Brokeback Mountain scandalized America upon its release in 2005, or at least those Americans still liable to find two men knocking boots shocking in the 21st century. Director Ang Lee raised eyebrows at the time not just for his tender, sensitive treatment of a same-sex affair, but for situating it between two cud-chewing cowboys in the milieu of the rugged West, traditionally understood to be the domain of heterosexuals. These were men’s men, terse and tough, and yet they were inexorably drawn to one another’s embrace during their camping trips in the rolling Wyoming acreage previously photographed by the likes of John Ford. Smaller minds were confounded to realize that homoeroticism could roil under the stoic surface of age-old masculine archetypes; little did these viewers realize that plenty of titles in the Essential Dude Video Collection are far gayer than they appear.

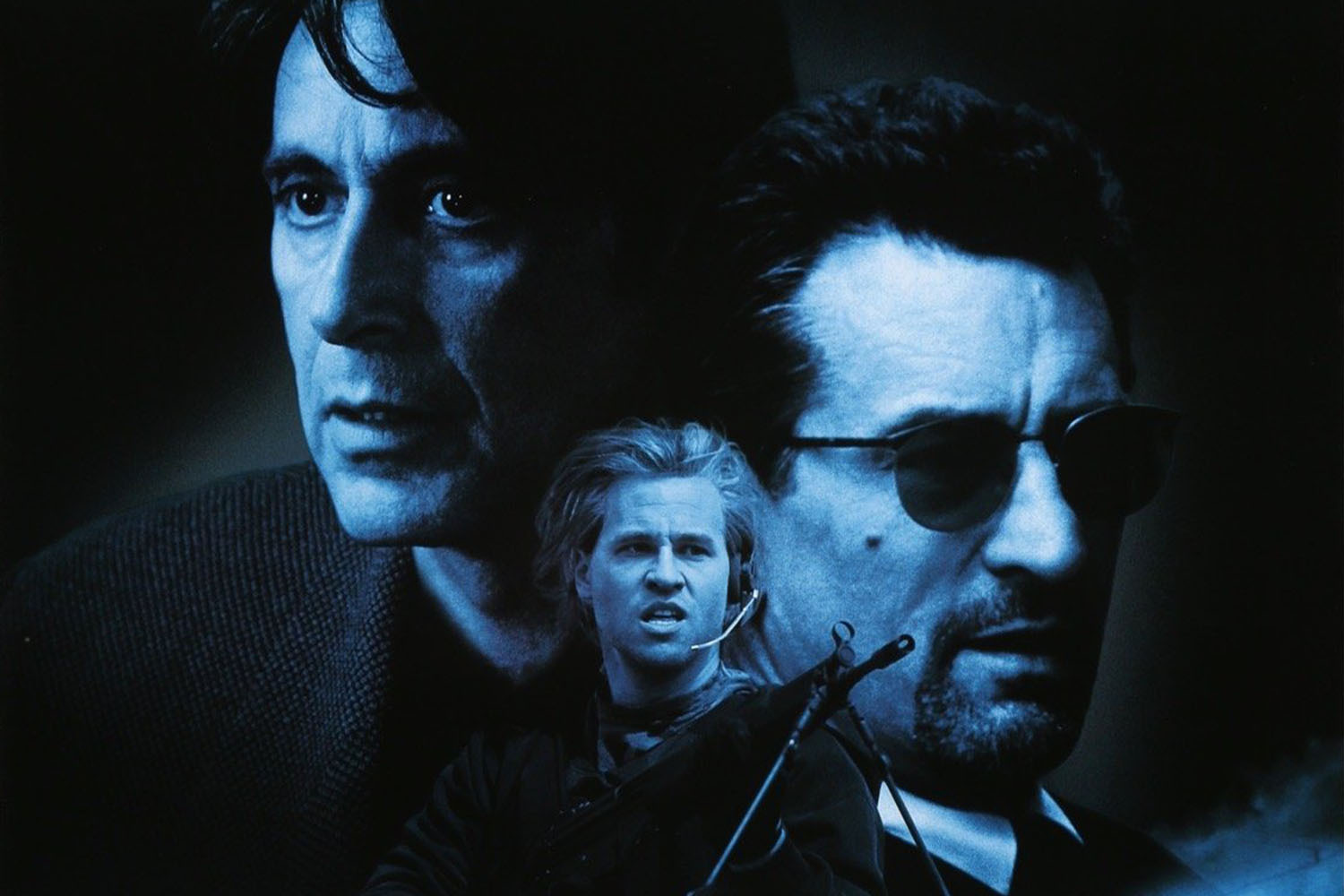

One decade before anyone uttered “I wish I knew how to quit you” and 25 years ago today, Michael Mann gave audiences a precursor of sublimated queer desire with 1995’s Heat. The seminal Los Angeles crime epic pits expert stickup artist Neil McCauley (Robert De Niro, nearing the end of his heyday) against powder-keg ultracop Lt. Vincent Hanna (Al Pacino, hitting the peak of his mad-king phase) in an elaborate, elite game of cat and mouse. As they match wits and skills, the mortal nemeses allow a begrudging mutual respect to flower beneath the enmity their jobs demand of them. But beneath that lies a magnetic pull more meaningful than mere Platonic admiration. Heat, at its smoldering core, is a delicate love story between two closed-off men unable to connect to anyone but each other. Not since Point Break had a downplayed flirtation come so titillatingly close to breaking through into the text.

Though they occupy opposite sides of the law, McCauley and Hanna both fit neatly into the mold of the classical Mann man. They’re serious, obsessive professionals, as we learn from the extensive sequences cataloguing the many steps of preparation and execution required for a heist or bust. They’re also very particular about their suits, all tailored and pressed for the height of ‘90s style, with tasteful leather gloves to match for McCauley’s crew. Though