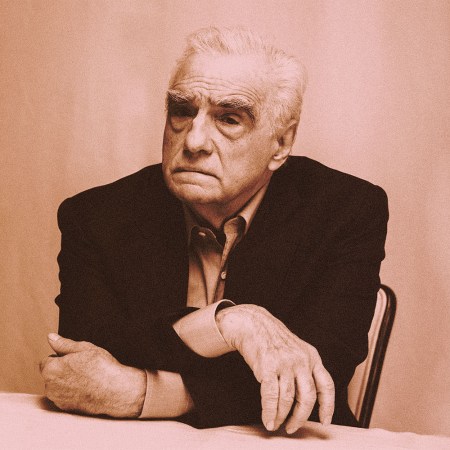

In a recent TikTok, Martin Scorsese’s Zoomer daughter and de facto social media manager Francesca quizzed her father on current internet slang: “hits different,” “slay,” “simp.” When Francesca said, by way of using one such term in a sentence, “King of Comedy was slept on,” the 80-year-old Oscar- and Palme d’Or-winning cinema legend sprang to life, immediately recalling the precise media outlet that had named one of his most daring works the worst film of the year, and the precise date, coming on 40 years ago, on which it had done so.

It was a useful reminder that, while Scorsese is the working filmmaker most synonymous with cinema itself, he’s hardly been a unanimous figure, either then or now. In fact, it’s probably because Scorsese is the cinema as we’ve known it — because of his long history of passionate advocacy for classic, forgotten and contemporary films from all over the world; because of his earnest elder-statesman’s hopes for the medium and fears for its future in a landscape dominated by corporate IP — that even today, during his remarkable late-career run of self-evidently monumental works, you can find plenty of random people on the internet, and less random people from within the Marvel-industrial complex, declaring him to be a fogey bitterly standing in the way of process, policing a narrow and exclusionary fiefdom of elitist art, made by and for people exactly like him.

This is, obviously, a stupid thing to say, and an even stupider thing to actually believe. Although Scorsese returns again and again to Catholicism, with its voluptuous mythology on the one hand and censorious admonitions against the pleasures of the flesh on the other, and to masculinity, with its frame-shaking energy, at once creative and destructive, these related concerns are personal, particular articulations within a universal project.

Scorsese’s great overarching subject is the hunger for experience, and he expresses this hunger through the full force of the cinema that has accumulated in him over four-fifths of a century of moviemaking and moviegoing. Every careering camera movement, every perspective-shattering cut, every hyperreal soundstage environment, every thrum of a soundtrack cue and every actorly invention in his movies serves to bring us closer to the great and terrible immensity of the sensual world.

Given the generosity with which he has shared his cinema with us over the years, ranking Scorsese’s films feels a bit disrespectful and inadequate — our greatest fear is that Francesca will see this list and tell her father which of his films is being “slept on” now. So, please know that almost every blurb here was written by the one of us who rates the picture in question higher than its ultimate placement. And please believe that we’ve found the experience of taking in Scorsese’s career in toto to be profoundly rewarding — as we hope you, the reader, will also find it. – MA, CB and JH

60-54. Advertisements and Branded Content: Emporio Armani (1986); “Made in Milan”(1990); American Express: “My Life, My Card” (2004), “The Members Project” (2007); Chanel: “Bleu de Chanel” (2010, 2023); Dolce & Gabbana: “Street of Dreams” (2013)

All ad-agency guys love when they get to make something “cinematic,” and Scorsese, with his grab-bag of references from the breadth of film history right at hand, is an ideal partner. His earliest publicly available commercial work is a Bertolucci-esque short, shot by Nestor Almendros, for Emporia Armani. (“Made in Milan,” a 25-minute Italian-language profile of Giorgio himself, produced by the fashionisto at the height of his Comfort of Strangers-era austere drapey powers, is… not as dynamic or thematically deep as Scorsese’s other portraits of artists at work.) Scorsese’s 2013 D&G perfume ad features Scarlett Johansson and Matthew McConaughey cosplaying as Fellini or Antonioni characters in a gentrifying NYC, and there’s a moment in his 2010 Chanel spot that I’m like 90% sure is an intentional tribute to Shohei Imamura’s 1967 experimental fiction-documentary hybrid A Man Vanishes. (Another Chanel spot is forthcoming this fall, with Timothée Chalamat replacing the late Gaspard Uliel as leading man.) “My Life. My Card” is a dizzyingly synergistic American Express spot featuring Robert De Niro and his Tribeca Film Festival, which he founded in response to 9/11 attacks, with support from lead sponsor AmEx. All the imagery in the film is tinted and smoky, as if still coated with the dust of the Twin Towers, but De Niro’s voiceover is tough and lyrical and the music is triumphant, defiant — it’s the closest Scorsese has ever gotten to New York-sploitation, if hardly as embarrassing as the first SNL cold open after 9/11, with Rudy Giuliani and Paul Simon. Scorsese also appears on-camera in his other AmEx ad, alongside other celebrities; he’s in self-parodic Marty Mode, playing into a public perception of a fussy auteur filmmaker. – MA

53. “The Audition” (Spon-con short, 2015)

Robert De Niro and Leonardo DiCaprio are two of Martin Scorsese’s highest-profile repeat collaborators, but while they co-starred in two non-Scorsese films in the 1990s, they didn’t share a Scorsese feature until this year’s Killers of the Flower Moon. Before Marty’s boys reunited on screen, their separate Scorsese runs created the general impression that DiCaprio had stepped into De Niro’s shoes, and the 2015 short film “The Audition” kids around with this idea, placing the two actors (playing themselves) in unlikely competition for the same role in Marty’s next picture. If it sounds like this premise could easily be executed in a 60-second spot, you’re picking up what “The Audition” is putting down: This was a multimillion-dollar loophole, created to get around the fact a new chain casino in Macau couldn’t receive direct advertisement in mainland China. Even within these confines — let some cinematic legends goof around whilst visiting various luxurious locations — “The Audition” isn’t exactly lovingly crafted. The casino in question had not yet finished construction, so the country-hopping ad was shot in New York, requiring only a few days’ work from its extremely well-compensated principles (a third superstar is required for the movie’s predictable albeit amusing punchline). Still, watching De Niro neg DiCaprio’s beard isn’t nothing. If it’s overlong at 15 minutes, it’s still a more concise version of Super Bowl Cinema than, say, Coming 2 America. – JH

52. “The Key to Reserva” (2007)

Commissioned, bafflingly, by Freixenet, a Spanish maker of sparkling wines, “The Key to Reserva” is Scorsese’s sole collaboration with both the great cinematographer Harris Savides and Simon Baker, star of CBS’s The Mentalist. It’s a charming, meta-cinematic short starring Scorsese as himself in one of his cuddliest, finickiest on-screen appearances (alongside Thelma Schoonmaker!), and featuring a slick suspense centerpiece pastiched from Hitchcock — count the references, beginning with the music cue from Bernard Herrmann, scoring a Scorsese film from beyond the grave, just as he did on Taxi Driver and Cape Fear. – MA

51-50. HBO Pilots: Boardwalk Empire (2010) and Vinyl (2016)

For both of these HBO series from Sopranos (and later Wolf of Wall Street) writer Terence Winter, Scorsese’s on-set presence essentially served as an extra assurance of it’s-not-TV when just HBO might have fallen short on its own. Indeed, neither series ever really lived up to the Sopranos-level expectations placed upon them, though in different ways. Vinyl was beastlier out of the gate, a noisy rock-world failure that came on so strong, complete with Scorsese co-creator credit, it almost took some time to catch up with its disappointments (HBO seemed to, too; the show was insta-renewed upon premiere, only to have the decision unceremoniously reversed once the first and only season ended). Boardwalk Empire, meanwhile, took some time to sew together what became a compelling Prohibition-era crime ensemble whose lack of a galvanizing Tony Soprano figure eventually became a distinguishing feature, rather than a limitation. This means that Scorsese didn’t direct any of the series’ best installments, even though the show as a whole paradoxically fails to match the vastness of his overall-shorter gangster filmography. It also means the somewhat statelier Winter show where he was a marquee value-add was more successful than the one he actively helped conceive (along with, perhaps fatally, Mick Jagger), making them oddly complementary in the body of his work. – JH

