At the risk of stating the obvious, by the beginning of the 2000s, the ‘90s had ended. This is true not only chronologically but spiritually; Kurt Cobain’s 1994 death was well in the rearview, and his zeitgeist-defining dream of forgoing soul-deadening jobs to make something artistically pure seemed to have died with him. The rejection of all things institutional and mainstream reduced to the “slacker lifestyle” was in decline, and as the millennium ushered in a fresh boy-band boom to replace the brief, glorious reign of alternative rock on the radio, the old ideas started to seem, well, old. Every statement of principle required an implicit, fusty “, man” that diminished its credibility of cool. “Corporate music is just trying to brainwash you, man.” “It’s all about commercialism over integrity, man.” “Rock is dead, man.” True as these things may be, they sound hopelessly lame when written down, or worse, said out loud.

Enter Deborah Kaplan and Harry Elfont in 2001. Hot off the success of their seminal coming-of-age success Can’t Hardly Wait, the writer-director duo felt emboldened for their sophomore feature, which led them to Universal, and the promise of a boosted budget in the neighborhood of $30 million. They’d have to do what might sound like a creativity-stifling gun-for-hire intellectual property gig — update the girl group Josie and the Pussycats from the retro Archie comics for a new generation — but they also had ideas of their own. While the studio knew brand-name recognition could be used to coax audience into theaters, the Kaplan-Elfont brain trust realized it could also serve as an effective Trojan Horse for smuggling in a more pointed agenda. The previous decade’s dwindling cynicism towards pop would have one last, noble gasp at the multiplex, they decided. If they failed, and the box-office bellyflop of Josie and the Pussycats cost the production’s parent company tens of millions of dollars (which it did), all the better.

It’s not easy to find a studio-sanctioned film with such a deep, wholehearted contempt for the capitalistic mandates of art. (Maybe the Wachowski sisters’ take on Speed Racer, another expensive bomb cloaking its commentary in wormed-over IP.) The advertising sold it as a fun, sexy, teen-friendly romp, which may have had something to do with the dismal receipts falling just short of $15 million. Ebert savaged the writing in his 1.5-star review, dissing the diet-riot-grrrls leading the cast as “not dumber than the Spice Girls, but they’re as dumb as the Spice Girls, which is dumb enough.” America moved right past it, turning a blind eye to the satirical rebellion that had infiltrated cinemas.