both prone to the occasional outburst of rage, these men hew toward the strong, silent type exemplified by Gary Cooper and then later fetishized by Tony Soprano. Their rough-sleek vibe makes them of a piece with Mann’s filmmaking aesthetic, too, marked as it is by hard-rawk guitar backing and cool color palettes anticipating his ‘00s turn to sterile digital formats. Mann poses his characters as warring halves of a spiritual whole, the compromised lawman and the principled thief, linked by a primal symbiosis.

In most of Mann’s oeuvre, the protagonist’s single-minded dedication to their job, whether it be robber or cop or hacker, alienates them from the people in their orbit. The case is no different in Heat, but the film introduces a wrinkle to that concept by adding multiple characters with this profile, kindred spirits forming a loose fraternity oriented around a vague notion of honor. Neither McCauley nor Hanna have much of a personal life to speak of, aside from the girlfriend the former can’t quite relate to and the wife the latter can’t stand. This line of work seems to stir up women problems for everyone wrapped up in it; McCauley’s right-hand man Chris Shiherlis (Val Kilmer) has one of the film’s many wife-arguments early on, a scene echoed in Hanna’s constant conflict with his soon-to-be-ex-wife Justine (Diane Venora) and her teen daughter (a young Natalie Portman). At every turn, they’re hassled by women for being remote and unreliable, a fairly levied charge that only brings the men bristling at it closer together.

“You’re gonna have to share me with all the bad people,” Hanna tells his wife upon returning home after a long night to an earful of guff. He explains that he can’t just walk in the door and tell her about the crimes and depravities that constitute his day like it’s what happened around the water cooler at the office. Policework estranges him from her, and as he tells her in no uncertain terms, that means it brings him closer to the scum he’s trying to clear off the streets — scum like McCauley. His most oft-quoted line restates Hanna’s same philosophy of self-imposed isolation: “Don’t ever let yourself get attached to anything that you are not willing to walk out on in 30 seconds flat if you feel the heat around the corner.”

