There are plenty of reasons, both artistic and financial, why the Screen Actors Guild is currently on strike, just as there are plenty of similar reasons why the Writers Guild of America is also striking against the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers. Perhaps the most viscerally stirring image on the SAG side came from the union’s negotiator Duncan Crabtree-Ireland, who said at a press conference last week that the AMPTP “proposed that our background performers should be able to be scanned, get one day’s pay, and their companies should own that scan, their image, their likeness and should be able to use it for the rest of eternity on any project they want, with no consent and no compensation.”

The question of what could emerge from technology that replaces live actors with zeroes and ones — and what might be lost as a result of that, on both a financial and a moral level — is at the center of a film released long before SAG went on strike. That movie? Writer-director Andrew Niccol’s Simone, released in 2002 to tepid reviews. Watching Simone now is to watch a film uncannily ahead of its time, which anticipates some of the very issues cinephiles, labor leaders and privacy experts are hotly debating in 2023. It’s worth revisiting it to see what it can tell us about the current moment.

Niccol’s screenplay for The Truman Show, directed by Peter Weir, made for an impressive calling card for his work. As a writer/director, he is probably best known for the science fiction film Gattaca, about a near future where genetic engineering has exacerbated class differences, and Lord of War, about a politically-connected arms dealer. A sequel to the latter film, reuniting Niccol with star Nicolas Cage, was recently announced.

(Do you need a spoiler warning for a 21-year-old film? Maybe not; nonetheless, major spoilers for Simone follow.)

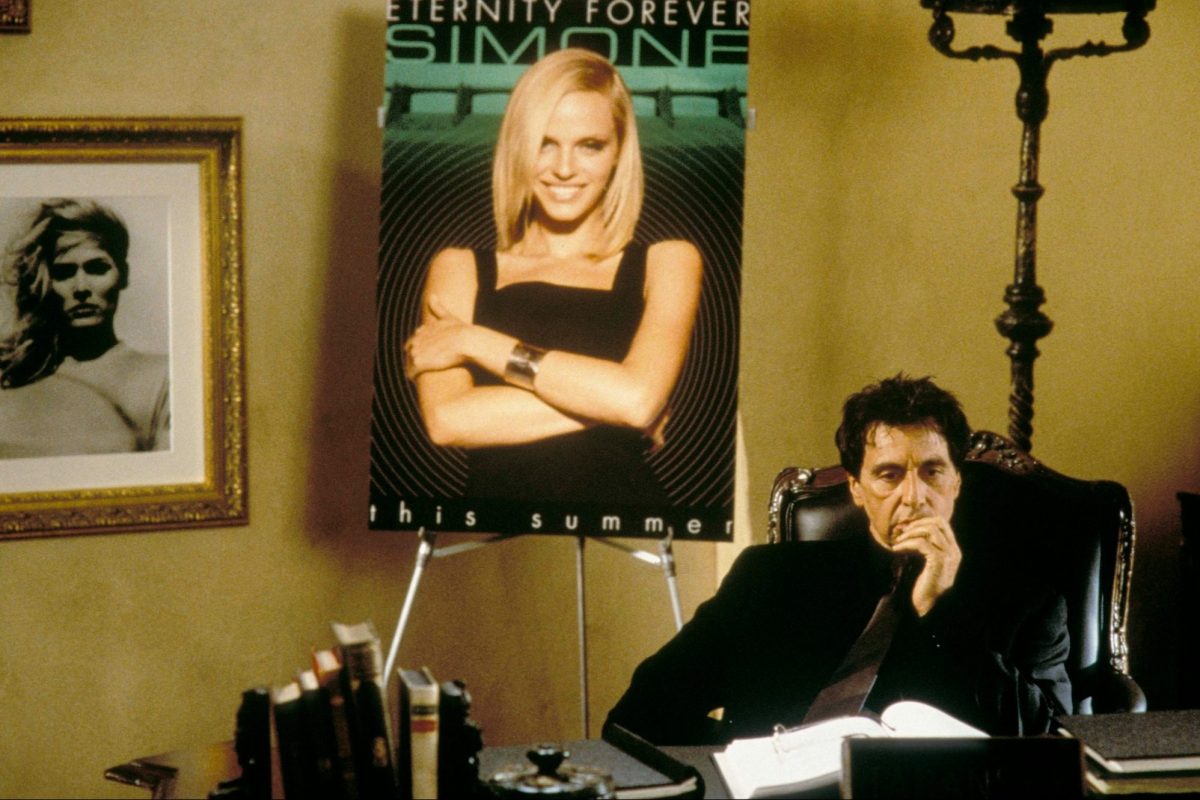

Simone begins with a director and a star at odds over the size of a trailer. That director is Viktor Taransky, played by Al Pacino; the star is Nicola Anders, played by Winona Ryder. If Viktor is the artist as neurotic intellectual — Pacino gives the character an air of desperation for much of the film — Nicola is the artist as spoiled egomaniac. She quits Viktor’s film Sunrise Sunset, and studio executive Elaine Christian (played by Catherine Keener) — who’s also Viktor’s ex-wife — shuts down production.

