Without fail, Wisconsin remains one of the drunkest places in America. The beer-and-brandy soaked state consistently leads or places among the top contenders in America’s Drunkest States round-ups, and this past January, the Badger State clocked in with 12 of the top 20 entries of the Nation’s Drunkest Cities as compiled by 24/7 Wall Street. Overconsumption of alcohol is a serious matter and can be problematic on many fronts, and most states might try to quickly bury such headlines from the daily news cycle, but Wisconsinites wear this black eye like a badge of honor after a bar fight.

“Drinking is part of the state identity. In a weird way they’re perversely proud of it. It’s a part of life,” says Milwaukee native Robert Simonson, an acclaimed drinks writer and author who now lives in Brooklyn but makes it back to his home state three to five times a year. (He also famously dons a glittery green-and-gold Green Bay Packers Santa hat at his annual Christmas party as he mixes up Tom & Jerry’s for guests.)

Even with the number of influential bartenders hailing from Wisconsin, or those who have attended college there — like Jim Meehan, who opened the influential New York cocktail den PDT, or restaurateur Gabe Stulman, whose New York City-based Happy Cooking Hospitality group includes beloved West Village spots Jeffrey’s Grocery, Joseph Leonard and Fairfax — Wisconsin drinking quirks and customs rarely migrate out of state. “Wisconsin didn’t teach the world to drink, but we have ten times as many drinking traditions as any other given place, except perhaps San Francisco or New Orleans. We held on to them. We’re not swayed by fashion,” says Simonson. “Wisconsin taught Wisconsin how to drink, and they don’t give a damn how anybody else drinks.”

Bringing your kids into a bar is typically frowned upon, yet running around a Wisconsin tavern for an hour or two while your parents posted up at the bar is a familiar memory to many Wisconsinites. “I grew up as a kid where you go into the bar with your parents and they go in have a drink and play cribbage while the kids are under the pool table picking up dimes, running around shrieking, and having root beers and Shirley Temples and cream sodas,” recalls Toby Cecchini, who grew up in Madison and has been tending bar for 33 years. “It’s just part of life. Of course you bring your kids to the bar. You just grow up there among the sticky carpets and mounted muskies on the wall. That’s just a whole culture.”

Cecchini is co-owner of The Long Island Bar, one of the most beloved neighborhood bars in Brooklyn. From the pink and green neon sign to the well-worn red-leather booths, it’s one of those timeless bars that instantly evokes a universal pang of nostalgia for your favorite hometown tavern, no matter where you grew up. There’s a Wisconsin Tavern League sticker on the door and some sly winks to Cecchini’s home state, such as the vintage Jim Beam decanters in the form of a Green Bay Packer and a muskie (the state fish) on display next to a tray of bitters bottles by the cash register, and, of course, the Lombardi Room in the back of the bar. The biggest tribute, though, are the Long Island Bar’s fried cheese curds. They ship the curds in from Wisconsin and when they come out of the fryer they’re adorned with jagged little stalagmites of fried batter just waiting to be swept through the saucer of housemade French onion dip that accompanies them. They may be fighting words, but many natives admit they’re better than most fried curds you’ll encounter back in Wisconsin.

Wisconsin’s reputation for beer and brandy consumption was grounded with the mid-1800s immigration waves of Germans, as well as Norwegians, Poles and Irish who brought with them their northern European drinking traditions. The extreme climate of Wisconsin, with punishingly cold winters and scorching summers, factored into the constitution and character of its citizens, and the solid foundation of a strong work-ethic was fostered by the many families who took to farming. The wave of German immigrants eager to maintain their own cultural traditions were responsible for the legacy of breweries across the state and the reputation of Milwaukee as “the beer capital of the world.” Beer was plentiful and inexpensive, which partnered well with the practiced frugality of most Wisconsinites. Many of these heritage breweries have since closed or been consolidated into bigger brands over the years, but the beer culture remains a key component of the state’s identity.

“You know that joke where people are cutting back and they’ll say, Oh, I’m not drinking this month, I’m only drinking beer? That’s how Wisconsinites look at beer,” says Simonson. “It’s very close to water. You’re having a Schlitz or a Pabst or a Miller High Life. You’re not doing that much damage.” The New Glarus Brewing Company stands out among the modern craft breweries as they only sell their beer within the state of Wisconsin (one of their most popular beers is a naturally cloudy farmhouse ale called Spotted Cow). This elusive unattainability makes beer geeks and Wisconsin ex-pats want it even more and some go as far as to bootleg cases of it, Smokey and the Bandit style, across state lines. But buyer beware. In 2009, the Upper East Side bar Mad River, a gameday gathering spot for University of Wisconsin alumni, was busted and heavily fined by the New York State Liquor Authority for buying and selling unlicensed New Glarus.

