Towards the end of John Wick: Chapter 4, Keanu Reeves takes a fall. Befitting this entry’s supersized running time of nearly three hours, it’s not just a regular action-hero slam to the ground. Instead, Reeves, playing the once-reluctant super-assassin John Wick, tumbles down most of the 200-plus steps at the Rue Foyatier in Paris. He tumbles and spins with a balletic relentlessness until the moment begins to resemble a gag from the Andy Samberg comedy Hot Rod where the doofus hero falls down a mountainside for minutes on end.

John Wick: Chapter 4 knows this is funny; the way it lingers in the moment, allowing it to shift from sympathy to comedy and then, finally, merging the two into a kind of rueful empathy (who among us hasn’t made their way up the metaphorical staircase only to experience a spectacular fall?) is just one of many ingenious ways it uses that glorious, ridiculous running time. But the distended length of Wick’s fall also allows time for contemplation. In another time, the audience might have been expected to spend this moment laughing at Keanu Reeves, rather than with the movie. For years, his supposed weaknesses — lack of facility with accents; surfer-ish affect; lingering memories of how convincing he was as a doofus in the Bill and Ted comedies — made him an easy object of fun, and it’s easy to imagine a Keanu type taking a beating with an exaggerated “whoa” in some kind of low-hanging-fruit spoof movie. But the unexpected, extended and rousing success of the John Wick movies have made it clearer than ever: Keanu Reeves is one of the all-time great American action stars.

He’s also a damn good actor, but then, it’s not necessarily uncommon for an extremely good-looking male movie star to gain more gravitas in age, especially as easily threatened male audiences soften their initial skepticism. Brad Pitt, Leonardo DiCaprio and Channing Tatum are just some of the actors who have gone from “pretty” heartthrob to near-universally beloved screen presence as they approach middle age. The specific establishment of action stardom is typically a younger man’s game — and when it’s not, that’s often a conscious pivot, like Tom Cruise’s steely late-career brand management or Liam Neeson’s unexpected (yet in retrospect, logical) transition from mentor to direct ass-kicker.

Reeves, by contrast, was in that game as a young man; he was 27 when he starred in his first big action hit, 1991’s Point Break. That was the year of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Terminator 2 peak, with Arnold flanked by Bruce Willis (on the more serious-actor side of the action) and Steven Seagal (on the pure-programmer side). By decade’s end, all three of those stars, along with Jean-Claude Van Damme and Sylvester Stallone, were past their peak action stardom, with only Willis especially well-prepared to make a major career in drama, comedy and sci-fi in addition to the occasional Die Hard. Reeves, meanwhile, notched the sleekest and best-loved Die Hard knockoff in 1994 with Speed, and by 1999 had kicked off the biggest movies of his career with the Matrix trilogy. About a decade after that wrapped up, his unassuming grieving-hitman revenge picture John Wick became a surprise hit and spawned another franchise. How many other performers his age have notched this many action classics?

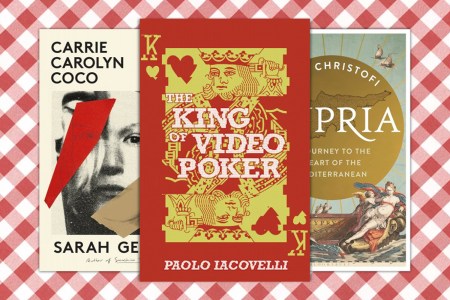

The 10 Books You Should Be Reading This July

From Keanu Reeves’s novel to an exploration of Nashville’s historyOf course, Reeves did plenty of movies in between those titles, plenty of them not action and many of them quite bad. Part of what makes him such an effective action star is that he doesn’t seem desperate for that status; he seems genuinely just as interested in making Bram Stoker’s Dracula, A Walk in the Clouds or The Replacements. His Point Break and Speed characters may be cocksure cops, but he hasn’t let youthful confidence ossify into an appeal to his draconian movie-star authority. Neo in The Matrix is baffled by the amazing world he’s sucked into, and grapples with surprise at his own outsized role in it; see not just the famous (and sometimes incorrectly mocked) “I know kung fu,” but the way that he fixes himself on one of Morpheus’s early training tasks with a little “okey-dokey” under his breath. Even John Wick, a famously deadly and unkillable assassin known throughout the underworld, is predicated on his reluctance. The first movie starts with Wick slowly emerging from his shellshocked grief at the loss of his wife, with the help of a new puppy. Bad men who come after his car and kill the dog wind up coaxing him into a more gruesome form of re-engaging with the world.

