Working the press trail for his debut feature Martha Marcy May Marlene, writer-director Sean Durkin faced repeated inquiries about whether he’d traced his depiction of an upstate New York cult from any real-world examples, and he responded to them all the same way. “No, not one specifically,” he told critic Melissa Anderson during a post-screening Q&A at the New York Film Festival. “More than basing this on something, I built it on how I felt a group like this could come to be.” His primary interest in one woman’s escape and reintegration to public life laid less in dramatizing a factual record than in the social dynamics that make any tight-knit alternative subculture possible, and their mission drift into toxicity inevitable. He lays out an intricate interpersonal architecture in the unit, lorded over by a stony patrician not above using physical force to keep everyone in line and competing for his approval. And in the lead role of Martha, Elizabeth Olsen sells the appeal of that subjugation, the perverse assurance that comes from having goals and guidelines foisted upon you.

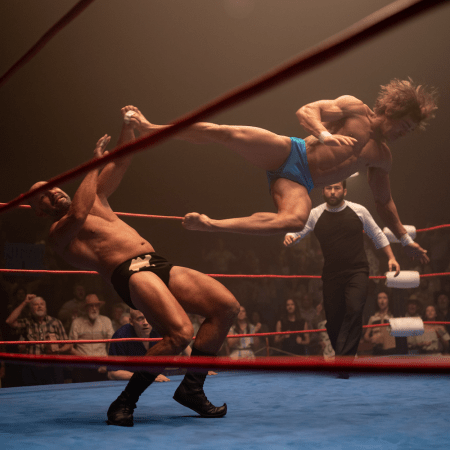

In Durkin’s latest film The Iron Claw, he doesn’t sweat the historical particulars of the wrestling Von Erich family as he nearly overstuffs his film with the major bullet points from their Wikipedia. One brother in the litter of lions has been elided completely, Chris left on the cutting room floor due to run time constraints. In recounting their overwhelmingly tragic true story, Durkin tends to hustle from one occurrence to the next, as if the film must rush to keep up with a jam-packed inventory of traumas. But even in his deep affection and esteem for his subjects, he laments the Von Erichs as an extension of the cult phenomenon, an insular cell of devout believers unable to see beyond the corrosive thoughts and behaviors they’ve been sold as a path to perfection.

“Mom tried to protect us with God,” announces the voiceover of Kevin Von Erich (Zac Efron), eldest living son following the freak death of his brother Jack at the age of six. “Dad tried to protect us with wrestling.” If sport is religion in their house, they’re a splinter sect of zealots, taking their core pieties of competition and excellence to warped extremes. Martha made it out of her psychological conditioning, her time with the unnamed group shown in flashback; whether Kevin still has the chance to “go clear” from his received masculine ideals becomes the dramatic fulcrum of a macho melodrama in which allowing yourself to be vulnerable represents the greatest victory of all. Durkin accepts the challenge as well, piercing these characters’ thickened skins with a tremulous sincerity that gently declines cruel dichotomies of strength and weakness, winning and losing.