49. George Harrison: Living in the Material World (2011)

Scorsese picked up a pair of Emmys for his comprehensive bio-doc about The Beatles’ stealth MVP, an existential wanderer more introspective than John and more sensitive than Paul. Followed on a spiritual journey from Liverpool, through the fame machine, all the way to India, Harrison’s endless searching places him in the company of The Last Temptation of Christ’s flawed Jesus and Kundun’s troubled Dalai Lama, Scorsese’s mortals grasping at wisps of the divine. Plus, the dizzying lineup of interview subjects (Jane Birkin! Ravi Shankar! A pre-prison Phil Spector!) offers a revealing glimpse into Scorsese’s packed Rolodex. The rarefied heights of access in his nonfiction portraits incidentally confer the clearest notion of his status; Harrison’s widow Olivia didn’t even want to do a film about her husband, but couldn’t say no when Marty came a-calling. -CB

48. “The Neighborhood” (2001)

Thrown together in a hurry to coincide with the Concert for New York City post-9/11, this short sees Scorsese and a very young Francesca — still in a stroller — exploring the block of Elizabeth Street, between Prince and Houston, where he was raised (and which has changed as much in the last 20 years as it had in the previous 60). In dialogue with a number of his earlier films, it features rare footage of his immigrant parents previously seen in My Voyage to Italy, affectingly revealing the personal subtext of the Lower East Side melting-pot story he was making at the time, Gangs of New York, and pushing against the jingoism of the post-9/11 moment. – MA

47-46. Public Speaking (2010) / Pretend It’s a City (2021)

The first and third parts of the Fran Lebowitz Trilogy — lest we forget her cameo as a judge who’s simply not having it in The Wolf of Wall Street — allow Manhattan’s top public intellectual to sound off on a world changing so fast that the concept of a “public intellectual” may soon cease to exist. Earth’s preeminent female alte kaker elevates complaining to an art form with her hot takes on real estate hassles, pedestrian right-of-way and street-side book stands, in the process illustrating how central kvetching is to the Jewish way of life all New Yorkers passively absorb over time. Some scoffed at the three-and-a-half-hour cumulative total of the latter Netflix miniseries, but there’s no such thing as too much time spent hanging out with a singularly gab-gifted peddler of opinions. -CB

45. “Feel Like Going Home,” The Blues (2003)

PBS turned to Scorsese to coordinate the considerable undertaking of The Blues, a series of seven feature-length films on America’s native musical heritage from a heavy-hitter lineup collecting Wim Wenders, Clint Eastwood and Charles Burnett. He tackled the first installment himself, a sonic 23AndMe that starts as a tour of the Mississippi River Delta with guide Corey Harris, then traces its lineage back to West Africa for a lesson on early strains of tribal percussion and vocals. The same respectful, open-minded curiosity about foreign culture that brought about the Film Foundation and the World Cinema Project also molds Scorsese’s playlist here, an eclectic ensemble whose company and insight he graciously, gratefully appreciated as a rare privilege. – CB

44-43. The 50 Year Argument (2014) / Personality Crisis: One Night Only (2022)

In his two collaborations with co-director David Tedeschi (editor of earlier music docs like George Harrison and No Direction Home), the Big Apple’s favorite son pays homage to a pair of New York icons, one from the intellectual penthouse and one from the pop-cultural gutter. The 50 Year Argument glossily leafs through the history of the New York Review of Books as the august magazine celebrates a half-century of instructing uptowners on how best to project a heightened brow at cocktail parties. Personality Crisis joins New York Dolls frontmaniac David Johansen for an intimate birthday show at the Café Carlyle, during which the troubadour regales the crowd with anecdotes from his puke-flecked salad days in the punk scene. The spectrum of taste they jointly form does a pretty good job of capturing the allure of New York’s forced coexistence, by which paupers share the sidewalk with princes — and occasionally, as in Johansen’s case, become one. -CB

42. Shine a Light (2008)

Scorsese’s soundtracks have drawn so liberally from the Rolling Stones’ catalog that it was only fair the director should give something back. This monument to the band most closely synonymous with rock ’n’ roll itself frames them as masters of their domain, dropping in on New York’s Beacon Theatre from a stadium run to show a crowd including Hillary and Bill Clinton that they still got it. (Mick Jagger does this in part by grinding with Christina Aguilera. What a time, the Bush years!) The performance numbers have plenty of pep, but completists will get the most out the interstitial bits in which Scorsese turns the camera on himself as he pieces together the elaborate mechanics of shooting live music. It’s an edifying lesson in the relationship between creativity, craft and their confinements; we watch Scorsese talk about the desire for lightweight mobility, and then we see analog film’s most loyal servant take up a digital camera for the first time in his career. -CB

41. Boxcar Bertha (1972)

No one’s idea of either a Martin Scorsese crime classic or a Roger Corman exploitation delight, Scorsese’s second feature combines his sensibility with Corman’s genre requirements to produce a strange, but strangely compelling, hybrid of the two. Barbara Hershey stars as a rail-riding orphan who stumbles into a Depression-era robbery career, and you might watch this 88-minute B-picture wishing that a later-period Scorsese had done a lady-outlaw drama. Still, this goes pretty hard; Scorsese gives the low-budget violence an extra jolt of vivacity that makes it all a little more intense and troubling than it likely would have been in another’s hands. Its low ranking among his feature films is understandable, but probably undersells the film’s entertainment value. – JH

40-38. NYU Student Shorts: What’s a Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Place Like This? (1963), It’s Not Just You, Murray! (1964), The Big Shave (1967)

Scorsese’s first two student films showcase his direct-address cinema in chrysalis — both are anchored by fast-talking narrators but vibrant, busy to the point of overloaded, with cutaway gags and resourceful techniques, never stopping, as his adventuring leading men never stop. The first film takes a hip, psychoanalytically informed look at a neurotic writer’s hangups, sexually or otherwise, betraying the influence of a burgeoning counterculture newly in touch with its feelings, which Scorsese would invite closer to home with his madonna-whore-complex debut (see immediately below). The second, which Scorsese has said was inspired by the late-cycle Jimmy Cagney gangster picture The Roaring Twenties, travesties an old Hollywood genre. Taken together they establish Scorsese as both movie-mad and in thrall to private obsessions. The Big Shave, about a handsome, shirtless young man cutting his face up in front of a bathroom mirror, declares itself a Vietnam allegory but also more broadly captures the shock of violence, the allure of the visceral, the erotic charge of self-flagellation. It’s Scorsese’s essence, as concentrated as the bright-red movie blood that drips down the man’s face and circles the drain. – MA

37. Who’s That Knocking at My Door? (1967)

The young ex-Marine Harvey Keitel is so cute in Scorsese’s first feature, started in his student days. Dimpled, flirty, abashed, so sympathetic in his skinny ties and neatly parted hair, Keitel projects the kind of naive youthful tenderness that so often goes hand-in-hand with shockingly retrograde sexual hang-ups, as here: his J.R. is caught between time-killing adventures with the fellas and the possibility of an adult relationship with a woman whose troubled sexual history he struggles to reconcile with his cradle Catholicism. It’s the template onto which Mean Streets would graft the crime genre, kick-starting Scorsese’s half-century on the A-List, but Who’s That Knocking also emerges out of the New York underground of the ’60s. Shot partly in 16mm, with New Wave-y in-camera flourishes, stolen locations, jarring psychologically motivated edits, and an autobiographical, neurotic script, it’s a mix of early Cassavetes and James McBride. – MA

36. Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese (2019)

Of all the movies to have Scorsese’s name in the title, this feels like a particularly odd choice. The material included in this Netflix extravaganza is mostly divided between footage originally shot in the mid-1970s, in and around Dylan’s legendary Rolling Thunder Revue tour, entirely apart from Scorsese; and contemporary interviews (some with actors playing characters or fictional versions of themselves), also not shot by Scorsese. It sounds like the project was the brainchild of Dylan’s manager Jeff Rosen; at minimum, he approached an enthusiastic Scorsese with the job of assembling it all into a proper film and conducted the interviews himself. This is not so different from the production of the previous, PBS-released Dylan doc No Direction Home, but Rolling Thunder Revue’s mixture of fact and fiction is so much more conceptual and rambling than the earlier film, and so in keeping with Dylan’s playful treatment of artifice and image-making, that it’s hard to detect to how much of Scorsese’s authorship really shaped the final film. Of course, that’s perfectly appropriate for the project at hand — for better and worse. The flashes of secret fiction, including faked anecdotes from Scorsese’s Casino star Sharon Stone, aren’t really detectable to the casual viewer, so the effect can come across as an elaborate inside joke for people who already know the real stories. Does it matter that Dylan takes a characteristically obtuse angle on his own history, especially when the performance footage is so beautifully captured and selected? Not really; for plenty of fans, this will be more feature than bug, and why would a non-fan be throwing on a 140-minute deep-dive on a highly particular era of Dylan’s career? It may just be that the Rolling Thunder live performances are so terrific that not even Martin Scorsese or Dylan himself can really improve upon them. – JH