He dispenses that pearl of gangster wisdom during the film’s most meaningful scene, one of just two proper exchanges between the men. They mostly spend the film circling one another without meeting, either observing the aftermath of the other’s handiwork with barely muted amusement or trading semiautomatic blasts from a distance. (For an added layer of meta-significance, the two actors shared billing but not screen time in The Godfather Part II, leaving audiences to wait 20 years for their true reunion.) But their paths intersect in the second act, when Hanna pulls McCauley over on the highway for a friendly cup of coffee at a diner with the reflective, shiny surfaces Mann favors. For a few minutes, they can drop the facade and extend a little civility to one another, speaking with the courtesy and deference a pro only reserves for someone they regard as a peer. The conversation concludes with both men conceding that if they have to put the other down, they “won’t like it,” but they won’t hesitate.

Directors have driven themselves halfway to insanity trying to get scene partners to display a tenth of the chemistry De Niro and Pacino radiate in this sequence. It’s an unwritten rule that the more forbidden an attraction, the hotter the furtive flirtation, and these men know full well that they can never be. They’re tentative about opening up to one another, waiting to confide in the other that they don’t feel much for the women in their lives. (It’s at this point that the Brokeback vibes are strongest, though the terse, diner-set Moonlight offers another fitting point of reference.) Because neither one wants to be more vulnerable than the other, they trade tests of how much the other is willing to reveal, from common frustrations about the work-life balance to the anxiety dreams that haunt them. It’s a moving thing, to watch someone who believes themselves to be alone discover that they have someone else there with them.

We see that behind their guarded exteriors, McCauley and Hanna conceal a yawning vacuum they’re afraid to fill, in the knowledge that doing so would make them susceptible to harm. In a few moments, a viewer can catch De Niro’s sandpaper visage cracking with the suggestion of a smile, the same expression that crept onto Pacino’s face as he surveyed one of the McCauley crime scenes a few scenes earlier. They have no choice but to stuff these feelings down, however, too dangerous to even voice aloud. The pair cultivate an unusually fatality-friendly lifestyle, but they’d hardly be the first manly-men to suppress a homosexual attraction for fear of what trouble it might bring them.

Like their cattlehand successors Jack and Ennis, Hanna and McCauley channel their energies into the occupation that allows them brief, thrilling contact. They meet again at the film’s grand finale, a shootout on foot that takes them across the tarmac at LAX, its clearings littered with disused plane parts like strategic cover on a paintball course. As they go shot for shot, both ducking for safety before they take a bullet, the space separating them gets smaller and smaller, until Hanna can land a hit and collapse it completely. Once McCauley’s down, Hanna can securely articulate his feelings without the worry that he’ll have to do anything about them. McCauley growls his final words of “told you I’m never goin’ back” as he bleeds out, Hanna offers a meek “yeah” in response, and the two men clasp hands, their words having failed them. Every time I see this film, I am devastated anew that they do not kiss, the most achingly unresolved romance since Bogie told Ingrid Bergman to get on the plane at the end of Casablanca.

There’s something inherently sexual about hardcore male competition, sweaty and grunting and fueled by a drive to win, not to mention the phallic implications of all that gunplay. The writers of the peerless sitcom 30 Rock kept this in mind when crafting Devon Banks, the Will Arnett-played rival to Alec Baldwin’s NBC executive Jack Donaghy. Their ongoing gamesmanship often tiptoes up to the line of foreplay, and because Devon is canonically gay, the writing can double-underscore the subtext. “I hate-respect you” is the honorific they bestow upon one another, the exact term for the fragile, special bond that couples McCauley with Hanna. A razor-thin line separates hate from love, one easily covering for the other, an alchemy of feelings both men lack the emotional intelligence to make sense of. The crackling tension in the air between them calls to mind another immortal Donaghy-Banks exchange, uttered after their trash talk takes on an unintended carnal edge. “I’m honestly not trying to make this sound gay,” Banks says. “No one is,” Donaghy replies. “It’s just happening.”

Heat, conversely, tragically, beautifully, trains a camera on two men who cannot bring themselves to let it just happen.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.