There are plenty of worse things to be labeled than “The Cute One,” so it can be a little difficult to feel sorry for Paul McCartney for being saddled with it early in his career with the Beatles. Still, it never felt right, like “cute” was almost supposed to be dismissive — John was the brains, Ringo was comic relief, George was quiet and spiritual, and Paul, well, uh, he had nice eyes. (It’s almost like judging people based on their physical characteristics instead of their talent and reducing them to a single trait is a bad thing!) But as he was getting ready to put together his second solo album, Ram, there was another Paul that had emerged in Fab Four narratives: the Controlling One, the taskmaster seen telling a visibly irritated George Harrison how to play guitar on “Two of Us” in the 1970 Let It Be documentary — the man who just one month prior to that film’s release had been accused of breaking up the Beatles in the form of a press release for his first solo LP, McCartney, without consulting the other three. (In actuality, Lennon had quietly left the group in September 1969; McCartney was just the first one with the guts to go public about the split.) For many Beatles devotees in 1970, McCartney was no longer the Cute One; he was the villain.

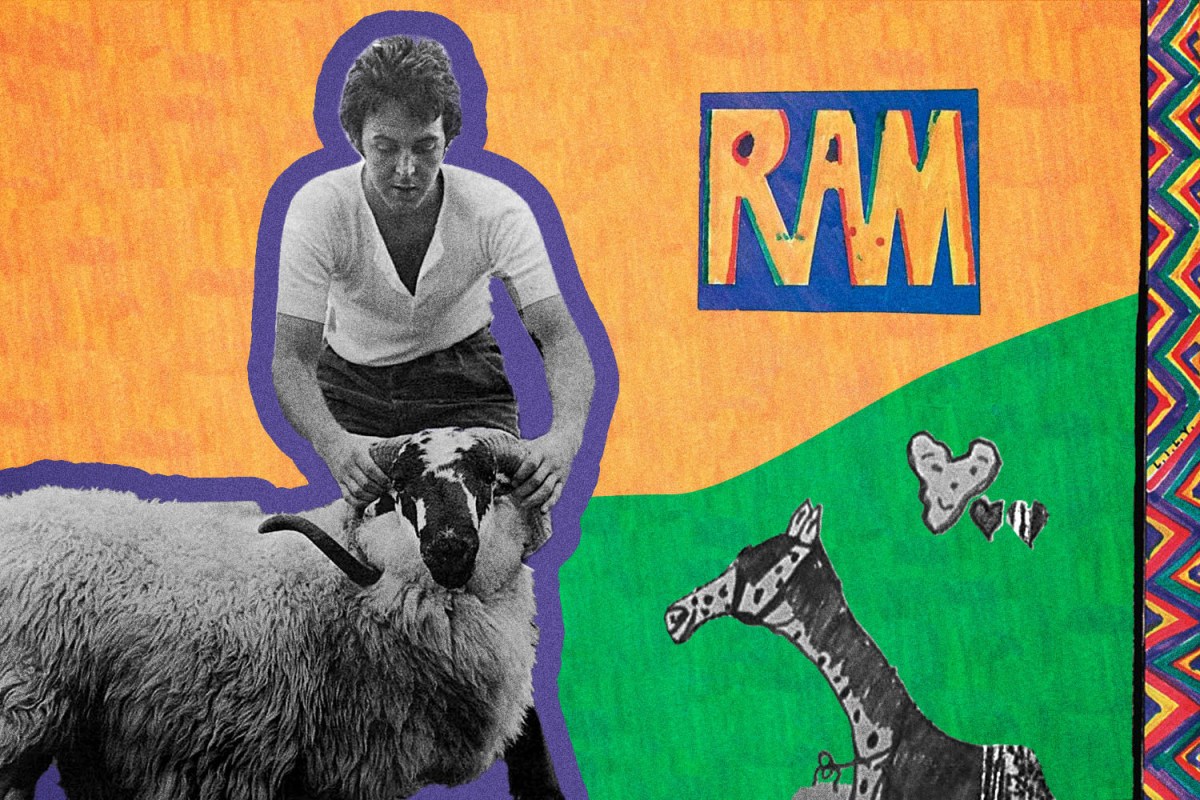

Macca’s reaction was to retreat. “I was in the middle of this horrendous Beatles breakup, and it was like being in quicksand,” he said in Ramming, a 2012 mini-documentary about Ram. “And the lightbulb went off one day when we realized that we could just run away.” The “we” he’s referring to is, of course, him and his wife Linda, who shares credit with him on Ram, contributing backing vocals and co-writing six of its 12 tracks. He and Linda spent the summer of 1970 in Scotland with their children, writing and hanging out with sheep and doing their best to avoid the media circus surrounding the Beatles’ split before decamping to New York City that fall to record what would become McCartney’s delightfully weird sophomore effort (which celebrates its 50th anniversary today).

