Linus Sandgren is a team player. That’s why you’ve likely never heard his name even though he’s been a creative force in some of the most high-profile movies of the last decade (La La Land, American Hustle) and with some of the most high-profile directors of our time (Damien Chazelle, David O. Russell, Gus Van Sant). He’s a cinematographer, you see, and a humble one.

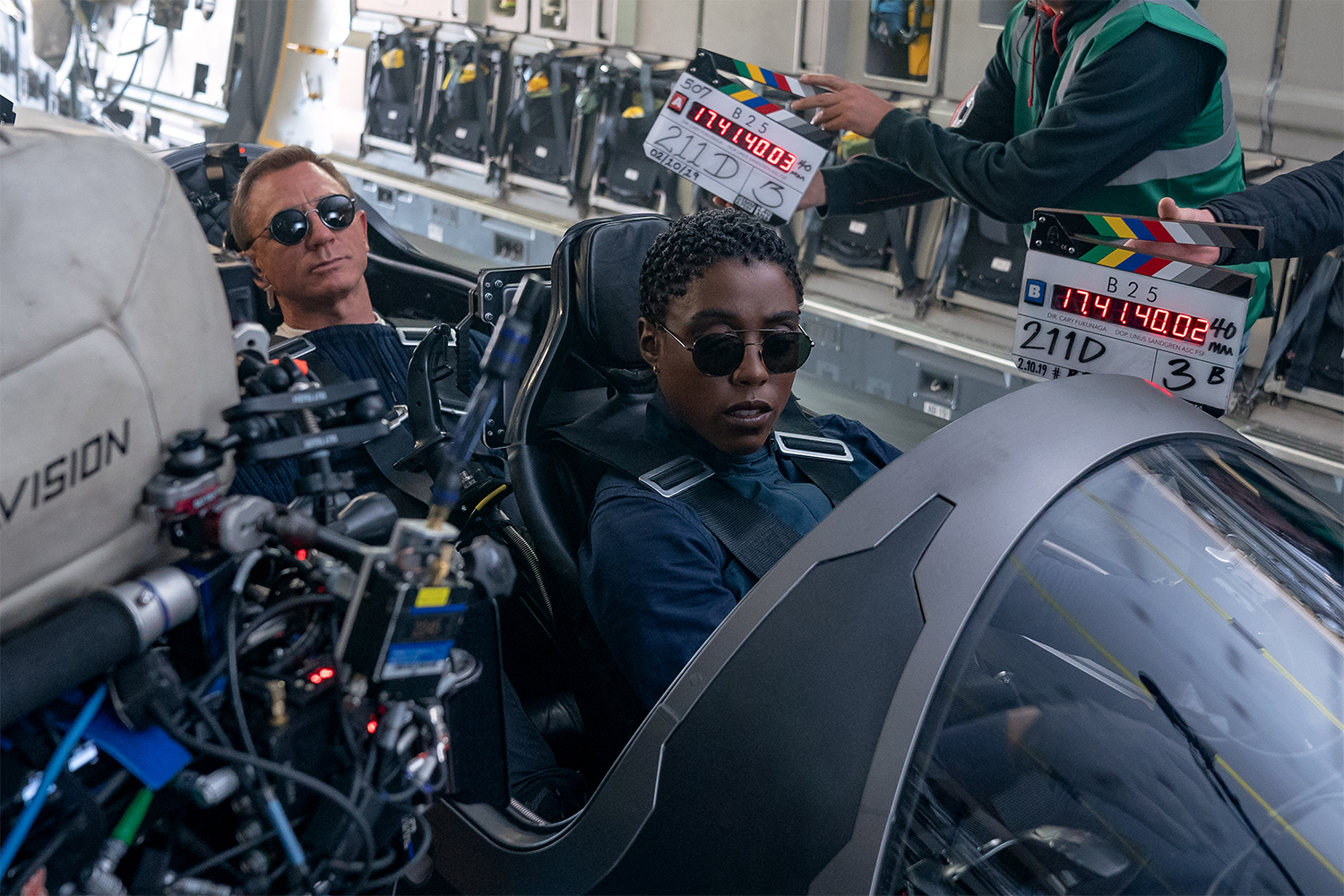

On a recent Zoom call with Sandgren about his forthcoming film No Time to Die, Daniel Craig’s last outing as James Bond but Sandgren’s first crack at the franchise, the 48-year-old first and foremost wanted to talk about his fearless leader, director Cary Joji Fukunaga.