35. “Mirror, Mirror” (Amazing Stories, 1986)

Scorsese and his longtime friend Steven Spielberg have intersected professionally a number of times; at one point, it looked as if Scorsese would direct Schindler’s List and Spielberg might do Cape Fear, until they swapped projects, and this year they’re both credited producers on Bradley Cooper’s Maestro. But more direct creative collaborations between the two are understandably fewer. (Why have two of the best to ever do it working together on a single project? Seems redundant.) But in 1986, Scorsese directed this episode of Spielberg’s ill-fated anthology series — from a story credited to Spielberg himself. That story is a simple one: a horror author (Sam Waterston) who claims to be unbothered by his terrifying creations is haunted by a scary cloaked figure who appears to him in reflections, but no one else can see. That’s about all there is to it; it really is mostly Scorsese figuring out inventive ways for Waterston to catch a glimpse of his menaced reflection (mirrors, yes, but also reflective lenses and eyeballs!), with nightmare logic in place of carefully calibrated Twilight Zone irony. Beyond being a rare chance for Scorsese to flirt with a genre he’s never full-on tackled — the figure (played by a young and unrecognizable Tim Robbins!) is like something out of a Universal horror picture — it’s also amusing as a means of Scorsese to playfully reckon with the idea of an artist affected (or not) by the violence he explores in his work. Minor stuff, to be sure, but a vigorous 24-minute exercise that puts plenty of prestige TV to shame. – JH

34-33. “Bad” and “Somewhere Down the Crazy River” music videos (1987)

The Scorsese-directed accompaniment to the hit that reintroduced a newly street-tough Michael Jackson was no mere music video, but in its 18 minutes of West Side Story allusion, a certified work of cinema. MJ plays a city boy gone off to a posh private school in the ‘burbs, returning to his old partners in crime (including a pre-fame Wesley Snipes) only to find that he can no longer inhabit that demimonde. A reconfiguration of the time-tested Scorsesian themes of male friendship, inbred misbehavior and ambivalence about both, this short-form marvel acquainted the rock aficionado with a youth-oriented Top 40 and sent a generation of kids rushing to buy leather jackets. Though this bit of miscellany slots most meaningfully into his filmography in its NYC location shooting; the fact that one dance sequence took place on a defunct platform at the Hoyt-Schermerhorn A/C/G subway stop now flashes across MTA trains’ in-car ad screens as trivia. I can think of no tribute more moving. (He also busied himself in the year between The Color of Money and The Last Temptation of Christ with a video for Robbie Robertson, leader of The Band and his longtime friend. It’s pretty standard, mostly just jewel-tone lighting of singing and shredding, until Robertson starts furiously making out with background vocalist Maria McKee.) –CB

32. Bob Dylan: No Direction Home (2005)

Years in the making before Scorsese even boarded the project, this documentary follows the first five years of Bob Dylan’s career, from his New York City days in 1961 to his motorcycle crash in 1966, with such breadth, depth and detail that hardcore fans might pine for another 10 installments to piece together the next five or six decades. (The Rolling Thunder Revue movie, also featuring interviews and footage handed to Scorsese for assembly, is part sequel, part B-side, part spoof.) In the context of Scorsese’s filmography, it’s a testament to his rigorous dedication to the artists he admires; there’s little intro-to-Dylan shaving of details or dumbing-down of context that sometimes characterizes more tribute-oriented documentaries. Scorsese does peek out at the beginning of two feature-length installments, where he provides Dylan’s voice, reading a bit of the musician’s ill-received speech after receiving an award from the Emergency Civil Liberties Union — a fascinating glimpse into the kinship Scorsese may feel with Dylan over a mutual ambivalence toward institutional approval (in a project that was released during Scorsese’s peak Oscar-suspense years, shortly before he finally won Best Director for The Departed), or maybe just another Dylan-style weirdo flourish. – JH

31. Kundun (1997)

Of course Christopher Moltisanti liked this life-and-times biopic of the Dalai Lama, another tireless existential searcher forever struggling with the limits of his own enlightenment. Chrissy yells it like he’s the only one who feels that way, and it’s true that pop artist Scorsese’s comparatively esoteric sojourn to Tibet went little-seen in 1997. (The grosses weren’t helped by a modestly-advertised run from Disney, for which the company apologized to the Chinese government within a year as they drew up blueprints for Shanghai Disneyland.) But underneath Phillip Glass’ kaleidoscopic compositions and Roger Deakins’ psychedelic cinematography informed by the intricacy of Buddhist monks’ sand mandalas, there lies the simple beauty of belief. In this film, as in Silence and Killers of the Flower Moon, Scorsese extends a profound respect toward anyone willing to self-sacrifice for religious faith, irrespective of which god they pray to. At a certain point, they’re all pretty much the same, the Dalai Lama yoked with the same Atlantean pressure of terrestrial holiness placed on the shoulders of Christ. In the eternal tug-of-war between profanity and sanctity, Scorsese devises a true global language. -CB

30-28. A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through American Movies (1995), My Voyage to Italy (1999), A Letter to Elia (2010)

“I still consider myself a student,” Scorsese says at the end of his documentary about the history of American cinema from the silent era to the start of his career. Teeming with references and overflowing with passion, his super-sized clip-show documentaries, about Hollywood and postwar Italian cinema, are, like his film restoration and preservation nonprofits, acts of love and monuments erected lest we forget. As he talks you through what you’re seeing, Scorsese shares his own moviegoing and memories offers vernacular readings through the prisms of stylistic analysis, genre studies, industrial history, sociological critique and auteurism (and biographical readings, as in his Kazan epistle of PBS’s American Masters, codirected with Kent Jones). He’s so sincere — he offers as entertaining and accessible an introduction to film art as you could ever convince your favorite young relative to sit through with you. – MA

27. Hugo (2011)

Given that it’s the first and so far only family film from a guy better-known for exorcising his demons onscreen, Hugo’s general lack of dramatic tension is almost touching. Adapting Brian Selznick’s (admittedly un-thrilling) illustrated kids’ novel, Scorsese neither over-intensifies the material to make it fit his style nor gives in to the contemporary kid-adventure tendency towards jostling antics; even the obligatory chase scenes are more elegant than Spielberg-style visceral. What’s actually, genuinely, deeply touching is Scorsese making a sweet-natured fable about film history and preservation, using big-budget resources (including, in its original theatrical release, masterfully deployed 3-D) to recreate (and in some cases, simply rebroadcast, in all their glory) early flights of silent-film fancy, creating windows within windows to a combination of shared and imagined past. There are plenty of movies for or about children that are secretly better for adults; if Scorsese doesn’t unequivocally master both audiences here, well, program Hugo in a film festival alongside the Spike Jonze Where the Wild Things Are and the Wes Anderson Fantastic Mr. Fox. – JH

26. Shutter Island (2010)

Even the most devout Scorsese-ites will concede that as dooly appointed federal mahshal Teddy Daniels, Leonardo DiCaprio’s really chewing on the accent he had under control in The Departed. And fine, yes, the third act gets bogged down in exposition that turns what should be a thrilling denouement into a series of inert monologues. But before that, we get the master returning to the pulp mode of Cape Fear for a waking nightmare that morphs into a shattering meditation on guilt, self-preservation and the psychological scarring left over from the second World War. Emulating Val Lewton’s empathy for the macabre and Hitchcock’s expert manipulation of tension and effect, he elevates the B-movie to the level of high art and collapses the distinction between them; there’s genuine horror in the recurring hallucination of a deceased wife disintegrating as ash in her bereaved husband’s arms, just as there’s poetry in the Caliban-like abomination locked in the basement. -CB

25. Cape Fear (1991)

The most incongruous of all Amblin Entertainment productions came about from the Movie Brats swapping projects mid-development — this is the movie we got instead of Scorsese’s Schindler’s List — but despite Spielberg’s early involvement, the Hitchcockian flourishes, including Saul Bass titles and a brazen Psycho shoutout, make this thriller remake feel very De Palma indeed. As vengeance-crazed ex-con Max Cady, Robert De Niro is Nietzschean, Southern-fried, absolutely shredded — and perilously close to parody, but he also helps brings out spontaneous and sympathetic performances from Juliette Lewis and Illeana Douglas as two touchingly multidimensional victims of male rage. – MA

