Hayao Miyazaki’s career-spanning mission to unfuck the world will not be a success. Eventually, he’s going to die — probably on the sooner side, having passed his 82nd birthday earlier this year — with the lofty ideals set forth in his body of work left unfulfilled. Like every humanist to come before him, he must accept that realizing the unattainable dream of an end to war, a harmonized state of nature and a kinder future will fall to the next generation. Studio Ghibli, the humble anime empire that he’s built over nearly four decades of excellence, shall take on a new overseer, its continuation or crumbling beyond the control of its cofounder. His canon can and should sustain appreciation and study with the longevity of Sophocles’ writings, but the planet will continue spinning without him all the same.

The Boy and the Heron, a farewell feature (unless it’s not, an option always left on the table by the prolific fake-retirer) unmistakable in its satisfying yet heart-pulverizing finality, represents the master’s effort to make his peace with the impossibility of peace in his lifetime. Like a rock allowing a stream to freely flow around it, his cinema centers itself on a meditative serenity unperturbed by the noisy, hectic bustle of urbanization kept far from his idyllic pockets of the great outdoors. In his parting statement, a pronounced accedence not to be mistaken for resignation puts a comforting yet deeply saddening cap on an oeuvre of incalculable influence and unparalleled inspiration. More than coming to grips with the eternal truism that we can’t take it with us, he embraces impermanence and locates a melancholic poetry in the certainty that nothing lasts forever. By the final shot that shatters and heals in equal measure, we don’t even want it to. All the endings and beginnings blend together into a single beautiful continuum of continuation.