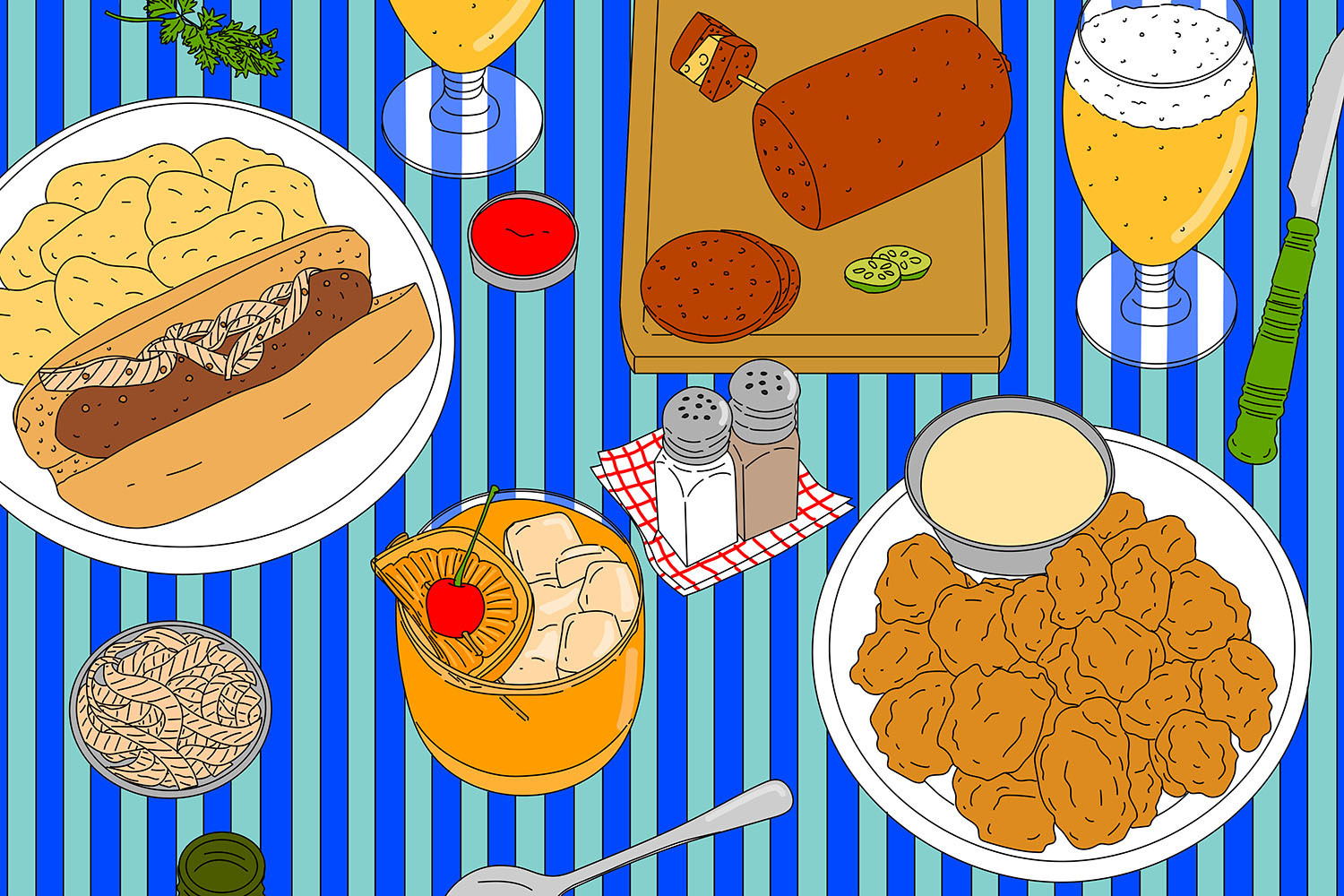

Out of loyalty, some Wisconsin restaurants will even advertise what local beer they use in their fish fry batter, and parking lot debates ensue while tailgating on the qualities of the particular beer used to soak and boil your bratwurst before finishing them off on the grill. But one truly unique Wisconsin method of beer consumption is the snit, a beer chaser served in a short glass alongside a Bloody Mary. This ritual started sometime in the 1980s and while Wisconsin doesn’t lay claim to inventing the Bloody Mary, they’ve gone all in when it comes to over-the-top garnishes that take the form of towering skewers speared with cheese curds, chunks of summer sausage, pickled peppers and even fried chicken legs, among other savory accompaniments (yet another nod to the Wisconsinite’s pursuit of a good deal).