24. The Aviator (2004)

Contrary to the backlash out of Newport Folk, going electric did not end Bob Dylan, and it didn’t do a damn thing to make Martin Scorsese any less himself. He warmed up to the technologies of the 21st century in his colossal recounting of Howard Hughes’ rise and descent into madness, but only to get closer to the essence of his beloved celluloid, layering computerized effects over analog filmstrips to ape extinct two- and three-strip Technicolor aesthetics. His meticulous, handsomely-funded tinkering forms a pleasing metatextual rhyme with Hughes’ obsessive compulsions, a self-destructive diligence pondered here as the toll all directors of insatiable ambition must pay for excellence. Goodfellas and Casino both approached the three-hour mark, but the profligate sprawl of this all-the-trimmings period piece stands as the clearest signpost that Scorsese’s career had entered a new era of fruitful indulgence, the first of his films embracing its odd ends — Cate Blanchett’s polarizing Mid-Atlantic accent, Leo scarfing ice cream in the nude, Gwen Stefani dropping in as Jean Harlow — sticking out every which way. -CB

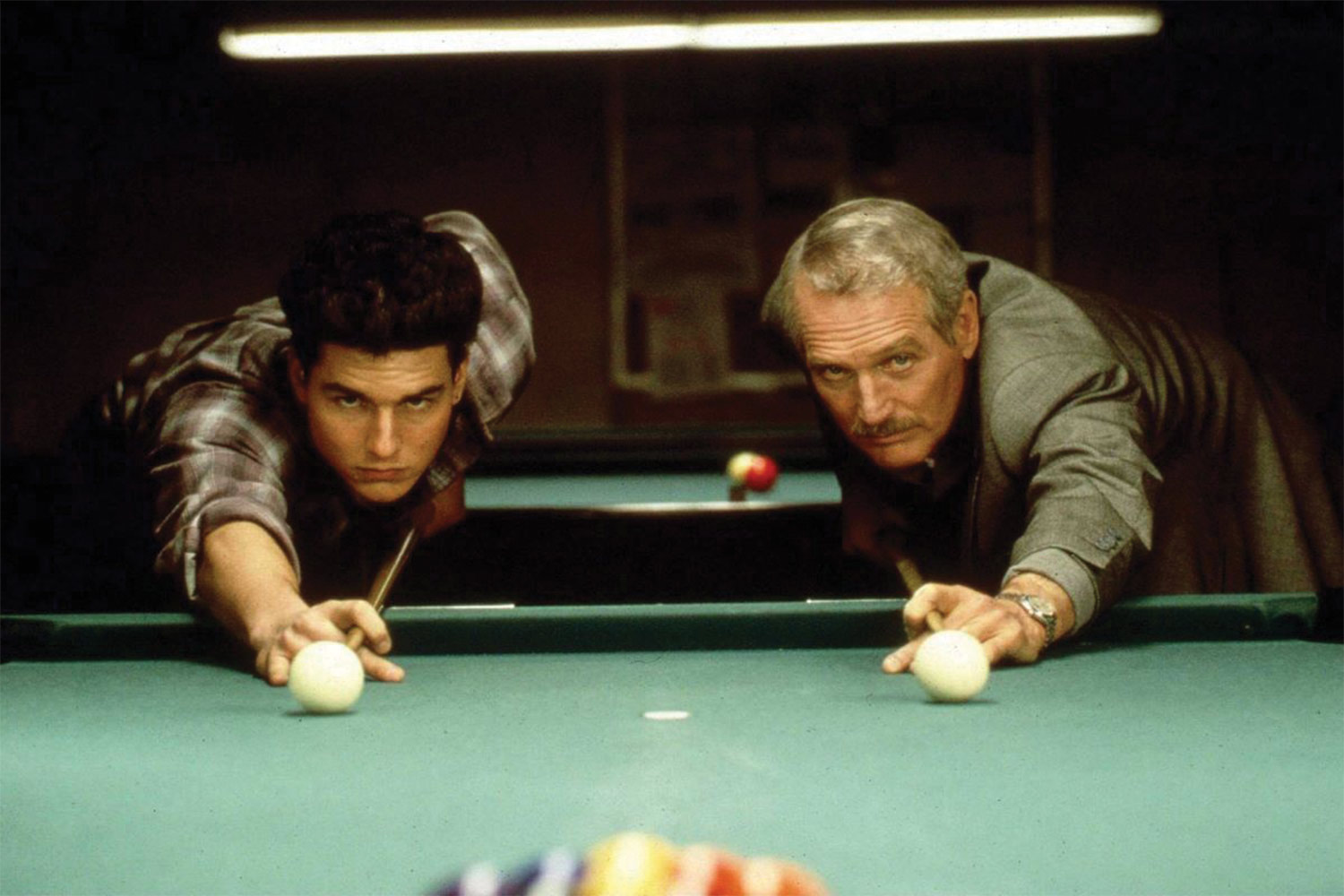

23. The Color of Money (1986)

Remember when the sound of a paycheck cashing could somehow feel musical? Most of today’s auteurs venture into one-for-them arrangements with any personal vivacity drowned out by the groan of heavy franchise machinery; no wonder most of our best simply avoid it entirely. The Color of Money… now there’s some franchise machinery you could set your watch to, with the satisfying billiard-breaking snap-crack of a title perfectly evoking its own mercenary aims. Of course, the idea in 1986 wasn’t to jumpstart the Hustler Cinematic Universe, but this still a two-decades-later legacy sequel luring a beloved actor back to a well-loved role in tutelage of an incoming superstar, directed by someone who had nothing to do with the original. With the fullness of time, though, this paycheck gig gives us the only movie where Martin Scorsese directs Paul Newman (reviving his Fast Eddie Felson), and likely the only movie where Scorsese will direct Tom Cruise (appearing in, frankly, the vastly better of his two 1986 sports-like dramas about a young hot-shot). In other words, it is scientifically formulated to get you to stop on it when channel-flipping on a Sunday afternoon, the ultimate old-timer-still-got-it flex, made by a director who was all of 44 at the time. I know in my heart that Scorsese has made a dozen or two “better” movies than this, and honestly, I still want to stop what I’m doing and watch it right now; what’s a better form-follows-function hustle than that? Scorsese has since referred to the movie as an exercise in making a conventional Hollywood studio picture, an experiment he’d never repeat today (or even 20 years ago) with such limited time left. Hey, fair enough, as long as we get to keep this one. – JH

22. Gangs of New York (2002)

Met with equal acclaim and derision upon its much-delayed release and eventually more-or-less redesignated as one of Harvey Weinstein’s less actively criminal violations — he essentially refused the 200-minute running time Scorsese has finally exercised on his last couple of projects — Scorsese’s draft of 19th-century U.S. history has some uncharacteristically ragged patch-ups (some clunky narration, weird bits of fast-motion transitions) but also a sense of gruesome majesty that makes it well worth revisiting. Scorsese’s previous fictionalized forays into American history tended to take a narrower view, at least superficially, whether through the life of Jake LaMotta or the development of Las Vegas casinos. But his electric yet digressive style is remarkably well-suited to the sprawl of events, details and anecdotes of 19th century Manhattan, as when he depicts rival volunteer fire brigades brawling with each other while the building behind them burns down or observes as gang leader Bill the Butcher (Daniel Day-Lewis) blithely discusses with Boss Tweed (Jim Broadbent) the optimal number of public hangings to keep the citizens of New York in check. The horror is mitigated — maybe not always appropriately — by the luxe filmmaking, including vast Dante Ferretti sets built at the Cinecittà Studio in Rome. Flaws and all, it’s spectacle on the level of his pals Spielberg, Lucas and Coppola. – JH

21. Bringing Out the Dead (1999)

Has Scorsese’s talent for matching pop music to harrowing images been overshadowed by Tarantino, period pieces and too many Rolling Stones cuts? In his most recent years, the director’s interest in rock and roll feels more sequestered in his documentary work, but Bringing Out the Dead offers multiple great and underseen examples of what the man can do with guitar, drums and bass, even if he’s not technically the one playing the instruments (or depositing licensing fees into the Stones’ account). This Paul Schrader-penned story of hellish ambulance-driving nights in Hell’s Kitchen features some of his best needle drops. The reverb of R.E.M.’s “What’s the Frequency, Kenneth?” blares alongside the ambulance sirens; the Clash’s “Janie Jones” hops up a wired blur of emergency calls; the lilting, maddening beat of UB40’s “Red Red Wine” wafts through a crime scene as an EMT discovers a man impaled on a balcony in the apartment below. That EMT is played by Nicolas Cage — maybe the perfect actor to preside over such an eclectic setlist for such a grimly exhilarating exploration of how grief and suffering can feel, at times, as relentless, inescapable and noisy as a soundtrack. – JH

20-19. ItalianAmerican (1974), American Boy: A Profile of Steven Prince (1978)