Enter terminally ill tech genius Hank Aleno, played by Elias Koteas, who had met Viktor years before at a conference, where he’d extolled the idea of digital actors. “You must remember my speech: ‘Who Needs Humans?’” Hank says. “Right,” says Viktor. “You were booed off the stage.” In short order, Hank dies, leaving Viktor with his life’s work: a device that can digitally create an actor, incorporating physical and artistic elements from the whole of film history. This is the Simone of the title, played by Rachel Roberts, and soon enough, Viktor has made off with the footage of Sunrise Sunset and secretly replaced Nicola with Simone. Viktor’s film becomes a huge hit, with Viktor citing Simone’s reclusive tendencies as the reason why she’s remained out of the spotlight.

In addition to its speculative elements, Simone is one part showbiz satire (think The Producers) and one part comedy of remarriage (think The Philadelphia Story). And, just as in Mel Brooks’s film, Viktor’s creation begins overwhelming him, as Simone quickly becomes a massive star, with Beatlemania-esque crowds following her around Hollywood. Viktor’s increasingly frenetic attempts to keep the nonexistence of a rising star secret — and his efforts to reconnect with Elaine — make up much of the film’s middle third. And while the comedic aspects of Simone don’t always click, the big idea at its center does.

“I wanted to send a message to the acting community, who think themselves above the work,” Viktor says early in the film — but that isn’t to say that Niccol hasn’t thought through the implications of a digital star on the business end of things. It’s more that he’s holding back on this until the right time in the narrative to deploy it.

There’s also the matter of a digital actor being inferior to the real thing — even though we see Viktor periodically augmenting Simone’s line readings and gestures with a host of qualities from various screen legends. A scene late in the film where a chastened Nicola shows up to audition for a supporting role in Viktor’s next film makes this point elegantly. Nicola speaks of having spent the time since we last saw her focusing on her craft, and the lines she delivers to Viktor make that clear. It leaves him shaken as well; there’s something fundamentally unpredictable about her work that makes him consider walking away from the (admittedly lucrative) path he’s chosen. For all her flaws, Nicola can still surprise Viktor with her performance; Simone, ultimately, cannot.

There’s something of Frankenstein in this narrative as well, and the film’s final third finds Viktor at odds with his co-creation — who has also become, for all intents and purposes, his alter ego. (There are volumes to be written about the handling of gender in this film.) This includes making Simone’s Werner Herzog-esque directorial debut, I Am Pig, and having Simone deliver a whiskey-fueled interview in which Viktor attempts to dismantle all of the goodwill his and Hank’s creation accrued thus far. It doesn’t work.

(One aside: the interview scene does feature one piece of dialogue that foreshadows 2023 in a very different way. “I think all elementary schools should have a firing range,” Simone says at one point. “How else can children learn to defend themselves?” What played as intentionally transgressive in 2002 now seems about a year away from being something a politician will endorse on the campaign trail.)

Black Mirror’s “Joan Is Awful” Is The Most Prescient TV of the Year

As AI becomes a part of daily conversation, the episode is the most frightening and relevant of the entire seasonBy the end of the film, Viktor’s attempts to unmake Simone nearly prove his undoing, until Elaine and their daughter Lainey (played by Evan Rachel Wood) put two and two together and glean what he’s been up to. And while Elaine has been more compassionate co-parent than ominous studio executive, that also takes a turn at the very end of the film. (The name of her employer, Amalgamated Film Studios, is a nice touch — especially since distributor New Line Cinema was, at the time of Simone’s release, An AOL Time Warner Company.) A line earlier in the film about “the rise in the price of a real actor” is one of several places where Niccol points to the labor issues underlying this film.

Later in the film, a tabloid journalist played by Pruitt Taylor Vince (whose double act with a young Jason Schwartzman makes for some of the film’s liveliest scenes) accuses Viktor of exploiting Simone. “You have not turned over a single solitary cent to this woman!” the journalist says, unwittingly getting at one aspect of the truth.

That’s not the most chilling moment in the film, however. That comes near the end, when Viktor almost gets what he wants — including a reunion of sorts with his ex-wife and daughter. Elaine reveals that she knows what he’s been up to. “Why stop at one character when you could have a whole cast?” she asks. The film doesn’t do much with Elaine’s declaration — but her real-life counterparts seem to be making up for it.

As Viktor says at a particularly desperate moment in the film, “I can’t put the genie back in the bottle.” From the vantage point of 2023, Simone looks an awful lot like a missive from an earlier era urging the film industry to avoid opening the bottle at all.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.