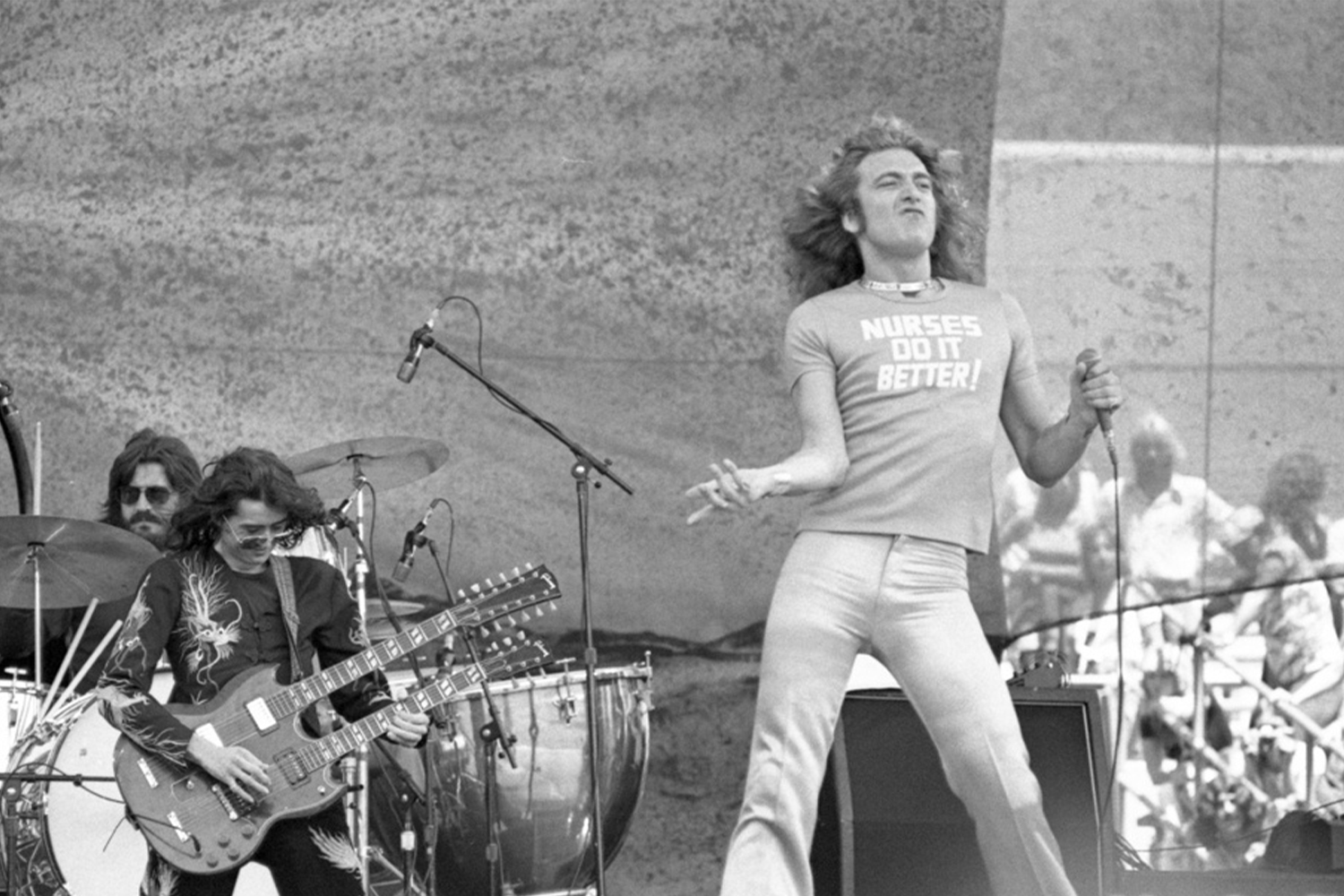

In a 2017 interview with BuzzFeed News looking back on the gradual embrace of what has become a modern cult classic, Kaplan and Elfont explained the origins of their slyly subversive take on the given material. “We were coming out of an era with Nirvana and Pearl Jam and Sonic Youth, bands that really encouraged dissent and individuality,” Kaplan said. “It was like the music industry suddenly decided we need to course-correct and feed everybody what we want them to buy and promote corporate culture and not be like, ‘Down with corporations.’ It was kind of a reaction to that. We saw it happening.” They had accepted an assignment from an entertainment conglomerate to make a movie inspired by portfolio synergy, and seized it as an opportunity to go behind enemy lines.

The script reiterates a rise-to-fame narrative well-trod for movies about pop stars, but does so with a scathing sense of critical purpose absent from similar portrayals of the biz. Gina Prince-Bythewood’s solid Beyond the Lights, for one, tracks one chanteuse’s struggle to keep it real in the face of the agents and producers trying to primp and sexualize her into someone she doesn’t recognize. Spoiler alert, but she ends up staying true to herself and recording some stripped-down singer-songwriter-type tracks. Though her decision is an age-old one — between authenticity and shiny fakery — she’s allowed to make the right choice while staying within the architecture of pop. Josie and the Pussycats makes the far bleaker suggestion that the major-label system is rotten to the core, and that any dissent within it will not be tolerated. Beyond the Lights begins with our gal feinting at a suicide attempt, a frequent pop trope that Josie reframed as part of a sinister cabal’s machinations; when anyone steps out of line, such as the Backstreet Boy knockoffs of the cheekily-named DuJour, they’re disposed of with one of the covertly staged plane crashes or overdoses littering music history.