Wisconsin native Brian Bartels, a longtime bartender and author of The Bloody Mary and the recently published The United States of Cocktails, sees the snit as a shining example of what he calls “tandem drinking,” pairing up two alcoholic beverages in one serve, like a boilermaker. “This celebration of beer at brunch, or any time of the day, allows us to appreciate what we have with an extra little cherry on the sundae,” he says. “It’s a culture and lifestyle that more people need to embrace.”

Bartels first met Jim Meehan when Meehan was the doorman at Paul’s Club, a popular college bar in Madison. Bartels later became a bartender there himself and in an All Roads Lead to Paul’s Club fashion, he crossed paths with Gabe Stulman there as well (as the story goes, Stulman once tried to walk out the door with one of their barstools during a raging snowstorm; he didn’t make it that far and all was forgiven). Bartels looks back on that time grateful for the older bartender who trained both he and Meehan while they worked there. “It was a great place to appreciate that position but to also flourish in a way that enabled us to really hit our stride at a young age when a lot of bartenders probably weren’t taking it that seriously, ” recalls Bartels. “It was a place that enabled us to use our personalities. If you were behind the bar you were running the show.”

In less than a year’s time Meehan, Bartels and Stulman all moved to New York and Bartels spent 15 years in Manhattan working behind bars, 10 of those as a managing partner in Stulman’s restaurant group. He recently moved back to Madison to open the Settle Down Tavern with two of his best friends, Sam Parker and Ryan Huber. Beyond the stress of opening a new business in the middle of a worldwide pandemic, Bartels found that he had to go through a bit of basic training behind the bar to meet the demands of Wisconsin drinkers. “I can tell you from what I’ve forgotten being in New York for 15 years that I’ve had to relearn in the last two months,” says Bartels with a laugh. “You can’t make drinks fast enough. People drink here at a pace and velocity that is unparalleled. It’s a state that very much goes hard. The rate at which, and the volume at which, people drink in Wisconsin — and do it with effortless grace — is impressive.” And yes, the Settle Down Tavern does have a Friday fish fry.

The unofficial state drink of Wisconsin is, hands down, the brandy Old-Fashioned. “Only outside of Wisconsin do you call it a brandy Old-Fashioned. It’s just an Old-Fashioned,” says Cecchini who then slips into a pitch-perfect Upper Midwest accent of a Wisconsin bartender (if you’ve seen Fargo, you’re familiar with it). “Some weirdo came in here looking for whiskey in his Old-Fashioned. Probably a FIB. I told him to go to hell,” he says, dropping the local slang for a “Fucking Illinois Bastard.”

To make a brandy Old-Fashioned you start by adding a sugar cube, orange slice and neon red maraschino cherry to a rocks glass followed by a few healthy dashes of Angostura bitters (There’s a reason they sell a ton of Angostura in Wisconsin. Visitors to Nelsen’s Hall Bitters Pub, the oldest legally operated tavern located on the isolated and hard-to-access Washington Island, who knock back a full shot of Angostura bitters are allowed to add their name to a ledger and leave with an official Bitters Card.) and a splash of soda water before muddling together. Instead of the traditional rye or bourbon, a heavy two-ounce pour (Cecchini: “Two ounces? Are we making this for children? Let’s call it a ‘glug.’”) of inexpensive domestic brandy (typically Korbel from California, which Simonson notes was first introduced at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago and then purportedly marketed exclusively to Wisconsin in the 1930s after Prohibition) is free-poured in the glass followed by ice. And then things get interesting as each drink is personalized with the option of having your brandy Old-Fashioned “sweet” (topped with a splash of 7-Up or Sprite), “sour” (topped with a splash of Squirt or sour mix), or “press” (topped with a 50/50 combination of 7-Up/Sprite and soda water). Give it a stir and garnish with a fresh orange slice and cherry and immediately order another one.