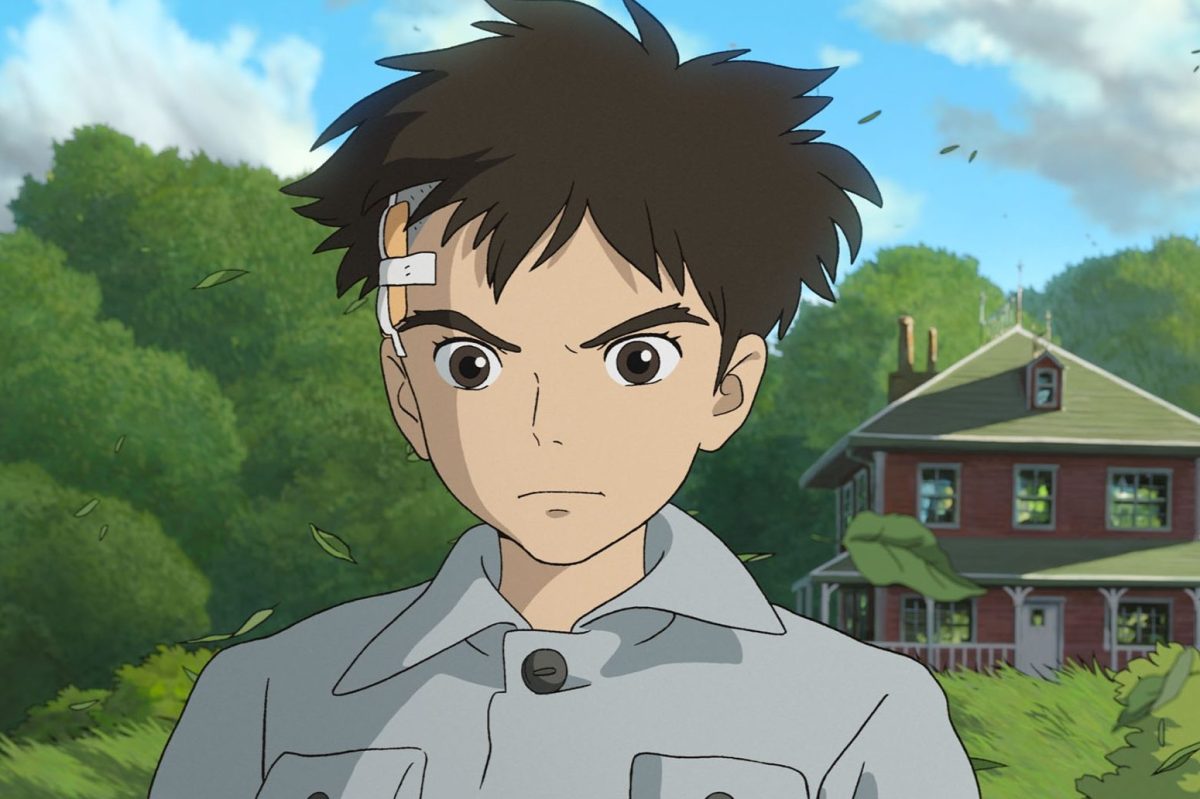

Maybe this thinking about the circularity of time compelled Miyazaki to draw on his most popularly beloved title in crafting a goodbye, as if saving a weathered cover of his greatest hit for the encore. He borrows his own plot contours and character templates from Spirited Away, which also set its fable in motion with a kid’s reluctant move to an unfamiliar suburb. After Mom perishes in a firebombing during World War II, moody Mahito (Soma Santoki), his dad Shoichi (Takuya Kimura) and his aunt-turned-stepmom Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura) evacuate to the countryside to start over in safety. Wrestling with a grief far beyond his emotional maturity level and harangued by bullies at school, Mahito seeks solace in a hidden dimension at the beckoning of an impish spirit who hangs out inside — and occasionally protrudes from the mouth of — a grey heron. Operating under The Wizard of Oz’s garbled associative logic, this equally ravishing dreamscape reconstitutes Mahito’s waking hopes and anxieties as a symbolist quest to let his mother go.

Through a journey that rivals Miyazaki’s finest on visual comedy and sheer gorgeousness, Mahito forms a traveling party with familiar types: a clever witch, an extraordinary girl with powers beyond her comprehension, the obligatory gaggle of chittering little chibis. In a nod to the imperialist conflict raging back in Mahito’s reality, an army of man-sized carnivorous parakeets under the command of a megalomaniacal king menace Mahito despite the inherent hilarity in every movement they make. The fantastic odyssey through oneiric door-to-nowhere abstraction ultimately leads to a warlock responsible for maintaining the fragile balance of this universe, embodied by a stack of different-shaped blocks he prevents from toppling. A legible stand-in for Miyazaki, he waxes rhapsodical on his need to find a pure-hearted successor capable of taking up his sacred duty, and explains the source of his authority as a rock chiseled with the whorls of a gigantic fingerprint. The implied fear that he and he alone possesses the inbred ability to bear an Atlas-sized burden clarifies the subtext of some dialogue about his bloodline; completists will recognize the comment on his well-documented ambivalent relationship to his actual son, the demonstrably inferior computer-animator Goro.

Never shy about speaking his mind, Miyazaki has freely expressed his disgust with the ecological ruin and rapaciousness of capitalism, both of which he’s complicit in as a workaholic who’s surrendered his characters for merch sales and a theme park. He doesn’t so much attempt to allay his own guilt in these pointed metaphors as let it subsume him, self-destructing until only his trust in tomorrow remains. Our loved ones die; we let new loved ones into our lives. Every fall, trees lose their leaves, and come spring, they’re reborn. Unending cycles of annihilation and creation will continue far past any of our memories, an insignificance that one can choose to take either as a crushing existential weight or a slant on reassurance. We’re just passing through, and the most any of us can do — the way to traverse the path through being, a concept rephrased by the liberally adapted 1937 source novel’s title of How Do You Live? — is to find a steward worthy of taking our place. Barring that, if the designated heirs decide they’d rather forge their own way of self-determination, we can solemnly bow our heads and return to the earth from whence we came.

If You Haven’t Seen “The Adults” Yet, You’re Missing Michael Cera’s Best Work

The actor delivers a career-best performance in the independent sibling dramedyThe sagelike conciliation with death has the side effect of drawing out the preciousness of a singular vision, reminding us that we may very well be seeing the final reserve of a finite artistic commodity. A name often misapplied as synonymous with the varied output of Ghibli or the whole of anime itself, Miyazaki reasserts the bittersweet fact that no one can do what he does as text, and simultaneously proves it via some of his most rapturous snatches of pastoral grace. Slats of light filter through air with a tangible quality, dappled between arcing tree branches; water moves with a gooey viscosity that somehow captures wetness more faithfully than an accurate rendering would; the customary food-prep interlude tantalizes with delicacies too perfect to be real. The highest virtue of animation lies in its stylistic freedom to make anything look like anything, and Miyazaki graciously permits public entry to the cozy, soothing realm where he serves as sole gatekeeper.

Adult viewers would easily forget that this is all for children, or at least designed to qualify for their enjoyment, if not for the simplicity with which Miyazaki manifests complex, mature emotions. It’s Mahito’s story, after all, and it guides him to Spirited Away’s moral emphasizing the importance of individual, questioning thought over the obedience lesser kiddie fare would sell to suggestible girls and boys. At any age, it behooves a person to make their own decisions and reckon with their consequences, an internal negotiation that grows more difficult as a life accumulates mistakes. Miyazaki conducts this personal inventory with unsparing judgement and qualified forgiveness, buoyed by his enduring love for the forest and its peculiar inhabitants. For the last time — probably — he performs the miracle of pairing a child’s unsullied, wide-eyed innocence with the wizened wisdom of the aged. In doing so, a man keenly aware of his proximity of mortality becomes ageless.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.