Between Mean Streets and Taxi Driver, sporting a beard to make him look older and more bohemian, Scorsese returned to his parents’ apartment on Elizabeth Street, sitting down opposite their plastic-covered sofa to ask about his family history while he still could (and to write down his mother’s recipe for meatballs and gravy). Their memories of the old country and loving bickering make for cozy viewing, and maybe a stifling experience — the film invariably screens alongside Scorsese’s portrait of roadie, junkie and raconteur Steven Prince, full of horseplay and wild anecdotes, like the adrenaline-shot story borrowed by Tarantino in Pulp Fiction, and watching the two together feels like busting out of your family’s house the day after Thanksgiving to have a drink with the wildest friend you can find. The double feature is a vivid picture of generational divides in immigrant families, of the bipolar pulls of home and reinvention. – MA

18. Casino (1995)

Let’s talk about the thing where the aggro-sensitive babies who get everything they want out of cinema via superheroes characterize Martin Scorsese as purveying the same group of tired phallocentric gangster clichés over and over. (After all, who could compete with making 20 superhero movies, then doing one starring a girl?) I’d be happy to dismiss this sentiment entirely, but I admit, there probably is a popular conception of Scorsese as a mob-movie guy. (A little odd, given how many of his movies actually made more money than Goodfellas, but there may have been a long tail on that one.) To the extent that you can locate some core of truth in that idea, it can probably be traced to the fact that five years after Goodfellas, Scorsese made another mob picture set in a similar time period with the same screenwriter and two returning actors — and no, Casino isn’t as great. It’s longer but less propulsive, chattier but not as funny, more violent but with less memorable context for that violence. And yet, in addition to being wildly entertaining in the way of dueling De Niro and Pesci voiceovers, Casino also feels more connected to several of the ambitious Scorsese movies that followed it, even though many of them are easier to differentiate from Goodfellas. Casino converges Scorsese’s crime chronicles with American history, something he would do even more forcefully in Gangs of New York, The Irishman and Killers of the Flower Moon. (Casino is basically those movies for the era of the two-tape VHS release.) The mob stuff is almost incidental, because once the house gets set up, it obliterates everyone in its path, even the ruthless capitalists who think they’re running the show. Sure, drugs and ego get in the way, too, but there’s a rapaciousness here absent even in Goodfellas, where made-man status bundles up with social capital (buy your status local!) that the characters here seem largely disinterested in accruing, beyond its ability to make them more actual money. If you thought Rupert Pupkin’s imaginary talk-show gigging was eerily joyless, wait until you get a load of the score-settling vanity project that is The Ace Rothstein Show! In some ways, this is less a reiterative gangster picture than his first true historical epic (albeit it from the cloistered vantage point of Vegas). After all, if you’re going to grapple with American history, you have to follow the money, whether that means profiling the mafia or finance sharks. Fitting, then, that Casino once held the all-time raw-number record for utterances of the word “fuck” in a fiction feature film, and has since been surpassed by The Wolf of Wall Street. – JH

17. New York, New York (1977)

After the triumph of Taxi Driver, Scorsese moved on to his great folly, the movie that nearly killed his career, and himself. Like the other iconic New Hollywood bombs, New York, New York is less a movie than one man’s dream of the movies, brought almost to life in its impossible grandeur: an MGM-style musical made on a swooningly expensive retro backlot, a new flourishing of Old Hollywood glamour that Scorsese picks at like a scab. Following the personal and creative relationship between Robert De Niro’s volatile, uncompromising saxophonist and Liza Minnelli’s romantic, up and coming singer, Scorsese, at a restless moment in his career, is torn up over the binaries of art and commerce, authenticity and artifice, men and women, and — thanks to the emotionally bruising contrast in acting styles between the Method actor, with his thrusting, insinuating improvisations, and Judy Garland and Vicente Minnelli’s daughter, with her quavering diction and huge frightened eyes — cinema’s future and past. – MA

16. The Last Waltz (1978)

If Stop Making Sense is the great American concert film because it’s a great narrative film, following an unformed individual consciousness as it awakens to the glorious diversity of the world, then the other great American concert film is also a great narrative, and classic Scorsese (as Stop Making Sense is classic Demme). As The Band (often druggily) reminisce about a hedonistic, exhausting life on the road, and bring their old collaborators on stage to close out their career and an era of American music,The Last Waltz becomes a rueful tribute to the joys of hanging out with your sketchy friends, a study in competing egos, a document of dangerously oversatiated appetites — and, through all those redemptive harmonies, a statement of belief in the power of art to transcend our mortal flaws. As then-33-year-old Robbie Robertson explains his reasons for breaking up the band, his precocious midlife crisis serves as an advance warning of the Boomer self-mythologization that would dominate the next 45 years (and counting!) of American cultural and political life — and imbue Scorsese’s autumnal films with the profound contrasting pulls of nostalgic yearning for the indulgences of a simpler time and guilt over the accumulation of irreversible decisions. Call it “The Weight.” – MA

15. Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974)

Scorsese’s films contain some terrific female characters, but the number that really adapt their sustained point of view is far fewer — and that’s OK, given what Scorsese is exploring in so many of them. Then again, based on Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, he’s a sharp observer of experiences outside the sphere of toxic masculinity (or, more accurately, merely adjacent to it). Ellen Burstyn plays a newly single mother forced to put her hopes of a singing career on hold and take a waitressing job in Arizona to support her young son. The episodic story — this is inarguably the only Scorsese movie to inspire a nine-season sitcom, and it’s easy to see how that transition was made — accumulates real-life textures, details and truths at a steady clip. The pace is decidedly different from Scorsese’s more kinetic later features (or Mean Streets the year before), but his eye for evocative images and ear for human behavior remain recognizable even in this quieter context. One moment that lingers with me as a parent is a car scene where Alice’s son Tommy labors to recount a vulgar playground joke until she cries frustrated tears of desperation, she wants so badly for her beloved kid to just drop it. It’s as raw and darkly funny a mother-son moment as I can recall in American movies. – JH

14. The Departed (2006)

It takes a particular talent to make a dorm-room-poster normie classic this deep into such a multifaceted career, and a greater one to have the movie in question hit just as hard as its less-loved siblings. Apparently the making of The Departed soured Scorsese’s relationship with Warner Bros., and it’s easy enough to see this Infernal Affairs remake as a mainstream play just accessible enough to net Marty that for-hire Oscar. But goddamn,The Departed is such a terrific, tough cops-and-criminals picture regahdless, zeroing in on the “right” side of the law that has never been much of a focus in Scorsese’s other crime movies, and finding it equally fraught with guilt and moral contradictions. It’s also the movie that essentially made Leonardo DiCaprio’s adult movie career, not by shedding his boyishness entirely but shredding it into the frayed edges of a wounded kid, concealed by his undercover assignment: pretend to be the criminal everyone always assumed he’d become anyway. It’s perfectly fitting that one of Scorsese’s starriest movies — Leo! Damon! Nicholson! Baldwin! Wahlberg, ascending to an Oscar nomination! — surveys the psychological toll of long-haul deception. – JH

13. The Last Temptation of Christ (1988)

Scorsese’s most realistic movie — or at least, with its budget-restricted illustrated Bible scenes playing out in minimally embellished Moroccan desert exteriors, his most naturalistic — treats Jesus as a very Scorsesean figure, tormented by his own lust for worldly life. The crucifixion is as garishly violent as his gangster films, deliriously saturated with sensation — so much so that when the Son’s sacrifice is accomplished the movie is simply spent, the image going wonky like the celluloid is running out of the projector. Jesus’s followers are played by musicians, experimental theater people and assorted familiars from Scorsese and Willem Dafoe’s normal milieus, giving a dog-eared tenderness to what becomes yet another Scorsese film about hanging out with the boys; the relationship between Jesus Christ and Judas Iscariot is, in Scorsese’s telling, at its heart simply a depiction of male friends bonded by loyalty and riven by betrayal. – MA

12.“Life Lessons” (from New York Stories, 1989)

One of the greatest on-screen age-gap relationships is the one between Nick Nolte’s leonine, shambolic, heroic painter and his uncertain but ambitious assistant and ex-lover Rosanna Arquette — as his insecurities, over his art and his waning domination of her, and her residual feelings for her benefactor and simultaneous realization that he’s running out of things to teach her, cohere into a clear-eyed, hardly uncritical inquiry into sex, power, talent and mentorship. Scorsese draws on the movements then bringing national attention to New York City’s local art scenes — Nolte makes large-scale neo-Expressionist paintings in the Schnabel-Basquiat-Salle mode; as his romantic rival performance, Steve Buscemi, a downtown performance personality himself, plays a Bogosian-like monologist — as well as on the undimmed vitality of his favorite music. Scenes of Nolte painting, blasting Procol Harum and layering paint on canvas in a competitive fervor of invention, are a ripe portrait of undimmed creative libido. – MA

