Conventional wisdom dictates that big-ticket franchise filmmaking has killed, or at least hobbled, the movie star as we once knew it, and to some extent that may be true. There are definitely more movie brands than ever — Marvel, Jurassic Park, James Bond, Nintendo — whose following transcends the presence of one particular star or another. The days of moviegoers following Julia Roberts, Tom Hanks, Bruce Willis or Sylvester Stallone from project to project may be over. On the other hand, some of the most enduring film series seem to stick around by sheer will of their leading actors. This summer features several manifestations of these movie-star dreams, with Tom Cruise promising the first half of a grand finish to the longest-running single-continuity film series with the latest Mission: Impossible movie, and Vin Diesel offering the same for the second-longest-running such series with the 10th Fast and Furious film, Fast X.

Mission: Impossible is indeed impossible to divorce from Cruise’s hard-charging antics, but The Fast and the Furious doesn’t immediately register as a one-man show in the same way. The first film, way back in 2001, was an uneasy-partnership thriller in the style of Point Break, with bro-cop Brian O’Conner (Paul Walker) going undercover and becoming attached to honorable thief Dominic Toretto (Vin Diesel), and it was Walker, not Diesel, who stuck around for a financially successful sequel. Neither of them appeared in the third installment — until Diesel made a post-credits appearance, heralding the return of the four “original parts” for 2009’s Fast & Furious (Michelle Rodriguez and Jordana Brewster also sat out the second and third installments).

Audiences were delighted, and the series responded by repeating the cycle as much as possible: bringing back old favorites and recruiting new value-added stars like Dwayne Johnson; subsequently benching them or killing them off; and then reintroducing or resurrecting them, preferably with flashy mic-drop cliffhangers. The outlandish car stunts remained, of course, but part of the Fast sell has long been who, exactly, the movies are pasting into the drivers’ seats (and windows, and roofs, and midair space between vehicles). Fast X draws from such a ridiculously vast pool of stars that it must cut around incessantly just to fit them all in; there are no fewer than four plotlines to follow, and those are just the good guys. (Maybe this is a stylistic tribute to the movie’s vehicles: keep four wheels spinning at all times.)

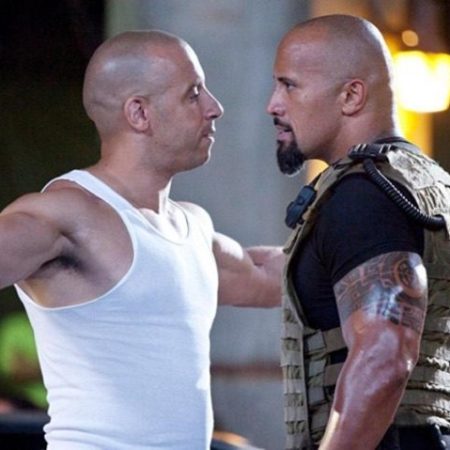

Yet despite this ensemble, the series also belongs to Diesel, especially since the untimely death of Walker during the making of Furious 7. This is apparent for any followers of the parallel behind-the-scenes soap opera, where Diesel was apparently so disagreeable that Dwayne Johnson refused to share the frame with him on The Fate of the Furious (he bailed on F9 entirely), and the series’ most frequent director Justin Lin left Fast X just days into production, hastily replaced by Louis Leterrier. (Lin retains a screenwriting credit.) The seams don’t show, at least not any more than they did on past movies that were rejiggered around various limitations. Perhaps this is because the most consistent of those limitations is Diesel himself, and his specific vision for this series.

The Car-Building Secrets From the “Fast and Furious” Are Now Publicly Available

Craig Lieberman, technical advisor for the first two movies, is sharing everything he knowsIn Fast X, that vision involves Diesel’s Dominic Toretto once again facing another burdensome challenge, with yet another bad guy (this one played with Jokerish elan by Jason Momoa) targeting Dom for this-time-it’s-personal revenge. (This was almost precisely the case in F9, although there the bad guy — Dom’s since-converted brother Jakob, played by John Cena — was more instrument than mastermind.) The rest of the sprawling “family” is in the crosshairs, but primarily because of their presumed value to Dom; some of that value is more theoretical than others, given that by now, there are major characters in these movies who have barely interacted with each other. That almost doesn’t matter; everyone, good and bad, orbits the planet of Dom.

Diesel didn’t always loom so large. In fact, this is pretty much the only context where he does. Before The Fast and the Furious, he was a magnetic character actor, racially ambiguous with a vaguely Eastwoodian squint and a kind of sci-fi growl. No wonder he seemed equally at home as a sci-fi monster-man in Pitch Black and as part of World War II platoon in Saving Private Ryan. (As film fans never tire of pointing out, he also provided the otherworldly gravel in the voice of the titular character from animated classic The Iron Giant.) Part of the original Fast and Furious allure was its pairing of this seeming realness (after all, what executive could have cooked him up?) with Paul Walker, a perfect specimen of Californian male beauty for the Abercrombie early 2000s. Diesel’s understandable sentimentality around his departed friend seems to have contributed to his tightening grip on the franchise; like Dom, he’s a purported family man who nonetheless can’t really abide anyone else’s decisions. Apart from the occasional Riddick revival, this is the only universe where those decisions have real consequence.