To say it didn’t go over well is an understatement. Critics couldn’t wrap their minds around it, and Ram was universally panned, with Jon Landau famously shredding “McCartney’s cutsie-pie [sic], florid attempts at pure rock muzak” in Rolling Stone and the NME‘s Alan Smith calling it “the worst thing Paul McCartney has ever done.” (Keep in mind this was three years after “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da.”) Even his former bandmates couldn’t resist the urge to trash it. “I feel sad about Paul’s albums. I don’t think there’s one tune on the last one, Ram,” Ringo Starr told the UK’s Melody Maker at the time, adding that “I just feel he’s wasted his time” and noting that “He seems to be going strange.”

Lennon, naturally, assumed it was all about him and Yoko Ono, and while much of that was just his own ego, Ram‘s driving opening track “Too Many People” does in fact feature a few jabs at what McCartney perceived as Lennon and Ono’s self-righteousness (“Too many people preaching practices”) and Lennon’s abandonment of the Beatles (“You took your lucky break and broke it in two”). “I felt John and Yoko were telling everyone what to do,” McCartney told Mojo in 2001. “And I felt we didn’t need to be told what to do. The whole tenor of the Beatles thing had been, like, to each his own. Freedom. Suddenly it was ‘You should do this.’ It was just a bit the wagging finger, and I was pissed off with it. So that one got to be a thing about them.”

But once McCartney gets that out of his system on “Too Many People,” it’s onto the next thing, and Ram spends far less time addressing any Beatles beef than it does basking in Paul’s domestic bliss with Linda. And yet Ringo was right about one thing: it is strange. Fans and critics who were expecting the gorgeous melodies and soaring, earnest love songs like “Here, There and Everywhere” or “Maybe I’m Amazed” that had become his calling card were instead presented with something a little more left-of-center, like the layered vocals on “Dear Boy,” the complex orchestral arrangement of “The Back Seat of My Car” or the telephone, rain and bird sounds paired with goofy voices on the infinitely-odd-but-endlessly-enjoyable “Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey” medley. Some of the ’50s and ’60s influences on Ram are inescapable, like the Buddy Holly-inspired inflections on “Eat at Home” or the Beach Boys harmonies on “Smile Away,” but for the most part the record feels surprisingly ahead-of-its-time. (Yes, McCartney rocked a ukulele on “Ram On” decades before it became a twee indie-pop touchstone.)

It’s not as overtly experimental as the synth-heavy McCartney II (1980), but Ram lays the groundwork for that left turn and sets the tone for the former Beatle’s solo career by simply daring to be different. Half a century later, people have come around, and it’s now (rightly) considered to be among McCartney’s best work. But it’s understandable that at the time, fans and critics would have no idea exactly to make of it. Can you imagine expecting another “Hey Jude” and instead getting “Monkberry Moon Delight”?

The thing is, in addition to being The Cute One, Paul McCartney has always quietly been The Weird One. He’s never been afraid of a big swing, whether on schmaltzy Tin Pan Alley-influenced tracks like “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” that Lennon famously dismissed as “granny tunes,” his forays into electronica on McCartney II or experiments with multi-tracking like “Wild Honey Pie.” The result is one of the most wildly varied catalogs in music history; the highs are universally beloved works of staggering pop genius, classics that will outlive us all, while the lows are downright unlistenable — saccharine, cheesy, indulgent. Still, even his worst failures are emblematic of the fact that McCartney was never afraid to embrace his weirdest impulses and just go for it. Even at one of the lowest points in his life, when he was forced to bear the brunt of the blame for the Beatles’ breakup and tempted to simply run away from it all and disappear — something that, given the genuinely absurd amount of money he made from his time as a Beatle, would have been very easy to do — he remained a fearless songwriter, and he bounced back odder than ever. It must not have felt this way at the time after all the negative reviews, but in many ways, Ram was a righting of the ship — a recommitment from the Fab Four’s resident weirdo to doing whatever the hell he wants without getting caught up with what people think about it.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.