11. Silence (2016)

The 17th-century Japan of Silence is shrouded by a fog — rolling in off the ocean, closing off our field of vision and rendering distant figures and natural vistas misty and obscure — that could be mortality itself, a veil of ominous uncertainty drawn snugly around the material world. As Portuguese priests Andrew Garfield and Adam Driver risk (or court) martyrdom to spread the Gospel (or a version of it) to Japanese peasants fearful of their feudal government and thirsty for transcendence, Scorsese conjures images with an austere grandeur befitting the film’s sophisticated treatment of imperial coercion, arrogant zealotry, political pragmatism and spiritual doubt. Drawn to familiar themes — Shusaku Endo’s source novel was first recommended to Scorsese during the Last Temptation of Christ controversy — Scorsese also demonstrated, via the indelible performances by millennial leading men Garfield and Driver, and Japanese cinema icons Issey Ogata, Tadanobu Asano and Shinya Tsukamoto, his continued openness to new colors on his palette. – MA

10. Mean Streets (1973)

The quote attributed to Scorsese by Bong Joon-ho at the 2020 Oscars — “The most personal is the most creative” — begins to explain his first mature film, in which he takes his memories of the old neighborhood and embellishes them into the stuff of legend. Building on the wall-to-wall pop soundtrack of Kenneth Anger’s underground (Tijuana) Bible Scorpio Rising, Scorsese with his Ronettes and Rolling Stones needle-drops evokes a shared history, the common dreams of a neighborhood and a generation — as well as the restless, sexually charged energy of his young subjects. As the magnetic fuckup Johnny Boy, Robert De Niro energizes every scene partner, escalates every situation, ducks every call to responsibility with his jittery, encroaching physicality and savage laugh. He’s simultaneously a bracing gust of street-level realism and a larger-than-life highlights-only version of himself — just like the film, with its shabby, wintry Little Italy exteriors and ultimate operatic tragedy. – MA

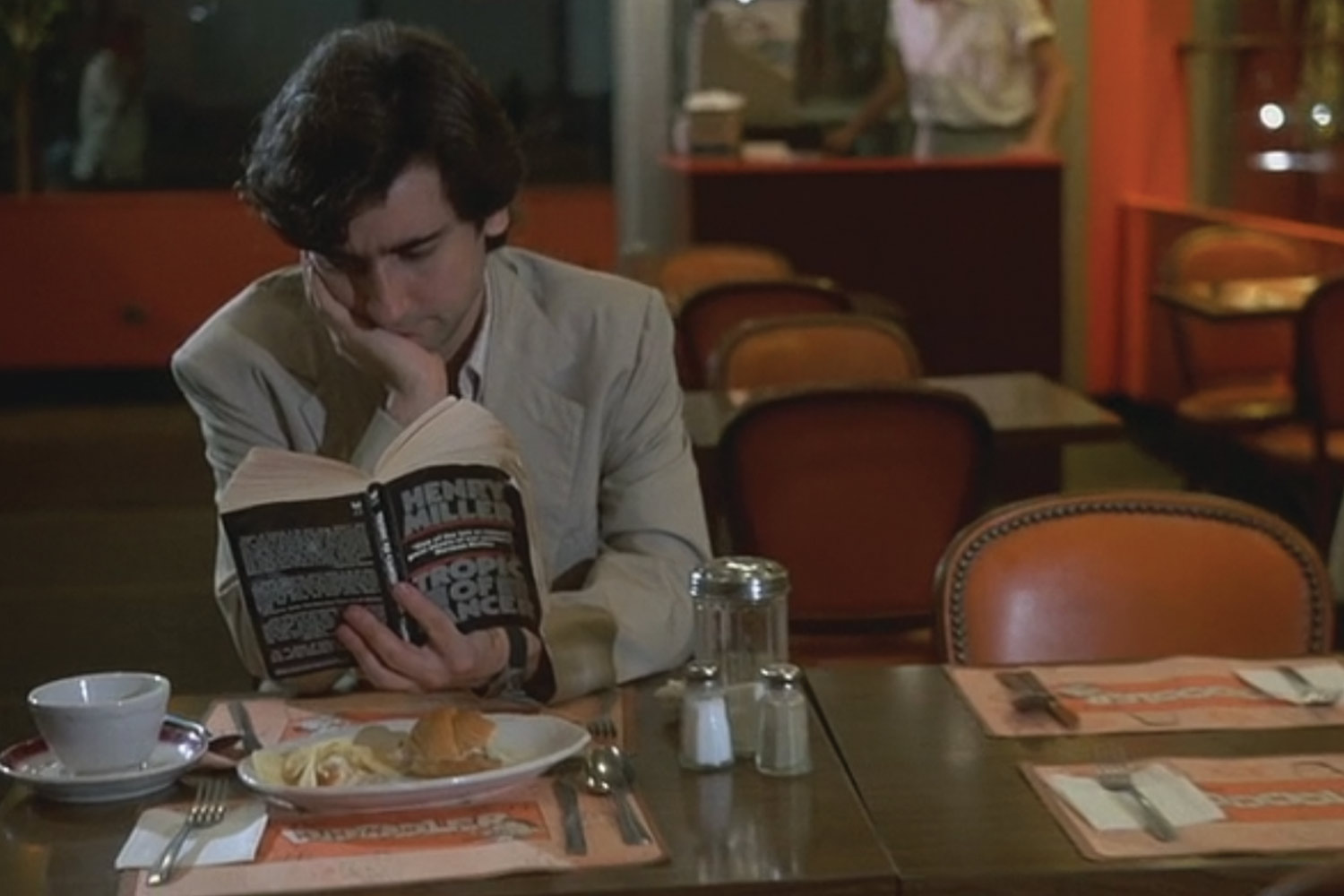

9. After Hours (1985)

This comedy of sexual frustration follows a very contemporary type: Griffin Dunne’s Paul Hackett, who fancies himself an intellectual despite his bullshit computer job. A Reply Guy avant la lettre, Paul bonds with a way-out-of-his-league Rosanna Arquette over a Henry Miller book and follows her downtown, on a weeknight ramble into a milieu populated by kinky artists, surly service workers and street weirdos. Paul’s fish-out-of-water odyssey evokes the transformation of Scorsese’s native lower Manhattan, in the wake of White Flight, from a bustling family neighborhood into a spooky bohemia, and his own rise from the cutting edge to the establishment. Think of it as a single-set farce with the entirety of SoHo as its stage — the glow of streetlights bounces off glistening cobblestones, isolating Dunne like he’s a stage actor in a follow-spot. In one nightclub scene, he’s also literally captured in a spotlight — operated by Scorsese himself, both an expert metteur en scène and a capricious God making sure every element of the plot pays off to thwart, harry and torment his protagonist. – MA

8. The Age of Innocence (1993)

For all their effortful performance of masculinity, gangsters sure are gossipy old biddies. Too many wiseguys have met an untimely end because they relayed or just chuckled at the wrong rumor, a delicate system of scuttlebutt etiquette that takes a central role in Scorsese’s anomalous Edith Wharton adaptation. The setting in New York keeps him close to home, and the ensemble of social climbers wield catty zingers like submachine guns as they maneuver against one another to amass status and influence, but trading bullets for bon mots brought out an unprecedented streak of romantic rapture in a filmmaker who’d often looked on love as a dysfunctional symbiosis festering among the mismatched. As the well-heeled Newland Archer, Daniel Day-Lewis faces an impossible choice — between Michelle Pfeiffer and Winona Ryder, yes, but also between a woman he has every reason to cherish and a woman he craves beyond all reason. Awash in Powell and Pressburger dissolves, his inner conflict expands to spread across decades, and leads to one of the most poignant endings in Scorsese’s catalog of compromised victories and noble failures. -CB