By the time Reeves reaches John Wick: Chapter 4, both the action sequences and the mythology surrounding them have gone rococo with detail, intricacy and ongoing competition with themselves. Yet the movie understand the importance of nods to the first movie’s emotional motivations, even though its events are no longer discussed directly. Wick’s rampage in the first movie led to a crime boss conscripting him into one last job in Chapter 2, and his revenge against that double-cross led to his excommunication from the assassin network in Chapter 3. Now, in Chapter 4, he wants to be left alone again, and must undertake some side missions to properly position himself to challenge the High Table, the rulers of this invisible (yet, in the fashion of staging massive gun battles at international monuments, quite visible) underworld, and the only ones who can let him finally walk away. The movie brings Wick somewhere close to full circle. He longs for the solitude he once knew, and the peace he didn’t, quite.

Accordingly, the Reeves style in Chapter 4 is arguably more minimalist than ever. He will take a pause and speak a simple, declarative sentence, or even fragment, his dialogue landing halfway between pulp-fiction profundity and a goofy koan. “You think your wife can hear you?” his old friend turned reluctant enemy Caine (Donnie Yen) asks him in a church. “No,” Wick replies. “Then why bother?” Caine presses. “Maybe I’m wrong,” Wick says. It’s the kind of thing that, as an American actor, it must be tempting to play as a parody of Clint Eastwood reticence. That in between 20-minute action marathons Reeves can imbue this line not with ironic self-awareness but genuine human feeling, reminiscent of his disarming talk-show sincerity, is something close to miraculous.

Of course, action heroics are not all about line deliveries. The John Wick series, even more than his past action pictures, have given a middle-aged Reeves opportunity to show off his physicality. In the multiple, frequently eye-popping gauntlets director Chad Stahelski choreographs in Chapter 4, Reeves doesn’t move with impossible speed or ferocity, though he’s obviously in great shape. As bullets impossibly bounce off of his impeccably tailored armor-suits, he’s graceful but methodical, hinting that Wick’s killing-machine status involves some degree of control, rather than simply unleashing hell. He’s a man consciously emulating a machine, inverting the bad guys Reeves fought in those Matrix movies. John Wick: Chapter 4 at one point brings to mind The Matrix Revolutions, not because of its orgiastic action, but because both movies contain a reminder that Reeves is one of modern cinema’s great sitters. Somehow, when he sits down with more poise and self-consciousness than a normal human, he manages to look searching while doing almost nothing.

That Reeves sometimes shows conscious effort used to be considered a point of mockery: Look, you can see this guy dimly attempting to process his surroundings! As he’s gotten older, however, that quality reads as a kind of hyper-awareness. It’s a key quality for the Wick sequels in particular, where so much of the human drama remains abstracted, as if half-remembered: Caine, for example, has a daughter (barely glimpsed) and a past friendship with Wick (never seen). And damned if Reeves and Yen don’t create something almost touching out of almost nothing, in between scenes of absolutely devastating ass-kicking.

There may yet be more John Wick movies, but the 179 minutes of Chapter 4 have the courtesy to culminate in something resembling a real resolution. Though he’s obviously not opposed to franchises, Reeves also seems to have a keen sense of endings. Even his recent legacy sequel, The Matrix Resurrections, was uncommonly thoughtful about how and why to bring back beloved characters whose stories ended decades ago. Given his age, it’s entirely possible that Reeves could soon say goodbye to the genre he has conquered. Yet his physical command of the screen is unlikely to diminish, his aura unlikely to dim, even if he heads back to more romantic dramas or offbeat indies. He’ll still be oddly compelling to watch even when he’s sitting down. Maybe every Keanu Reeves movie is an action movie, after all.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.