“When I saw [the finished movie], I was so happy that Cary’s vision that he had while we were shooting the film was how he had cut it,” Sandgren tells InsideHook. “What struck me was that Cary proved to be a very confident filmmaker, executing the cut very close to the way he intended.”

On the eve of No Time to Die’s theatrical release in the U.S., it is certainly Fukunaga who is getting much of the praise for ending Craig’s tenure as 007 on a high note, according to what have been generally rave reviews, and rightly so. But Sandgren is one of the secret weapons wielded by the Bond franchise this time around — like an exploding pen or a spy watch, the impact he leaves on a project is prodigious, even if the audience can’t tell where it came from.

The first and perhaps most consequential contribution from Sandgren was the decision to shoot on film. He fought for the format along with Fukunaga, as Bond gatekeepers Barbara Broccoli and Michael G. Wilson told Variety last year, eventually shooting in both 35mm and 65mm, including the gold-standard IMAX film (a first for the franchise), which Sandgren previously used to great effect in First Man, Damien Chazelle’s Neil Armstrong biopic and moon-landing epic. While Skyfall, the first and only Bond to go all digital, is also the only Bond movie to receive a cinematography nomination at the Academy Awards, Sandgren’s analog take is already getting Oscar buzz and tugging at the heartstrings of audiences.

Even if you’re not at all precious about the film vs. digital debate, or even the theatrical vs. streaming moviegoing experience, you will viscerally feel Sandgren’s medium choices. The film stock’s warmth is the jab that sets you up for the cross that is No Time to Die’s unexpectedly touching plot, together delivering the one-two punch that is quite possibly the most emotionally complex Bond film of them all. Even Sandgren found himself getting choked up in the theater — well, as choked up as the soft-spoken Swedish cinematographer is likely to get about his own work.

“I was myself very moved by it, and it’s not easy when you are part of making the film, because you know the story, you know what’s happening,” Sandgren says. “It’s sometimes kind of hard to actually be emotionally connected and immersed in the film yourself [when you’re] part of the filmmakers. But I was. I thought it was very emotional.”