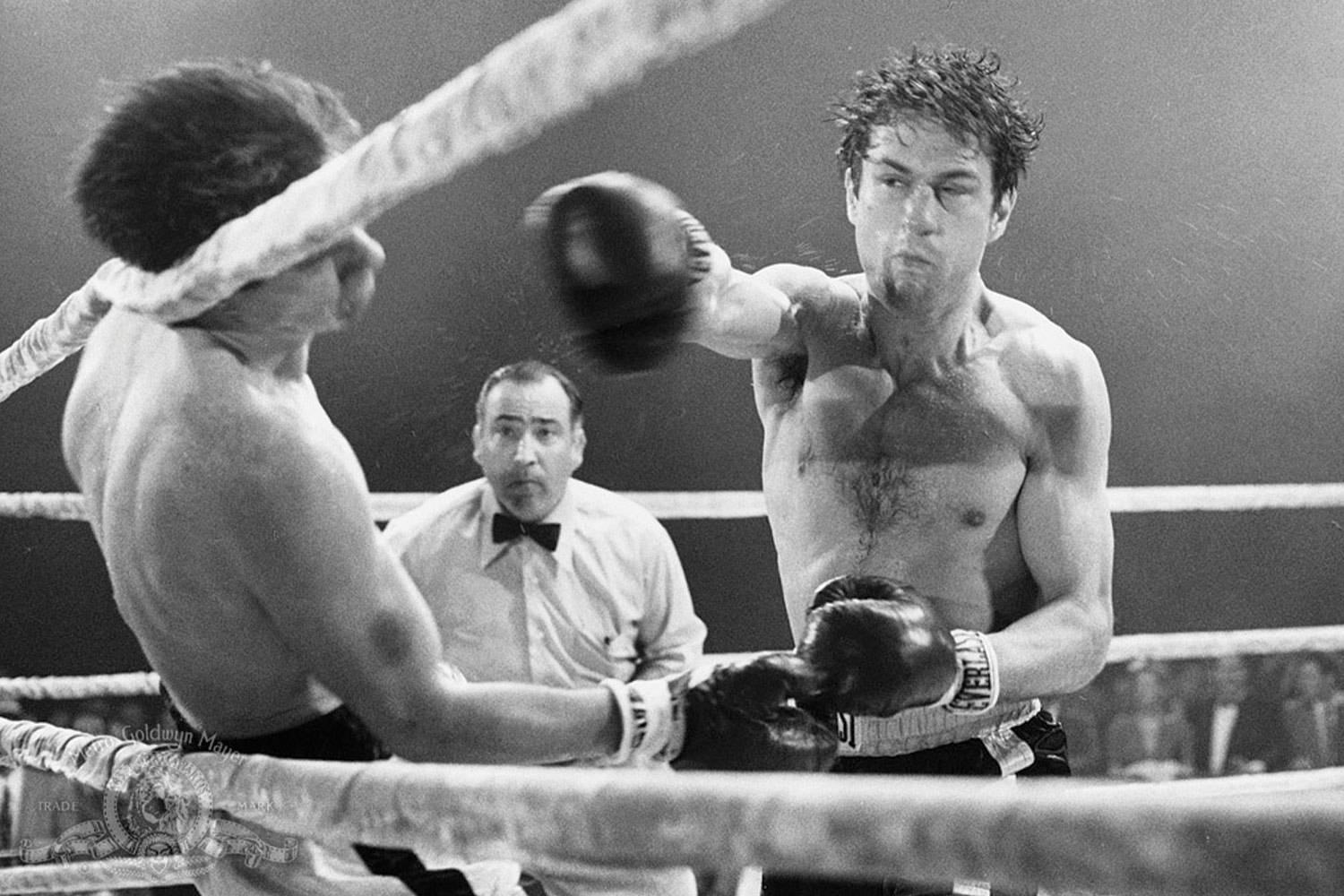

7. Raging Bull (1980)

The notion of Scorsese having a single consensus masterpiece has splintered in recent years, the 2022 edition of Sight and Sound’s definitive-ish greatest-of-all-time poll including three of his films. The ballad of kamikaze boxer Jake LaMotta sits way down at 129, but there’s a good reason that it regularly topped such lists in the years before the gates of canon-building were battered down. If Mean Streets played like proto-punk and Taxi Driver like minor-key jazz atop city noise, Raging Bull stood out for its refined yet brutal classicism, most literally in the swooning theme for strings and most overtly in the chiaroscuro elegance of the black-and-white cinematography. Though the Academy notoriously opted for the soothing bourgeois group therapy of Ordinary People, the apropos also-ran is still disarmingly tasteful, for the tale of a terminal rage addict who makes a living getting pounded into hamburger until he torpedoes his own life because he’s paranoid that his wife is having sex with his brother. Raging Bull wore its virtuosity on its sleeve in a way none of Scorsese’s others have, the clear product of an artist who believed kicking cocaine would either result in the greatest work of his life, or his death. -CB

6. Killers of the Flower Moon (2023)

Think about what other filmmakers are typically doing at 80. There’s pleasure, to be sure, in directors’ late-period works, but it occurred to me watching Killers of the Flower Moon that it doesn’t really register as late-period Scorsese, at least not in the usual sense of distilling a director’s obsessions to their purest form, or indulging them with a newfound, well, reflectiveness or pokiness; take your pick. Flower Moon does share some common ground with the more traditionally “late” The Irishman, in that they’re both three-and-a-half-hour period dramas that make excellent use of Robert De Niro, using timed micro-bursts of Scorsese’s trademark kineticism to become almost methodical in their exploration of American moral rot. And, sure, you could take either movie as a career sum-up; this one even brings De Niro and DiCaprio together with a steely female lead (Lily Gladstone), combining multiple favored Marty subjects into one narrative, in this case a sloppy but brutally effective conspiracy to murder members of the Osage tribe in the 1920s after they unexpectedly struck oil on the land where they were consigned. Yet Killers of the Flower Moon plays less like an elegy than The Irishman does, even as its creative evolution brings it to a place unlike any other in Scorsese’s filmography. At some point, the film was supposed to hew closer to the narrative of the nonfiction source material, which includes a fair amount of material about the birth of the FBI. A reconfigured version casts DiCaprio as the typically ragged, conflicted bad guy, killing members of the same Osage family he’s married into, while giving more perspective to Mollie (Gladstone), the Osage wife growing more suspicious of her supposedly loving husband. The story remains a procedural of sorts, exhuming an unusual marriage, the coziness between capitalism and racism, and a sense of national loss alongside the usual bodies. In the end, Flower Moon pivots gracefully into a consideration of that hoariest of high-minded recent clichés: Who gets to tell what stories, and why. It’s shot through with a bittersweet awareness that Scorsese can give a movie his all, spend $200 million worth of studio money, make an altogether masterful immersion in American crime, and still feel uncomfortably intimate, maybe even strangely small. – JH

5. The Wolf of Wall Street (2013)

There are multiple moments in Wolf of Wall Street where it seems like hedonist, stockbroker and criminal Jordan Belfort (Leonardo DiCaprio) is on the verge of explaining penny stocks, pump-and-dump stock schemes, IPOs and other attendant, more complicated matters of financial crime. A few concepts do get the voiceover treatment early on, but most of the time, Belfort interrupts himself and shrugs off the details as too complicated or dull to get into, as if anticipating (or preemptively dismissing) The Big Short, two years before Adam McKay stuck Wolf’s Margot Robbie in a bathtub, hoping to catch viewers’ attention long enough to tell them about subprime mortgage loans. Scorsese has used voiceover in plenty of movies, adding personal color to Goodfellas, hypnotic procedural explanations to Casino, and a glimpse inside Travis Bickle’s state of mind to Taxi Driver. Wolf of Wall Street may be the first time that a Scorsese narrator is addressing us purely because he enjoys hearing himself talk — which comes to an explosive head midway through the movie, when Belfort, forced by all sensible legal advice to take his money and run, turns his farewell speech into a rabid exultation of his own defiance. This isn’t really a movie about financial ins and outs; it’s about the sale. Belfort is selling himself to you, with one of America’s biggest movie stars as the irresistible hook, plus funny guy Jonah Hill and bombshell Margot Robbie as the value-adds. He may claim to enjoy drugs and fucking more than selling, but really, they’re so inextricably linked that the differences may no longer be discernible. Similarly, Scorsese’s not necessarily indulging in vicarious thrills by depicting the debauchery, slapstick hijinks and Hill improv runs at such length and volume, rather than depicting more of Kyle Chandler riding the subway like a schnook. He just understands, with the rueful clarity of a great artist, the hard sell. – JH

4. The Irishman (2019)

For Scorsese, “late style” starts here, with a standard set of midcentury gangsters rendered unfamiliar through the heavy regrets of geriatric exhaustion, the plastic texture of Netflix’s streaming compression, and the uncanny de-aging techniques Benjamin Button-ing Robert De Niro back into his youth. As a stoic hitman navigates the middle of a decades-spanning clash between the Mafia and union boss Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino, unlatching his jaw to swallow the film whole like a python choking down a gazelle carcass), what begins as another reverie about how the times were good until they weren’t eases into a more pensive and mournful place. As implied by the chyrons identifying each character and their eventual cause of death like a running joke, everyone’s story ends the same way, on a long enough timeline: with the big sleep. Scorsese has always given equal shrift to the terrible costs of crime along with its rewards, but never more harshly than here, unmaking a made man until all that remains is a remorseful husk. -CB

