The French have bestowed Americans with many amazing gifts: The Statue of Liberty; the bikini; Brie cheese.

But maybe the European country’s most incredible gift? The Planet of the Apes franchise.

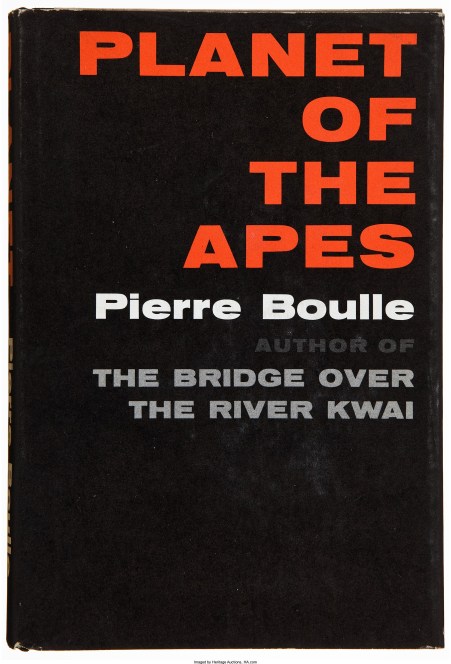

The eponymous book—originally published as La Planète des Singes in 1963 by French novelist Pierre Boulle—provided the basis for the American movie that would reach theaters five years later and go on to become a major box office success. It would also go on to win creative makeup designer John Chambers an Oscar.

RELATED: INSIDE THE PERFORMANCE CAPTURE TECHNOLOGY OF ‘APES’

Though Boulle’s Swiftian plot is a decidedly different beast than the Hollywood sci-fi epic, it’s no less enjoyable and an entirely worthwhile read.

But not everybody enjoyed the book—including the movie version’s marquee actor, Charlton Heston. Starring as Taylor, Heston wrote in the foreword to Planet of the Apes Revisited, “(It didn’t) impress me very much … but the idea did.” (You can’t argue with an Oscar winner’s instincts.) In fact, the author himself even looked down on Apes as one of his more “minor” works, according to Revisited.

The only advocate who seemed to be 100 percent behind adapting the book for the big screen? Producer Arthur P. Jacobs, who made it his life’s goal to bring the novel to life in movie theaters. (Jacobs was living his second Hollywood life by that time, originally a high-powered publicist for stars such as Marilyn Monroe and actor/future president Ronald Reagan, per Revisited.)

“It took years for Jacobs to get that first film off the ground, surprisingly,” Revisited co-author Larry Landsman told RCL. “Sci-fi was a four-letter word at the time, and truthfully, I think (only after) the success of Fantastic Voyage was Fox prompted to finally greenlight Planet.” (The movie studio had even passed on the film after a successful makeup screen test, starring Heston and other actors in the potential cast.)

After the success of the first film, it snowballed into a franchise with Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970), Escape From the Planet of the Apes (1971), Conquest of the Planet of the Apes (1972), and Battle for the Planet of the Apes (1973), carrying the torch. And starting again in 2001, Planet was introduced to a whole new audience, first with Tim Burton’s lukewarm Planet of the Apes, followed by the current prequel trilogy, which has found a much larger audience. (Burton’s version got a 45 percent on Rotten Tomatoes, compared to the latest movie, War for the Planet of the Apes, which landed a 95.)

With War out Friday, RealClearLife wanted to take a look back at the franchise’s roots.

Print vs. Celluloid: Key Differences

Genesis

The original movie version starts off by bringing viewers inside a spaceship, with Heston’s character, Taylor, giving his final report to”Cape Kennedy” before drugging himself to sleep and speeding yet further into the future—the ship’s clock at July 14, 1972 (45 years ago today), while the Earth reaches March 23, 2673. Foreshadowing what will happen later and the ethos of the cinematic era, Taylor asks the men on Earth he believes he’s communicating with, “Does man … still make war against his brother?”

