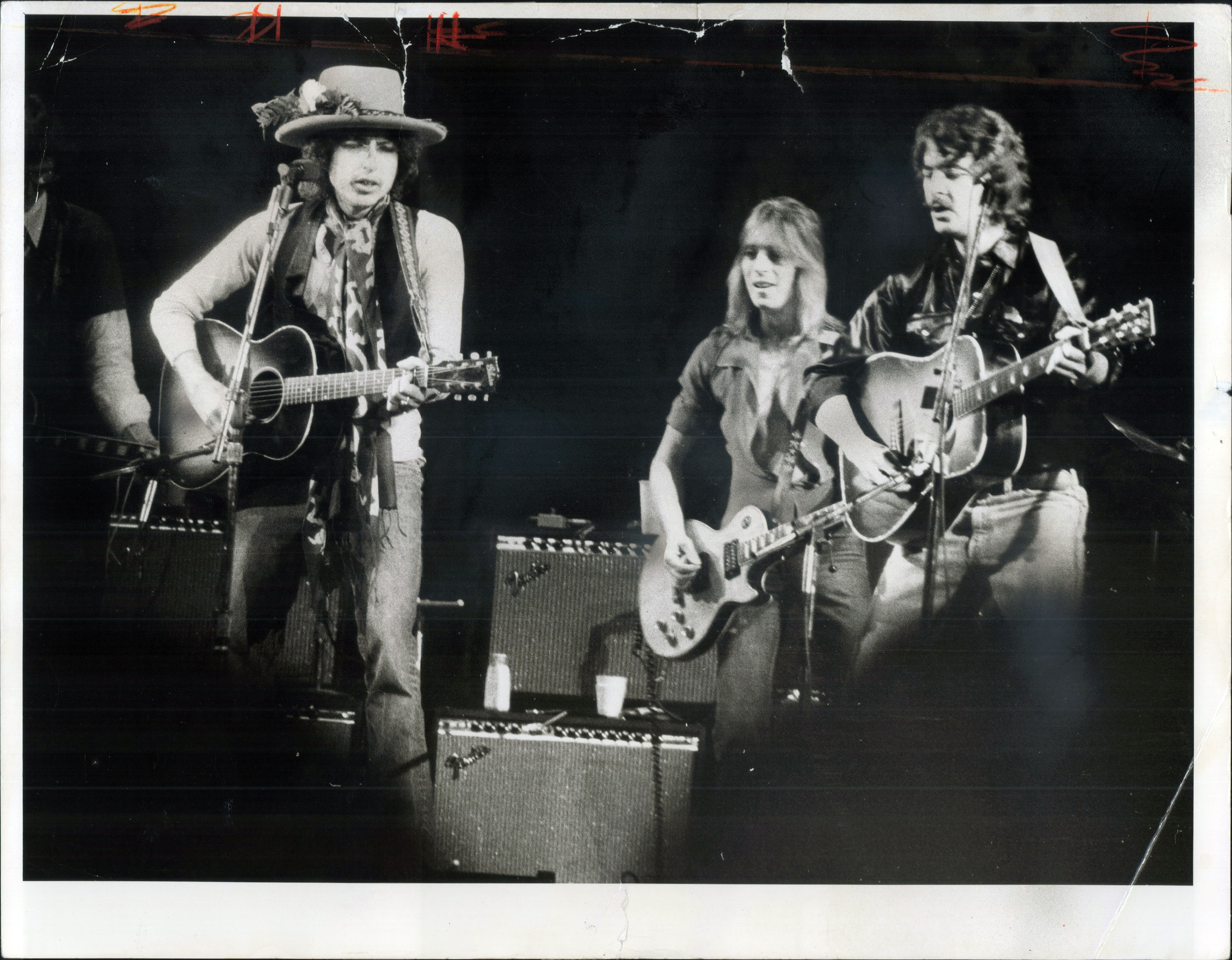

This month, Netflix shook up the unending conversation on what constitutes a documentary with the release of Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese. While “Scorsese” and “Dylan” may be the most exciting words in that title for the majority of audiences, “Story by” ended up being more fussed-over by hardcore cinephiles. Though the film purports to chronicle the folk legend’s groundbreaking 1975 concert tour, wily ol’ Marty has laced his work with creative fictions; actors appear in talking-head interviews portraying nonexistent figures, Sharon Stone takes some liberties with her personal history, and one character from a little-seen Robert Altman miniseries pops up to name-drop Jimmy Carter. Some found this approach to be nothing more than dishonest jiggery-pokery, while seasoned viewers familiar with Dylan and Scorsese’s shared fabulist tendency saw the artifice as its own slippery sort of artistry.

Aside from this particular debate, we’re currently in boom times for the concert doc in all its myriad forms. From Aretha Franklin’s church-shaking worship songs in Amazing Grace to Beyoncé Knowles-Carter’s multimedia spectacle-as-personal-portraiture-as-political-statement in Homecoming, the boundaries of the form have continued to expand in fascinating new directions. No better time, then, to codify a set of loose guidelines for effectively capturing live music on film. Below, we’ve laid out five habits of highly successful documentarians — may they be a resource to the next generation of kids videotaping their friends’ garage shows, and beyond.

Find the idea

Anyone who’s seen a concert documentary knows that it’s more complicated and complex than simply pointing the camera in the direction of the band. All of the best exemplars set themselves apart from the pack by adopting some manner of thesis statement wedged between the production numbers. Fans come to see films about their favorite acts in the hopes that they’ll gain some new insight through a closer look at people generally seen from a mezzanine away. Rolling Thunder Revue does one better, offering up a dense tangle of ideas about Bob Dylan and “Bob Dylan,” a trick of the light onto whom ‘60s and then ‘70s America projected whatever meaning we cared to summon.