“The brandy Old-Fashioned is a paradox because it’s a very populist drink,” says Simonson. “It’s for the people, and yet it’s complicated. Even though someone who’s not from Wisconsin might have one and say what’s the big deal, it’s not really a great drink. But with all those variables it’s actually difficult to get to that end result. But to a Wisconsinite, this is a great drink and they know a good one from a bad one. They’re like Sazeracs in New Orleans. I’ve tried many different Sazeracs from many different places and they’re all different, yet they’re all in that Sazerac family. It’s the same in a Wisconsin bar. Every brandy Old-Fashioned is different.”

Compared to the austere, spirit-forward version of the Old-Fashioned now served at most cocktail bars, the brandy Old-Fashioned can be a bit slight on impact. The combination of domestic brandy, sweet muddled fruit, mixers from a soda gun, and crappy bar ice which quickly dilutes the drink leads to something that Simonson calls “more constant than serious.” But by the second or third one they become quite sessionable. “If you’re drinking for eight hours in Wisconsin you can make anything sessionable,” adds Cecchini, who’s gained an admittedly “weird, grudging respect” for the brandy Old-Fashioned. “It’s actually super delicious. Obviously it’s made out of silly things and if you try to gussy it up you lose the entire thing,” he says. And there’s no point in trying to order one outside of Wisconsin; it just doesn’t translate beyond the state borders. Cecchini hasn’t trained his staff at The Long Island Bar to properly make them but he keeps a bottle of Korbel brandy behind the bar and can cobble one together for the right occasion, though he admits he’d have to run to the bodega across the street for the 7-Up and Squirt.

Brandy Old-Fashioneds are also ingrained in the history and tradition of Wisconsin’s supper clubs, restaurants that populate Upper Midwestern states (while some are dying out there are over 250 in Wisconsin) which serve as a community hub dressed up as an old-school steakhouse. Some are so popular that people will drive for miles from out of state to visit; for locals, dining out at one can be a regular event or saved for a special occasion (the older generation might even throw on a jacket and tie), but it’s generally a family affair (unless you can afford a babysitter) and it’s made for lingering and catching up with friends and fellow diners over the course of hours. Some start at the bar with a Martini or a Stinger but typically you’re drinking brandy Old-Fashioneds. You have a couple of those while nibbling at the gratis trays of pickled vegetables and sideboards of Ritz crackers and cheese dip while you wait for your table. There will be steaks and seafood and fried fish (typically a fresh-water lake fish like walleye, or perch if you’re lucky) and you select your soup, salad, starches and sides to round out your meal. It can be expensive, but the plates of food are enormous, and the casual aesthetics allow you to linger in comfort.

The sweet finish at many supper clubs comes in the form of yet another quirky Wisconsin concoction, the over-the-top, boozy, blended ice cream drink — what Bartels calls the “feather in the cap” to the supper-club experience. Most stick with the Grasshopper, Pink Squirrel or Brandy Alexander, which Bartels dubs “the holy trifecta of the Wisconsin cocktail canon.” Simonson notes the ice cream drinks are a confluence of many Wisconsin factors. “It’s the whole state in a glass,” he says, as two different electric blender innovators were from the area, it’s a dairy state with tons of great ice cream readily available, and most Wisconsinites have a tremendous sweet tooth. “And again, there’s that thing about wanting to get the most for your money,” he says. “An ice cream drink is a meal. You order one of those and you likely won’t be able to finish it and yet still come away with a light buzz.”

It’s starting to make sense now when you realize that some of the nicest, most interesting people you know are from Wisconsin. And like many, no matter where you’re from, there’s an undeniable sense of comfort returning to your home state, whether for a visit or re-establishing roots. But Wisconsin seems to have an allure to many people who have actually never been there. “We live in New York and there’s a lot of culture vultures and trend-suckers and that can get very weary after a time, chasing after the next new thing. There are very few new things in Wisconsin,” Simonson muses, taking one last sip of his beer. “It’s like coming back to an embrace. We know what you want. Here’s your brandy Old-Fashioned. Here’s your fish fry. You OK? You need another relish tray? That’s nice. It’s like going home to the family.”

Join America's Fastest Growing Spirits Newsletter THE SPILL. Unlock all the reviews, recipes and revelry — and get 15% off award-winning La Tierra de Acre Mezcal.