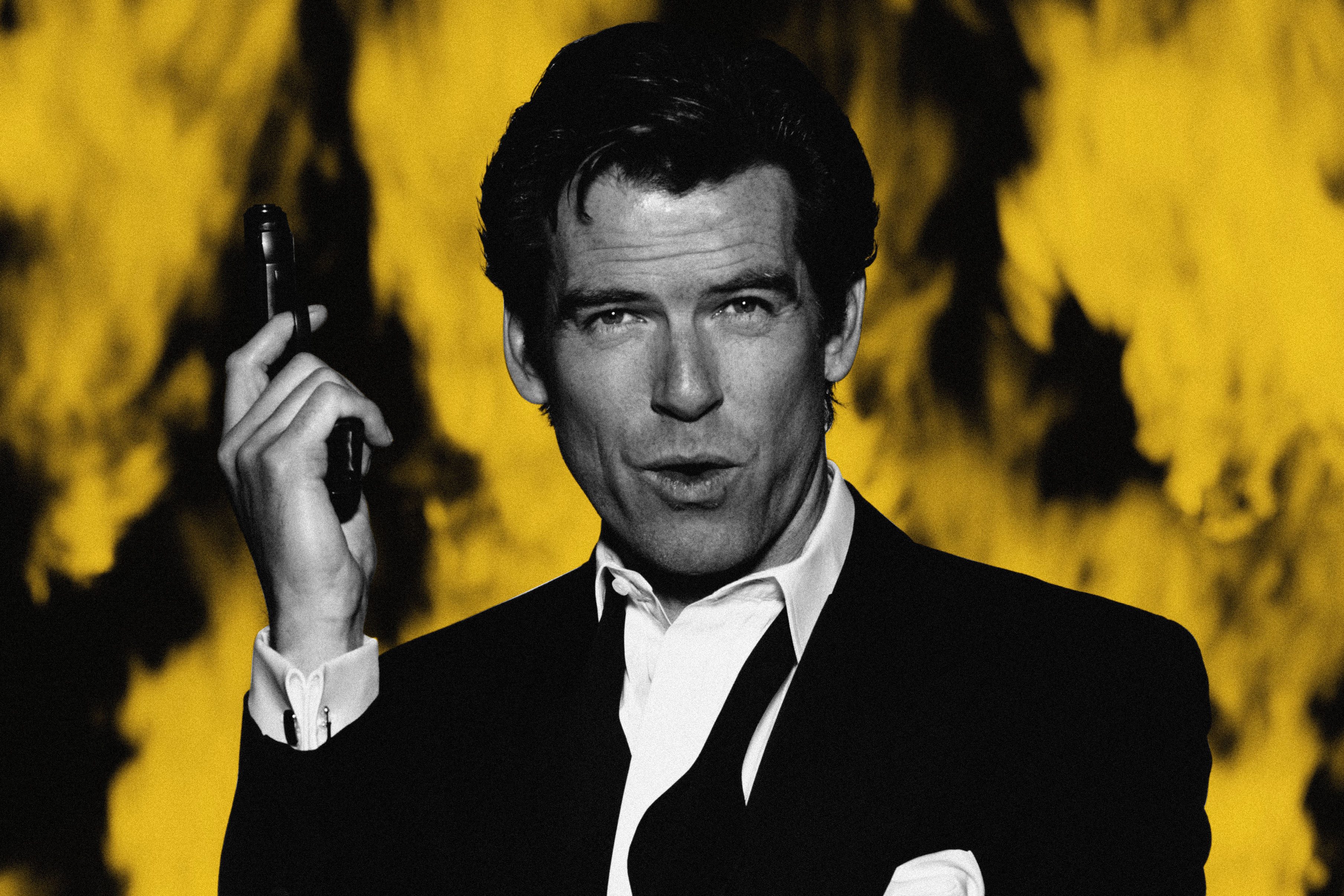

Don’t mistake that sensitive thread for a simple sign of the times. Yes, Daniel Craig’s Bond has changed, matured even, since 2006’s Casino Royale, and so too the portrayal of James Bond has been tweaked through the passing of time by the seven men who have portrayed him. But the reason you may find yourself simultaneously teary and exhausted when the credits roll after this outing have to do in large part with Sandgren’s camera handiwork.

There’s a scene near the end when Bond is in peril (that’s not a spoiler, he’s always in peril in the last 30 minutes) that may remind you of La La Land — not because Ryan Gosling or Emma Stone show up in dance shoes, but because Sandgren employs a long shot that’s as impressive as the freeway bonanza “Another Day of Sun” and the old-Hollywood duet “A Lovely Night” that helped earn him an Academy Award for that movie.

“When we did La La Land, it was very important for us to do certain sequences in single takes because you see it’s actually happening and you are in there immersed in the storytelling, and it is an unbroken sequence. It doesn’t interrupt you, the viewing of it,” says Sandgren. “And I think in that part … you talk about the handheld sequence. We follow Bond through this extreme, violent shooting. It was a way for us to let the audience experience his struggle through that … It should feel hard, and I think it feels harder in an action sequence if you’re with someone.”

In the scene in question, Bond is fighting his way up a stairway through a rain of bullets and explosives, desperately throwing himself against walls, and at least once getting tossed like a rag doll himself, all while returning fire. Instead of the sanitized stunt double-aided action sequence you’d expect from other filmmakers, we get 53-year-old Daniel Craig putting it all on the line for his finale in a carefully orchestrated warzone. In La La Land it was a carefully orchestrated dreamscape, but the principles are the same.

“You get the dust on the lens, you get completely shot at yourself. It’s like you’re being shot at yourself more, I think, when you do [long handheld shots],” says Sandgren. “That was the idea behind it, that it should feel really, really hard. It was important for that part of the scene … he’s gone through so much, and this is even harder.”

As for Sandgren’s own experience working on No Time to Die, he says it was a joy. While he had worked with a number of big-name directors, this was another level — a Bond film — which meant little in the way of monetary or shooting restrictions. From far-flung locales to helicopter shots to intricate sets, it was a big-budget dream. But, of course, you still need a meticulous eye to turn all that cash into a two-and-a-half-hour saga that leaves audiences invigorated.

It looks like more no-shots-barred opportunities are likely to follow. He’s the cinematographer for Adam McKay’s highly anticipated, star-studded end-of-the-world comedy Don’t Look Up, which is slated for a December release. After that, Damien Chazelle has him on the hook for his next film, Babylon, which will be their third collaboration. Once you find someone like Sandgren who can turn your vision into an on-screen reality, whether it’s an A-list musical or a blockbuster about a secret super-agent, you don’t let him out of your sight.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.