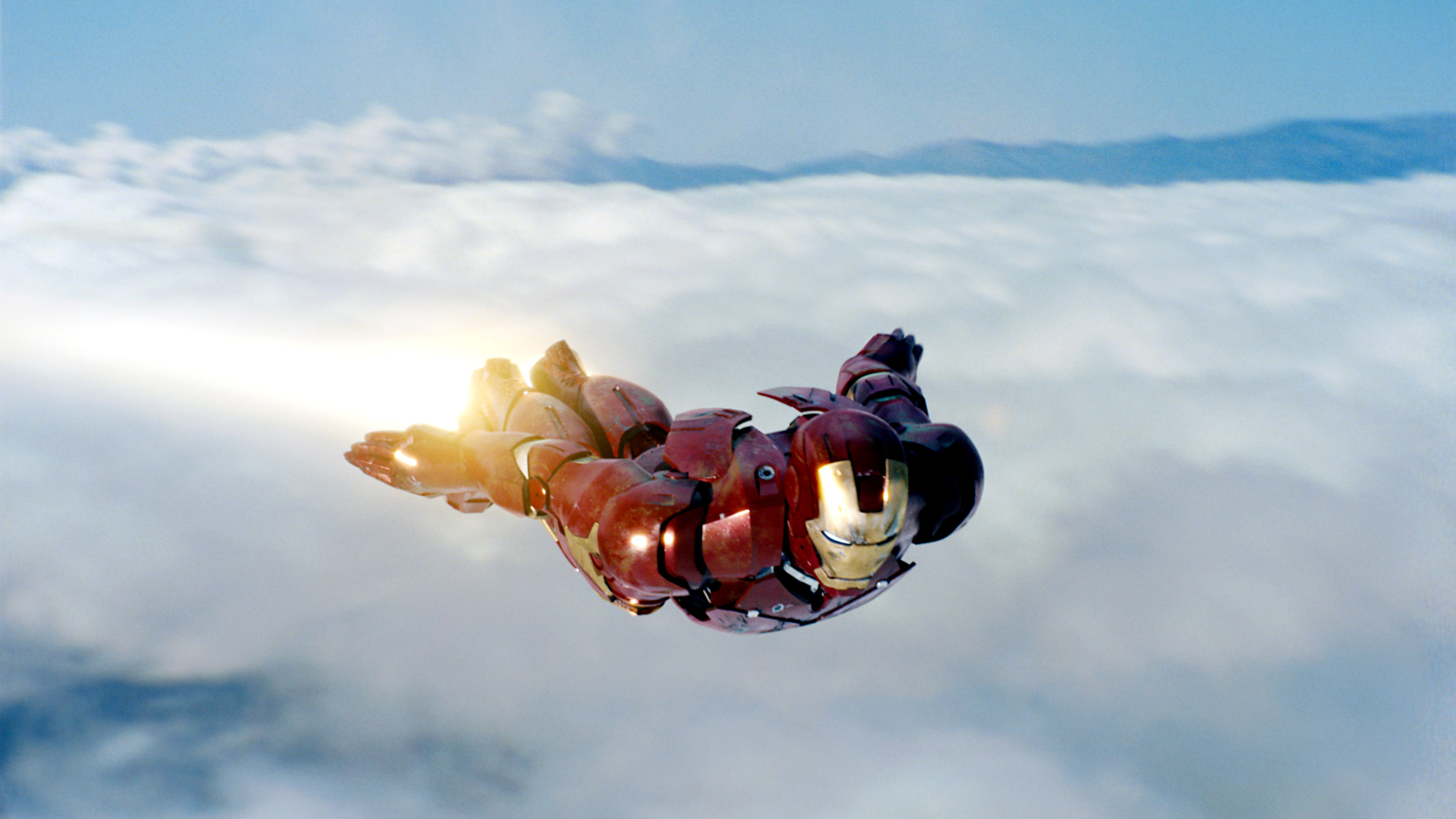

Iron Man is the gold standard.

But when the then-fledgling Marvel Studios released their first film on May 2, 2008, not even the all-seeing Norse god Heimdall could have foreseen the way the film industry would be forever altered by its release.

After all, this wasn’t one of the major super heroes: It would be Warner Bros.’s Batman who would win the box office crown that year with The Dark Knight. Iron Man wasn’t even one of Marvel’s biggest heroes, but the company had licensed Spider-Man to Sony and Wolverine and his X-Men to Fox back during its bankruptcy era in the ‘90s. So, they had to dig a little deeper into the bargain bin.

It’s easy to forget now that Robert Downey Jr. ascended back to the top of the A-list, but at the time he was cast to play Tony Stark, the troubled billionaire inside the armor, he seemed an unlikely hero. Especially since Tom Cruise had been rumored to be circling the role at one time.

As impressive as the movie Downey and director Jon Favreau made—and the $318.4 million it made at the box office exceeding the expectations of distributor Universal—it was the last minute of the film that changed cinematic history. That “button,” a sequence buried in the end credits, featured Samuel L. Jackson’s shadowy secret agent, Nick Fury, informing Stark of an “Avengers” initiative: “You’ve taken your first step into a larger world.”

He wasn’t kidding.