The Best Movies, TV and Music for December

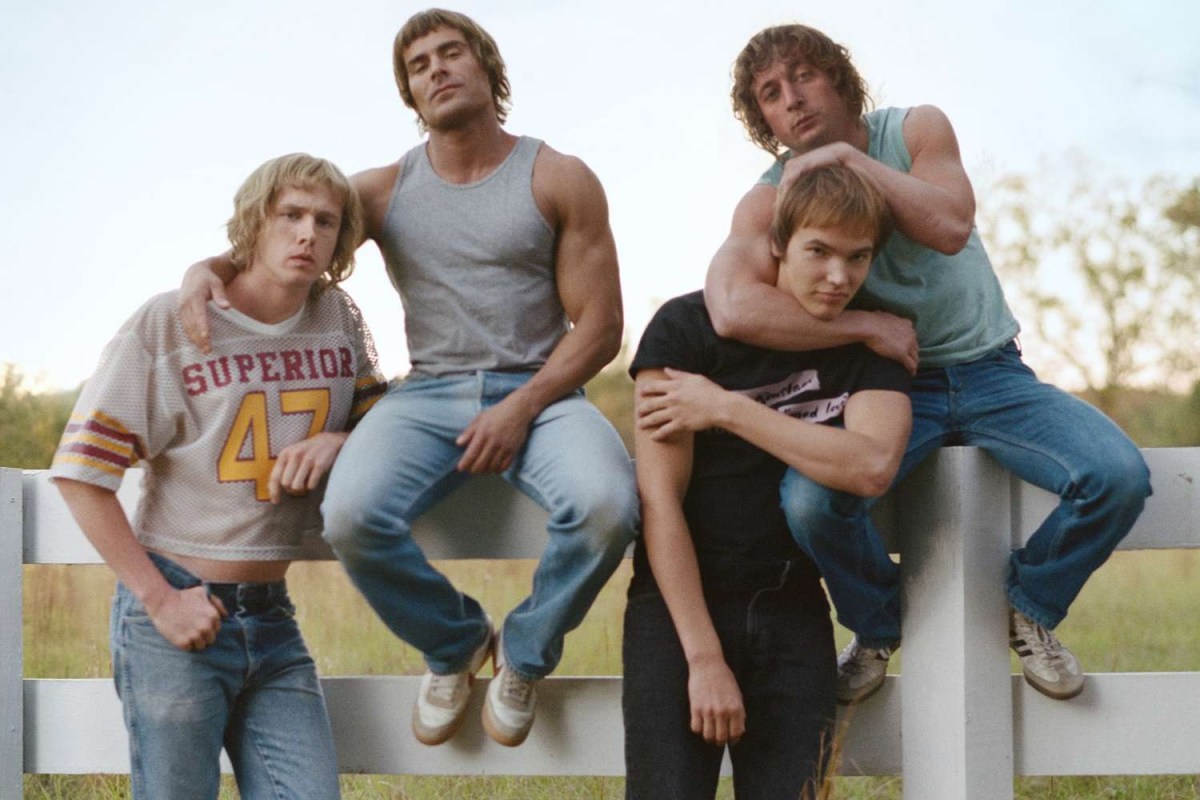

Will “The Iron Claw” be the year’s best film? Plus, the final season of “Letterkenny.”Paterfamilias Fritz (Holt McCallany) runs his house like a capricious God, handing down an official favoritism ranking of his sons from on high at the breakfast table. At the top is Kerry (Jeremy Allen White, introduced with a low-angle shot gazing up at him like a movie-star deity astride our Earth), the pride and joy for his placement on the Olympic discus-hurling team that won’t make it to Moscow due to President Carter’s boycott. Next down the line is Kevin, the beefiest slab in their bloodline, his muscles so taut and veiny and turgid with testosterone that it looks like his entire body has an erection. Then comes David (Harris Dickinson), a respectable fighter gaining ground in the standings for his natural-born showmanship that shifts the spotlight away from the meek, camera-shy Kevin. Bringing up the rear is baby Mike (newcomer Stanley Simons), who would rather noodle on his guitar than take constant pummelings, a pivot out of the family trade that Fritz permits, but refuses to respect.

We gain entry to this milieu through the surrogate of Pam (Lily James), Kevin’s girlfriend-turned-wife drawn to the sensitive soul behind his roided-out physique and awful Prince Valiant haircut. They perform rites of initiation on one another; he explains the truth behind the fakery of wrestling by which authentic entertainment value translates to advancement, and she takes this awkward man-boy’s virginity in a disarmingly wholesome car-seat hump. They sneak in their dalliance outside a rowdy rager that acquaints Pam with the Von Erichs as a way of life, where she effuses “I love your family, Kevin” with a red Solo cup in hand as she drinks the Kool-Aid. For him, his attachment to his brothers gives him a purer grounding in the destructive drive for greatness imposed on them, their fraught climb up the league ladder enabling the hooligans to party and work and be together. As in any cult, the members do as much work to maintain rank and file as the leader, bonded with each other in the knowledge that no one else can understand what they’re going through.

That hide-toughening camaraderie also affords the sons the only outlet for their feelings, the terseness that will estrange Fritz from mother Doris (Maura Tierney) falling away from Kevin once he’s among his kind. For an aw-shucks lummox — “more ribs” comes Kevin’s answer when asked what he wants from his future during a BBQ date — he’s not emotionally unintelligent, self-aware enough to admit to David that he resents getting leapfrogged by his little brother in their neck-and-neck pursuit of a Japanese tour. But this is also a private conversation, conducted in a bathroom stall while Kevin’s wedding rolls on down the hall. Like a trainer, Durkin pushes them to bare their mushier bits with his open-hearted filmmaking. His camera glides through the golden haze of Texan magic hours; major-chord guitar-hero kitsch is deployed without irony, “Tom Sawyer” and “Don’t Fear the Reaper” adroitly suited to the combination of armpit sweat and sentiment. Durkin’s boldest departure from the historical account goes all in on earnestness and pulls it off through sheer conviction, extending the most profound gesture of mercy by using the imaginative potential of cinema to reunite the wayward siblings.

Their rise-and-fall narrative drops off with brutal steepness, and murmurs of a curse grow louder as horrible twists of fate pile up around the Von Erichs. For all the demonstrative shows of love for wrestling that come from Durkin, he also identifies it as a mortally injurious force to those who practice it, and conflates the game itself with Fritz’s malignant approach to it. But that’s only in service of the prevailing emphasis on breaking the generational cycle of inherited dysfunction, a rage preached as power but ultimately holding the boys back from seeking the help they needed for their clear genetic predisposition to depression. They were taught to bear down and muscle through whatever pain might come, and the trite rejoinder that true strength lies in not in hardness but softness gains credibility through the extreme terms of the circumstances at hand.

Even when Durkin concludes on the thuddingly obvious note of Kevin’s apple-cheeked son telling Daddy that it’s okay to cry, the blunt-force pathos works for the same reason that wrestling fans have genuine reactions to staged matches: we choose to accept outsized contrivance because we believe in the feeling beneath it. For the Von Erichs, a family beset by so many misfortunes that the Hollywood treatment actually had to walk back the heaving sadness for the feel of plausibility, there was no such thing as too much — or enough.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.