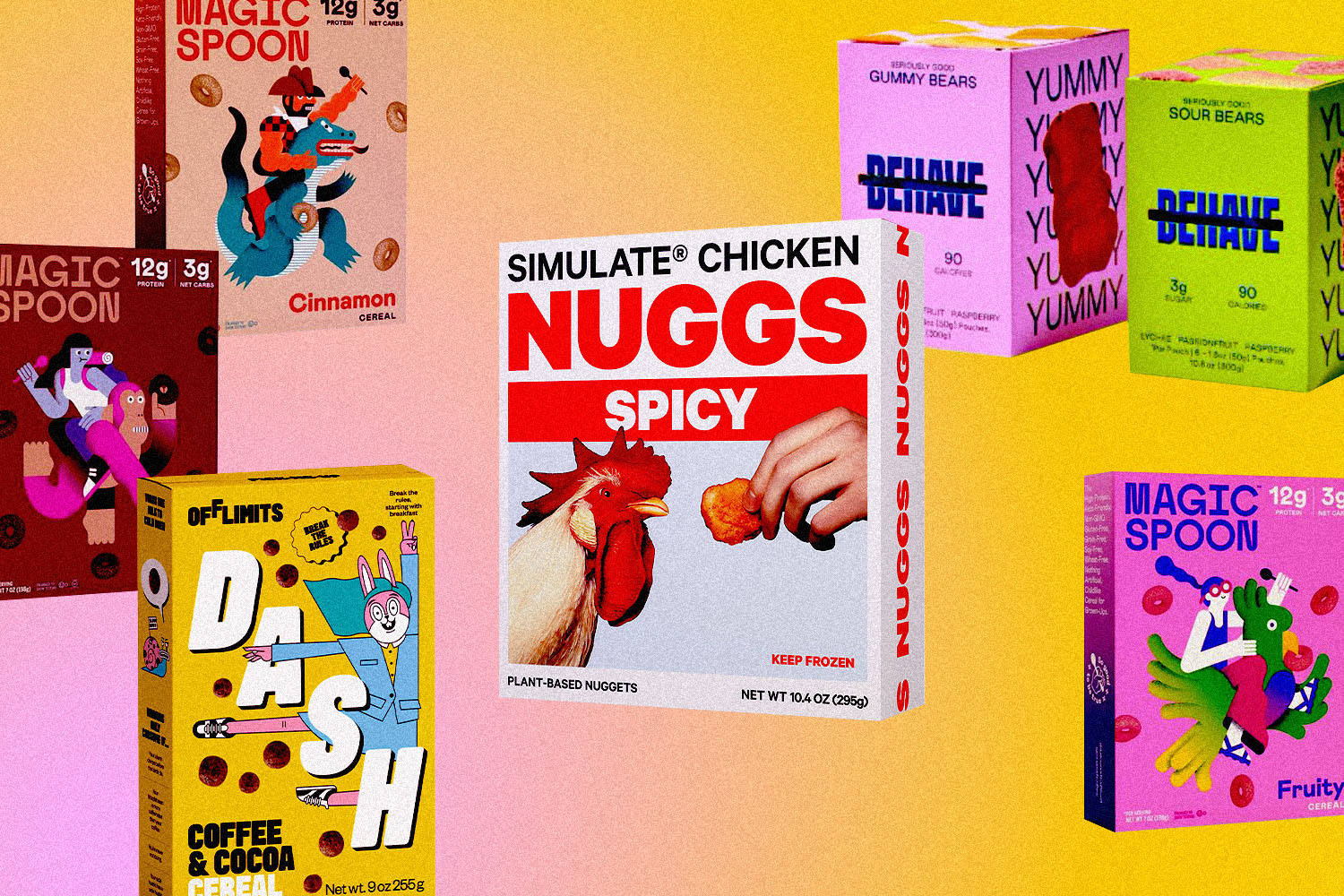

Everyone’s here to sell, sell, sell. As if in the very air, consumerism dominates the off-kilter universe imagined by Kaplan and Elfont, where the Manhattan skyline sells ad space to the golden arches of McDonald’s and Times Square is an even busier, more garish parody of itself. Product placements take up such prominent space that it turns into a joke, a precursor to 30 Rock breaking the fourth wall to ask Snapple, “Can we have our money now?” The shadowy illuminati made up of government officials, generals and other agents of The Man pumps subliminal messaging into chart-topping singles, hypnotizing the nation’s youth into buying the latest CD players or sneakers. The establishment itself is committed to churning out interchangeable product from easily controlled talent for a market they can manipulate as they see fit, a well-oiled machine into which our trio of heroines are fed.

Plucky guitarist Josie (Rachael Leigh Cook), smart-dumb drummer Melody (Tara Reid) and take-no-guff bassist Valerie (Rosario Dawson) start out as just The Pussycats, their band name changed for them by their impresarios from the nefarious MegaRecords. String-pulling executive Wyatt (Alan Cumming) and tetchy CEO Fiona (Parker Posey, in what must surely be the funniest performance of her career) force the rebrand on them, the first in a series of meddlings designed to sow dissent and tear the friends apart. They fall into the time-honored ego clash that’s broken so many rock bands before, but only because they’re forced to via mind control, yet another suggestion that the history of big-name music is nothing more than fallout from the boardroom meetings of rich squares.

Elfont and Kaplan got their on-the-DL invective past the suits by playing it off as a gag, the same detachment that makes all the difference between their hip irony and the painful corniness of movies that expound on the sanctity of rock. (School of Rock makes it work, but that’s the exception that proves the rule.) A broadside like this is best delivered with a wink, lest the denunciations of the powers that be start to sound like burnout babbling. The propaganda MegaRecords pipes into the kids’ ears urges them, “Conform! Free will is overrated! Jump on the bandwagon!” The blow is then cushioned by a one-liner about Mr. Moviefone