In some of the most intriguing instances, however, the core idea fills a broader conceptual canvas. Though under-discussed at the time of its 2017 release, Bill and Turner Ross’ Contemporary Color posited some thrilling notions about the act of performing and what it means to those involved. The brothers embedded themselves in a showcase at the Barclays Center in which the top collegiate and high school color guard teams from around the nation twirled and danced in tandem with the musical stylings of St. Vincent, David Byrne and many others. In addition to immortalizing a once-in-a-lifetime show, the film illustrates how a unifying group activity can lend new meaning to the lives of those scrappy misfit kids on stage. This is how a music documentary’s impact extends past the end of the credits, by giving its audience something to gnaw on.

In all things, a push-pull between realism and impressionism

That being said, style counts for a whole lot in the music biz, and that goes for its film cousin as well. Each concert documentary has to strike a delicate balance between two filmmaking modes at opposite poles. On one, we have hard realism, a rigorous recreation of the event toward the most objective attainable standard. On the other, there’s a freer impressionistic technique, committed more to replicating the subjective sensation of how the show felt to a face in the crowd. The former’s logical conclusion would be a single convenience-store-CCTV feed of the venue, while the latter’s would be complete squiggly psychedelia, and so each director must individually triangulate their place in the middle.

Knowles-Carter (to whom Homecoming has been credited as “A Film by,” bringing up the same questions of authorship raised by Rolling Thunder Revue) vacillates between the two disciplines, drawing a clear distinction between the high-def musical routines plopping the camera right in the middle of Coachella, and the more intimate behind-the-scenes bits given a softer touch by Super 8 filmstrip photography. In countering one with the other, she manages to encompass the whole of the life-altering occurrence that is a Beyoncé concert, a combination of stadium-scaled pageantry and a declaration of black womanhood. That’s a more potent, rarefied version of the same magic inherent to any concert, that it can be both a communal and intensely personal experience.