3. The King of Comedy (1982)

He’s a kidnapper and lunatic, but even so, it’s a shame Rupert Pupkin isn’t real. He’d have loved social media, YouTube, podcasting and every other newfangled enabler of the superfan delusions that have forced the phrase “parasocial relationship” into the public vernacular. A ruthlessly accurate portrait of the toxic, entitled relationship loyal followers cultivate with their celebrity idols, goosed with belly-shaking gallows humor and expressive flourishes of mental interiority, it’s enough to forgive the inspiring of Joker. The perfectly summative gag in which a pest on the sidewalk goes from worshipful adoration for late-night titan Jerry Langford (played by a startlingly reined-in Jerry Lewis) to hissing “you should get cancer!” in a minute flat remains a morsel of exceptional cruelty in a filmography that never stops plumbing the cracks in humanity. Scorsese may still be holding onto the memory of a New Year’s Eve Entertainment Tonight broadcast that dubbed this film “the flop of the year,” but modernity left him the last laugh. -CB

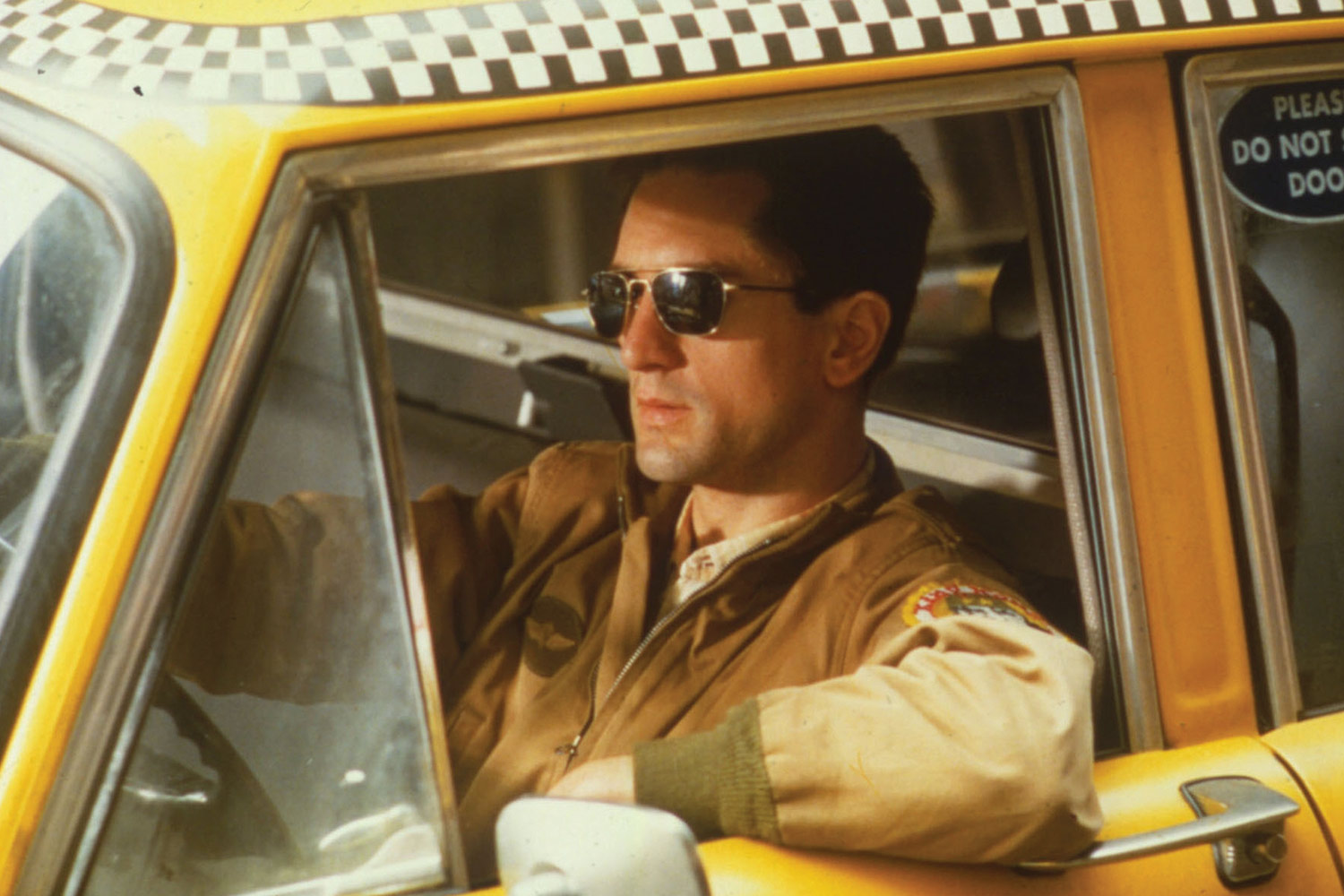

2. Taxi Driver (1976)

Like one of the Hitchcock zooms he likes to deploy to mark a significant moment, Scorsese’s genius-certifying Palme d’Or winner seems to get closer to and farther away from the present at the same rate. Though it still looms large in the conservative imagination, the image of Manhattan as a crime-ridden open sewer belching sulphur from the manholes to hell recedes deeper into history with each passing year of gentrification; meanwhile, the Travis Bickles of the world have multiplied like amoebas, their self-valorizing psychoses flourishing in the internet’s archipelago of adjoined isolations. And yet the most transcendent components in this jewel of grime exist outside of time: the exquisitely soul-sick score completed by Bernard Herrmann hours before he took his dying breaths, the combination of cringe comedy and pitiable vulnerability in Travis’ disastrous skin-flick date, the ferocious New Wave kineticism of the blood-streaked climax. The image of the pistol-brandishing, mohawk-clad Robert De Niro remains a dorm-poster staple both for his angry-young-punk muscularity and the mercilessness with which he exposes the rot underlying that fantasy. (Not incidentally, a few decades earlier, icon of disaffection Holden Caulfield imagined dying in a similar shootout.) After all these years, he’s still talking to us. -CB

1. Goodfellas (1990)

The most tiresome people on the internet will tell you that Scorsese only ever makes the same movie, about men whose toxic behavior he “endorses,” which seems to mean that he makes it look too fun, too enviable, too tempting. They’re mainly thinking of Goodfellas, our unanimous choice for his greatest film — and the thing is, they’re not entirely wrong. Because of course, it’s always the same story. The desire to sin is, you might say, the genesis of Western narrative. (In the first line of his voiceover, Henry Hill confesses to having harbored an urge to transgress “as far back as I can remember,” which may as well be all the way back to the Garden.) And of course, it’s supposed to be tempting. Scorsese, a former seminarian and a recovering addict, knows that better than anyone. Goodfellas is a savage satire because it takes aim at a legitimate target, and it’s a weighty moral tale because it has real stakes.

By first mythologizing Henry Hill’s life of crime, and then demythologizing it — showing it break apart in a mean, petty display of disloyalty, brutality and tackiness — Scorsese honors and then questions immigrant aspirations of assimilation and arrival through material achievement, and the classical Hollywood cinema that turned gangsters into populist folk heroes. He first evokes the rush of violence, and of drug use, before showing its grotesque distortions of character; he allows us to swagger along with aggressive, risk-taking males, to join in their camaraderie, before punishing us with depictions of the harm they do to themselves and others, particularly women, and the breakdown of their bonds. Goodfellas is Scorsese’s greatest film because it’s his quintessential statement on excess — why we do it and where it gets us. And Scorsese makes every moment of that journey feel so alive. Come in at any part of Goodfellas while channel-surfing and you’ll watch at least till the end of the scene, and then the next one, and then the next one, because Scorsese and editor Thelma Schoonmaker assemble the film’s 146 minutes into a breakneck preview for itself, in which Ray Liotta’s wired narration and the director’s handsy, active editing-suite presence, all needle-drops and illustrative cutaways, push each other forward. At a time when “MTV style” was transforming mainstream film grammar, chopping up action by a thousand cuts, the equally postclassical Goodfellas is swift, rather than rapid. Its relentless pace and liquid chronology metabolize a narrative of vast scope, and would prove a template for coming information-age epics Casino, Wolf of Wall Street, Irishman and now Killers of the Flower Moon, which cram in even more historical incident — and are, like Goodfellas, harsh yet thrilling tales of the breakdown of friendships, of the failure of love, of American venality driven by the very spiritual incuriosity Scorsese rails against with each searching film. – MA

Thanks for reading InsideHook.

Sign up for our daily newsletter to get more stories just like this.