The book, on the other hand, begins with a couple “sailing” through space on a holiday and coming upon a message in a bottle. In it, they find a story written by a French journalist named Ulysse Mérou. He weaves an elaborate tale of how a small team of Frenchman landed on Betelgeuse (which he dubs “Soror”), only to discover that it was inhabited entirely by walking, talking apes. Humans, on the other hand, were treated like the apes of Earth: they were basically caged animals, tested in laboratories, hunted for sport, and kept in zoos.

Sex

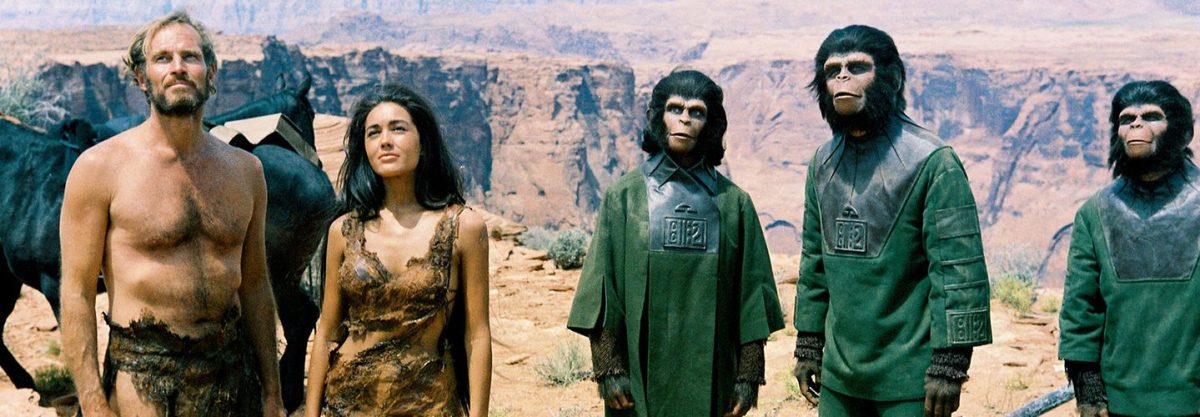

With the original movie reaching theaters in April 1968, just a year after the fabled “Summer of Love” and well into the “hippie” era, it clearly pushed the limits with its onscreen depiction of sex and nakedness. There’s a scene in which Heston’s bare bottom is exposed, and he runs around half-naked for most of the film. The key exception, obviously, is his mute love interest, Nova (played by the gorgeous Linda Harrison), who wears a sort of Flintstones-style getup. And although Taylor does end up kissing the ape-woman Dr. Zira (Kim Hunter), that’s really where the extent of the movie’s eroticism ends.

The book, however, is much more explicit, with Ulysse naked for about three-quarters of the plot and Nova for its entirety. Actual intercourse takes place, too—though the reader only intuits that it happened (Ulysse and Nova do spoon each other a lot). In fact, something that was excised completely from the book for the movie was the fact that Nova had a son by Ulysse named Sirius, who ends up becoming the first “intelligent” human baby born on Soror. (Sirius has yet to show up in any of the many sequels.)

Language

Obviously, the movie was made in English and the apes speak both with American and British accents (Roddy McDowell, who portrays the ape Cornelius, is originally from London). But the book is slightly more complicated. For one, the saga was originally written in French, so the characters are actually technically speaking French translated into English (a British special ops agent from World War II, Alexander Fielding, is responsible for the translation). Also in the book, the apes speak in their own fictional language, which is being translated for the reader first into French and then into English. Ulysse notes that he is able to pick up the ape tongue after awhile, too, and his dialogue with the apes is likely in their own tongue.