Diesel’s trajectory from aspiring filmmaker to unlikely movie star with a character-actor affect to de facto auteur rewriting his autobiography recalls a figure from the heyday of star power: No less than Sylvester Stallone, whose possessiveness of Rocky Balboa (granted, a character he created) and to a lesser extent John Rambo (a character he did not) has defined and at times eclipsed his broader filmography. Like Diesel, Stallone has long opted for star vehicles where smaller, more grounded parts might have provided some welcome variety, and clearly uses the Rocky series to reckon with his own career. (More proof of a sort of sensitive-alien kinship: They’re both part of James Gunn’s Guardians of the Galaxy menagerie.) Stallone’s best movies are supposed to have a strong, beating heart; in many of them, the ego beats just as strong, sometimes far louder.

Granted, the Fast movies are more generous with supporting players than a lot of Stallone pictures. In Fast X, for example, there are long Diesel-free stretches of screen time, given over to, say, Michelle Rodriguez fighting Charlize Theron, or Ludacris clowning on Tyrese Gibson — though you start to wonder if the gang has been fragmented at least in part to spare much of the cast from prolonged interactions with their ringleader. Even when the roster expands, there’s some hubris there, especially when it comes to the series’ female characters. In Fast X, Diesel share scenes with no fewer than four Oscar-winning actresses: Brie Larson, Charlize Theron, Rita Moreno and Dame Helen Mirren. Is this happening to confer upon them a certain badass-all-star status, or because Diesel truly believes that this is the caliber of performer he should be playing against?

Probably a bit of both, and if this means that Brie Larson is invited to winkingly serve looks while occasionally wielding a shotgun, maybe we’re getting the better end of the deal. The sheer enormity of the Fast X cast means that every time the movie cuts away to another bit of business, there’s another big star on display, whether it’s Momoa performing a mincing bad-guy solo, Cena doing his Kids Choice Award shtick as the fun uncle to Dom’s young son, Jason Statham throwing punches before deferring to the next movie, or Diesel himself glowering over the existential threats to his way of life. (It also means that there are several scenes that feel entirely extraneous from a story, character or entertainment standpoint, lending credence to the Diesel-started rumor that this is the first of three “final” movies, rather than two.) The series makes better use of action all-stars than Stallone’s Expendables series, and it’s still fun, mostly, even if its finest and most surprising action-movie choreography seems to be in one of the rearview mirrors that inevitably gets slammed away during a chase sequence.

In some ways, Diesel seems willing to glancingly acknowledge a degree of fallibility that Stallone spent much of the Rocky and Rambo sequels avoiding, and would only periodically embrace, usually with other writers in charge (Copland and, later, Creed, a better Balboa follow-up than anything Stallone wrote himself). Dom speaks about his hope that the next generation will surpass his (where “nobody listens,” he intones darkly, an ideological muddle of a platform if there ever as one), and his feats of strength, while patently ridiculous for a guy who’s never been Stallone-level ripped (or The Rock-level mountainous), are depicted as requiring a great summoning of protective rage. Fast X even ribs the franchise’s James Bondian carte blanche. “The real question is, why did we let this go on so long?” a shadowy agency operative asks at one point, regarding Dom and the family’s track record of globetrotting adventures (and destruction). The question resonates: Since Walker’s death lent Furious 7 some unwanted but gracefully handled closure, the Fast and Furious movies have spent a lot of time on the precipice, even for a series designed to ride that edge for fun.

Fast X does a better job of yoking Dom’s grim soap opera together with an anthology of chases and fights than F9, enough to raise confidence that Diesel might be able to steer the series into some middle-aged regret before going out in a blaze of glory. (Some kind of Old Man Toretto legacy sequel only falls short of inevitable because it would involve Diesel having the patience and restraint to walk away.) Like Stallone, he shows little sign of the pivot into character acting that might burnish his cred. Instead, he’s poised to outdo his predecessor in a bigger, weirder way. Diesel once claimed to be taking a meeting with Marvel to discuss a “merging of brands.” Unsurprisingly, this ill-defined merger between a superhero subsidiary and a human man did not come to pass. Instead, Diesel, the kind of unpredictable movie star that can’t be simply adapted from corporate IP, seems to have seen where the world was heading, and achieved what Stallone has been toying with for years: He merged with his own brand. He’s not a traditional star, maintaining a persona as he hops from project to project. He’s cruising forever. His vehicles have become one with the road.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.