doing all the recordings for their brainwashing project, whose chipper voice than says, “There is no such place as Area 51!” No one here runs the risk of coming off like the aging crank certain that things were better in the good old days. The film medium isn’t off limits, either, as clarified by a self-effacing split-second title card that plants “Josie and the Pussycats is the best movie ever!” and “Join the Army!” in the viewer’s subconscious.

Despite the light-to-kooky overtones of its spoofery, this is still a film that sincerely believes in the tribalism of music and what those dividing lines mean. After the members of DuJour survive Wyatt’s attempt on their lives in a plane crash, they land smack dab in a Metallica show and the metalheads summarily beat the prettyboys up. A climactic twist reveals that Fiona’s real scheme is to use MegaRecords’ tech to convince all of Earth that she’s the coolest, a sad soul having cast her lot with corporate pop due to an adolescence spent as an outcast with a speech impediment. She couldn’t be a tastemaker, so she resolved to reshape the face of culture in her image until everybody accepts a new status quo in which she has social cachet.

Because she has a compelling backstory, we feel bad for her, and the movie graciously grants her love with the equally excluded Wyatt (two words: secret albino) in the conclusion. But her pathology, of enforced influence and compulsory fandom, has only grown stronger in our present of poptimism run amok. With alternative rock dead in the ground and indie rock moldering next to it, with “selling out” an increasingly quaint concept, with stan culture accepted as right and natural for fear of retweet recompense from the legions of Taylor Swift or Beyoncé or BTS, Josie and the Pussycats hits harder than ever. The zeitgeist-tapping costumes don’t just transport us back to the out-there fashions of the aughts, but to a time of healthier opposition to the tyranny of the Top 40. As soon as Rage Against the Machine signed with Epic — owned by Sony Music Entertainment, a subsidiary of Sony Corporation of America, a division of the Sony Group Corporation — it was the beginning of the end for raging against the machine. With tongue in cheek, Kaplan and Elfont delivered a fitting eulogy.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.