Climax

The big climactic ending in the book follows Ulysse escaping back to Earth with Nova and his son smuggled aboard a spaceship. They land at Paris’ Orly airport, seeing the Eiffel Tower in the distance. But after disembarking they’re met by—you guessed it—a gorilla. And that couple who’ve been whizzing throughout space reading Ulysse’s story from his message in the bottle? They’re apes as well. “That was one of the challenges Arthur Jacobs had in terms of translating this wonderful book into a screenplay that they could afford to make,” explains Landsman. The original script had had the Ulysse character finding the modern ape city. “But it would’ve been hard for the audience to understand why he wouldn’t see that it was Earth,” he continues. As perfect a book ending as it was, it didn’t work for the big screen. Fortunately, the version ginned up for the movie became iconic in its own right.

The film’s climax is one of the most iconic “twist” endings in cinematic history. As Taylor and Nova ride off into the sunset along the coast on a horse, a large, tangled-metal structure comes into view. Taylor rides on, and out of the lefthand side of the screen comes a pointed piece of metal.

He dismounts, looking up at the structure, exclaiming, “Oh my G-d! I’m back … I’m home. All the time was …” He drops to his knees and continues, “They finally, really did it.” Then screams, “YOU MANIACS! YOU BLEW IT UP! GODDAMN YOU! GODDAMN YOU ALL TO HELL!”

And that’s when the camera pulls away, revealing a half-buried Statue of Liberty—the remnants of the human society that Taylor had left behind on Earth. It’s not only a bold twist, but also a not-so-subtle hat-tip to the book’s French roots. And, according to Revisited, most likely an O. Henry–style ending from the genius mind of co-screenwriter Rod Serling (he of Twilight Zone fame). Watch how the scene was filmed below:

Other Details to Go Ape Over

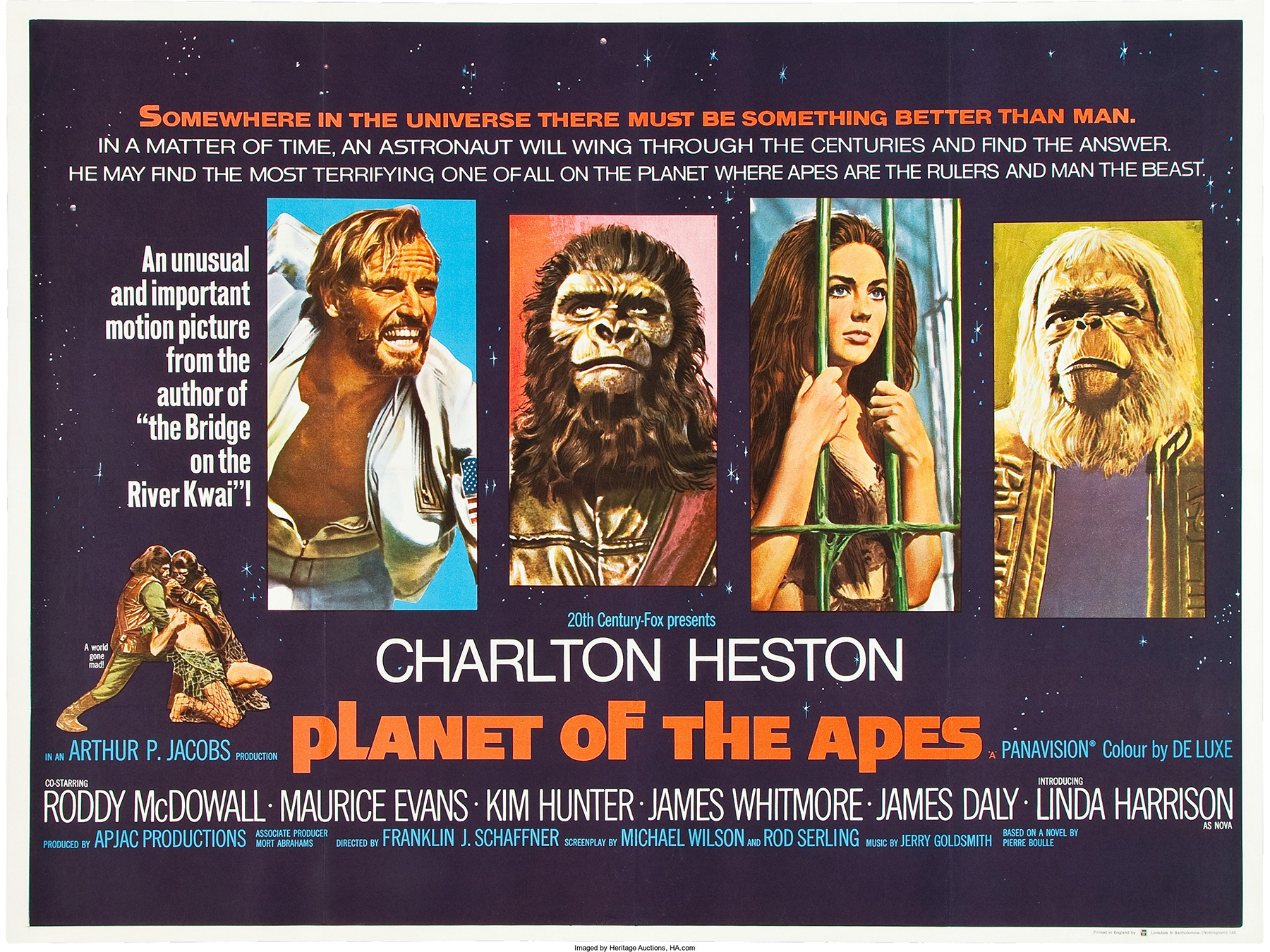

The Casting – Enough can’t be said about the ensemble cast, headlined by Heston and Harrison, which also includes Maurice Evans as Dr. Zaius (Hutch in Rosemary’s Baby), James Whitmore as President of the Assembly (Brooks in The Shawshank Redemption), and even bit-parters like Norman Burton (Felix Leiter in Diamonds Are Forever).

Soundtrack – Master film composer Jerry Goldsmith—whose wide-spanning résumé includes scores for Chinatown, Alien, and L.A. Confidential—took a highly dissonant, atonal, percussive route for the Apes‘ score (listen to the main title here). It’s a tough listen; at times, it sounds like musical gibberish. But added to the film, it’s right up there with Jaws and Star Wars in how it’s able to help set the scene.

Memorabilia – As far as merchandising is concerned, Planet of the Apes spawned its own cottage industry—but not until 1973-74, notes Christopher Sausville in his epic Planet of the Apes Collectibles: Unauthorized Guide with Trivia & Values.

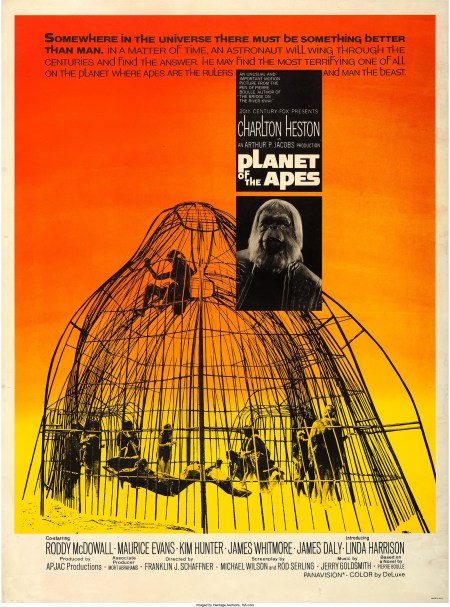

And while the toys, comic books, Halloween masks, candy boxes, frisbees, models, puzzle, T-shirts, and collectible cars are a lot of fun to buy and look at, the real money is in the original posters and film props. Take this set of door panel posters for example (as is noted by their name, they would’ve appeared on the movie theater’s doors). They sold in a Heritage auction back in 2008 for $7,170. Or this poster that sold for $1,195 just last year (see above). Not to mention this screen-worn gorilla uniform that went for a highly reasonable $836.50 back in 2005.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.