What started as a cocktail napkin idea from then-president of production Kevin Feige to combine the franchises of individual superheroes into this larger Marvel Cinematic Universe has resulted in 19 movies and counting: Iron Man (2008), The Incredible Hulk (2008), Iron Man 2 (2010), Thor (2011), Captain America: The First Avenger (2011), The Avengers (2012), Iron Man 3 (2013), Thor: The Dark World (2013), Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014), Guardians of the Galaxy (2014), Avengers: Age of Ultron (2015), Ant-Man (2015), Captain America: Civil War (2016), Doctor Strange (2016), Guardians of the Galaxy, Vol. 2 (2017), Spider-Man: Homecoming (2017), Thor: Ragnarok (2017), Black Panther (2018) and Avengers: Infinity War (2018).

Actors like Chris Hemsworth and Chris Evans were signed to multi-picture deals even before donning their soon-to-be-iconic Thor and Captain America costumes—because each of those characters had to fit as puzzle pieces into a larger, ongoing narrative like Russian nesting dolls. It’s the same basic model that worked for the comic books since the days when Stan Lee and Jack Kirby first combined worlds to have The Hulk punch out the rest of the Avengers. But to do so on the big screen after a decade of cinematic build-up is a staggering accomplishment that not even Lee could have imagined in the early ’60s.

And it has worked—both financially and creatively. Heading into the weekend, the 19 Marvel movies have earned more than $6 billion in North America alone, after the most recent installment, Avengers: Infinity War, debuted this past weekend with a record $250 million opening.

That doesn’t mean everything has gone according to script, however.

The studio and its parent company Disney—which bought Marvel a year after the release of Iron Man—weren’t the only ones noticing those numbers. The success of the Marvel Cinematic Universe launched a wave of aspiring imitators. None of those attempts, though, have been able to reverse engineer the Marvel formula successfully.

Warner Bros., which owns DC Comics, arguably has a stronger stable of characters with Superman, Batman and Wonder Woman. But in the haste to get their own “DCU” up and running, they rushed Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice and, later, Justice League into theaters in an effort to introduce a super-team’s worth of heroes in the vain hope that movie-goers would fall for the likes of Flash, Cyborg and Aquaman after only just a few minutes of screen-time. Didn’t happen. But the critical and box office success of Wonder Woman shows the potential for those characters if and when the studio handles them properly.

Fox has had greater success with its X-franchise. But Wolverine, Deadpool and the X-Men are all licensed from Marvel, a contractual throwback to the days before the comic company went into the movie business for itself. And the studio has had misfires: Before the 2015 Fantastic Four reboot opened, there was talk of a crossover film with the X-Men. After that movie proved to be the biggest disappointment in the modern era of the superhero genre, the plan faded away quicker than the Invisible Woman.

Paramount, having lost its connection to Marvel, had been reportedly trying to engineer a shared cinematic universe involving its Transformers and G.I. Joe franchises, but there was already too much mileage on the former and little interest in the latter. Universal tried to unearth a horror-themed shared cinematic universe, a plan that was dead and buried once the critically-reviled Mummy came and then slinked away from theaters.

All of which has made Iron Man responsible for a seismic industry shift almost as groundbreaking as the one heralded by Star Wars and Jaws. The success of those ’70s “blockbusters”—a term coined to describe the long lines of ticket-buyers that stretched outside theaters—launched a new mentality that emphasizes wide openings over platform releases, and it has dominated the multiplex ever since.

Critics complain that those bigger-is-better priorities have damned good, smaller pictures to the margins of the business, however. This Big Bang of shared cinematic universes is similarly dismissed by many cinefiles. And the cold war between studios that emerged has led them to squat on plum release dates years ahead of time for future installments of their shared cinematic universes—just to block those release slots from rivals. In some cases, this out-of-control ambition has resulted in cinematic vaporware, where movies are being announced long before there’s even a script or a director attached—which is why five films were announced to follow The Mummy long before the studio realized what a failure the Tom Cruise vehicle would be as a linchpin. (The sequels never materialized.)

Making creative decisions around financial potential could ultimately lead to a backlash from ticket-buyers if there are more and more examples of bombs like Suicide Squad than hits like Wonder Woman.

Marvel, too, has been guilty of this questionable calculus: Do you remember when an Inhumans movie was scheduled for November 2018 with great fanfare in 2014? If you don’t, you’re not alone, the studio has apparently forgotten as well, as Disney removed it from the schedule two years ago.

It’s also questionable how long this successful model can go on for the one studio that has cashed in on it. After seven to nine movie appearances each, the original core of actors Marvel has relied upon has reached the end of their cinematic lifespanin. Because their characters are tied in to the larger story, Marvel will have to eventually kill them off or recast them—and either choice is tricky to navigate when it comes to an often fickle fandom. James Bond can be recast, but it would be jarring for an audience to see someone other than Downey under Tony Stark’s goatee. (Note: the studio did successfully transition The Hulk from Ed Norton to Mark Ruffalo, but that character does not bear a lot of plot heavy-lifting.)

Marvel has done a great job of building up new heroes, like Chadwick Boseman’s Black Panther and Benedict Cumberbatch’s Doctor Strange, but can that shared cinematic universe survive for long without an Iron Man, Captain America or Thor? And because there are so many franchises seven together, how do they decide when the time is right to tear down and reboot the whole thing? One thing is for sure, eventually the Marvel Cinematic Universe will end—presumably sometime before our own sun dies out.

Ten years ago, when Iron Man first blasted onto screens, not even Tony Stark could have foreseen just how much he would change the cinematic universe and, with it, the world.

Note: RCL contributor Ethan Sacks is a freelance comics writer who works for Marvel Comics, but he is not affiliated in any way with the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.