn’t do was play any of my favorite Dylan songs, with the possible exception of “Watching the River Flow,” which only became a candidate after the last show. To say that this quality, of so many songs left unplayed, has a way of drawing me back to Dylan’s shows would sound cynical, like he’s keeping his audience on the hook in hopes of hearing “Tangled Up in Blue” one more time, and maybe even recognizing it from the jump. False promises, in other words. But that’s not quite it. There’s something about Dylan’s shows that feels continuous, even when he’s playing most of the same songs from the same album he was touring two years ago, and while I don’t necessarily want to see another run-through of the same set (and, frankly, may never be able to get better seats than the fifth-row tickets I stumbled into at Kings), I do want to go again. I want another song recommendation that for some reason only sticks when comes direct from the man himself. I want to see him again with my mom, who bought me the album Hard Rain on cassette in 1994, under the perfectly reasonable assumption that it included “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” (it does not). I want not to think it might be the last time, but sometimes that’s the best way to make it happen.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.