There’s a big difference between character study and hagiography

I’d mentioned above that non-fiction films about musical idols give regular folks the much-coveted opportunity to get some face time with Top 40 names, and yet that proximity does not necessarily promise a revealing vantage point. So many glossy pop-docs lure diehards in with the offer of an unprecedented level of access, only to offer no analysis more penetrating than one might find in an old issue of Tiger Beat. Take the quasi-autobiographical Katy Perry vehicle Part of Me, which pays lip service to this warts-and-all principle without really committing to it. A purportedly unfiltered Perry gets real about her brief, unpleasant marriage to comedian Russell Brand, except that her big confessional moment amounts to little more than some choked-up language about overcoming obstacles and confirmation that yeah, things were pretty bad.

A subject must be willing to shed at least some measure of their vanity if they seriously intend to expose any meaningful truth about themselves, a concept anathema to the pop-industrial complex and its emphasis on cultivating a tightly controlled image. I’ve only ever heard tell of the unreleased, seldom-screened Rolling Stones doc Cocksucker Blues, but I’ll never forget a colleague’s haunting description of one passage in which the camera lingers on a groupie as she shoots up in a hotel. The Stones boldly revealed the underbelly of rock hedonism and outed themselves as its dark ministers, a startling act of self-effacement later undercut when the band sued to keep the unflattering film away from public eyes. Stardom means ego, and when allowed to influence the production, ego is the enemy of a good character study.

Don’t shoot a concert like a sporting event

The newest dirty word in the American cinema is “coverage,” a term frequently deployed by cinematographers working within the Marvel Cinematic Universe or some similarly massive franchise property. It’s a harmless term on its own, referring to the method by which a camera operator gets the shots necessary to convey a scene’s content, but it’s been slightly perverted as of late. During the blockbuster battle scenes that put cheeks in seats every summer, there’s been a certain lack of finesse that comes right down to a duller idea of coverage, specifically that all a director of photography can do once the pre-viz blows start flying is get as much of the chaos in front of the lens as possible. They’ve begun to speak like embedded war videographers or professional football telecasters, people working around events over which they have no control.

A concert may seem to be in line with this thinking — the documentarian isn’t the one running the show, after all — but knowing the setlist, scenery, and choreography ahead of time gives a documentarian an advantage. It was a great privilege to speak with the late Jonathan Demme about his Justin Timberlake picture JT + the Tennessee Kids following its premiere at the 2016 Toronto International Film Festival, a conversation revolving in no small part around the director’s process for shooting musicians. He used twenty cameras (six stationary, fourteen mobile) to ensure that he wouldn’t miss the money angle for any of Timberlake’s showmanship moments. He gets the all-important full coverage, albeit in a thoughtful and deliberate way. When JT comes running down the walkway for an exhilarating effect in “Mirrors,” the camera has been situated just so to take us along with him. It’ll come as no shock that the man responsible for Stop Making Sense, the concert movie par excellence, knows how to work his setups.

Be a servant to the talent

The thought floated above, that a subject’s ego can kill honesty in a documentary, cuts both ways. No matter how pleased a documentarian may be with their own ingenuity, no matter how critical their viewpoint, the basis for the most affecting concert movies has always been a prostrating worship of the talent. If someone has purchased a ticket to see a movie about a band or singer, it’s because they want a taste of the magnetism that compelled them to shell out $11.50 in the first place. Even a downbeat enterprise like the LCD Soundsystem film Shut Up and Play the Hits knew to counter its depiction of bandleader James Murphy as a tired former punk hurtling toward middle age with the electrifying stage presence that made him a deity to the following generation of club kids.

Under this criterion — all these criteria, really — Amazing Grace might just be the greatest concert film ever made. Sydney Pollack’s account of Aretha Franklin’s two-day recording sessions for a gospel album throws itself at the feet of her brilliance as if she were a heaven-sent vessel for the holy spirit. We get glimpses of the human Aretha in the spare moments, when she silently collects herself between songs or when she closes her eyes while her father dabs the perspiration from her forehead. The power of Pollack’s film is that it can instantly re-elevate her to that divine plane, where she reigns as the unchallenged queen of soul. The superhuman vocals, religious setting and devotional setlist may have something to do with it, but Pollack’s masterly filmmaking also plays a part in the film’s core miracle: bringing audiences by the hundreds closer to God.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.