Karim Rashid is currently working on his most personal project yet: his own home.

“It’s my COVID project,” explains the superstar industrial designer, recipient of the American Prize for Design and, as he once was dubbed, the “Prince of Plastic.” “I needed an escape from Midtown New York but there’s been such an exodus out of New York I couldn’t find anything anywhere. Or there was a bidding war on every house in Jersey. So I thought, hang on, for years I’ve dreamed of building my own house, so I’m doing it. And now I understand how complicated that is. My clients are much more relaxed about their projects than I am about this.”

The high-ceilinged, outsize-windowed, flat-roofed modernist design — well, you didn’t expect mock Tudor, did you? — is due for completion in January. That’s if Rashid can stop second-guessing every decision he makes.

“When I look back on projects I feel I’ve over-designed, that’s what I did then. Now I’m doing it with my house. It’s torture,” sighs the London-born, Canadian-raised, New York-based, half-Egyptian, half-British designer.

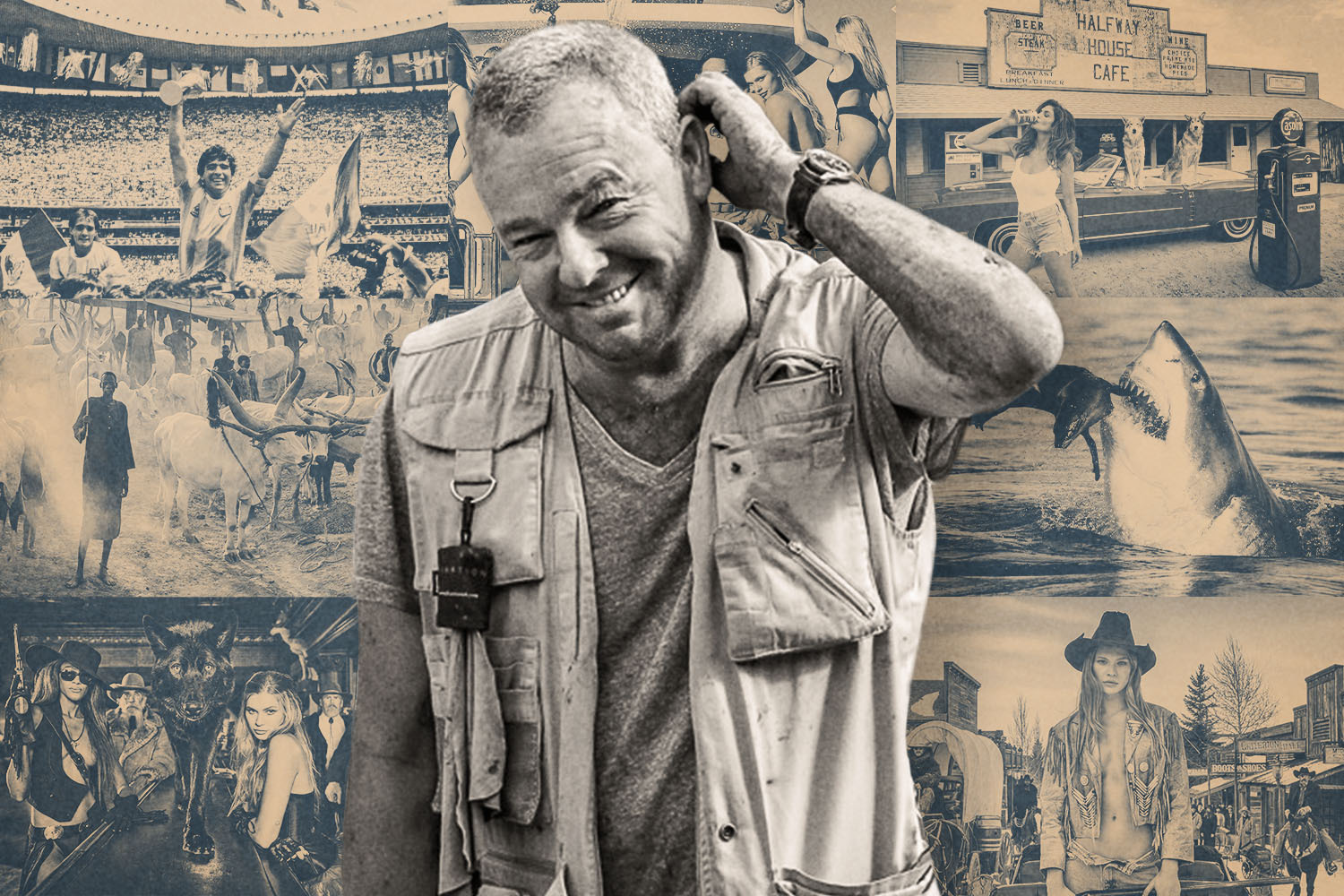

Certainly the no-choice-downtime of the pandemic has encouraged Rashid — whose projects have included everything from hotels, restaurants and shops to power tools, perfume bottles, chairs and toys — to get going on a number of things he’s had on the back-burner.

He is, he says, “a big wine drinker — to the point where I think I really have to stop drinking wine,” so this September he’s launching his own. “It’s called Karim,” laughs Rashid, knowing that this may be the one time his imagination has let him down. It’s a low-sulphite Italian red and white, the bottle for which is, he promises, “very cool.” And he’s even opening an art gallery-cum-coffee shop in NYC.

“It’s all super contemporary, with a barista behind a floating pink neon counter, one machine, three cup sizes, plus all this art by all the great artists I know from around the world who have never got to show in New York,” he enthuses. Don’t ask for marshmallows or whipped cream, though. Rashid may be known for his love of candy colors, but he’s strictly Bauhaus when it comes to his coffee.

It’s precisely that Rashid is often stereotyped by his love of pop color and curvaceous forms that the content of his designs is too often overlooked. In economically straitened times, he thinks his public image might even work against him.

“I think I lose work out of the fear of what I represent on the surface, not least because times have changed a lot in the design world — everyone is so worried about the bottom line and so fewer brands want to be provocative,” he explains. “But I’ve done a lot of hardcore industrial design and don’t see myself as just a stylist: here’s an object, make it soft, make it pink, and so on. You have to be so critical of yourself when you’re designing to be original, but often originality and relevance comes from focusing on functionality first. I’m actually so practical it annoys me. But if something is driven by functionality it will inevitably have greater longevity because it’s driven by human experience.”

All the same, Rashid has, he admits with great candor, found his work less and less in demand over recent years. That’s especially the case in the U.S., where, for reasons inexplicable, and contrary to the rest of the planet, he’s never really caught on, though he is presently working on a building in Chicago and a private residence in California. In part, he suspects, it’s a product of his age. He’s now in his 60s. The last 20 years of the careers of design gods Verner Panton and Oscar Niemeyer were, he notes, likewise bare ones. Fellow designers of his pedigree and caliber, friends of his, are seeing the same, he suggests, in part out of their refusal to compromise.

“Designers border too much on the artistic side and have too much integrity and aren’t prepared to compromise. Some just won’t take the project and end up doing a lot of sculptures. I’m one who has compromised a lot, understanding that if you don’t, you don’t get the project,” explains Rashid, who, with some 3,000 designs under his belt, is likely the most prolific industrial designer of the last 30 years.

“It’s not about you and your ego, drawing something and saying, ‘Make this!’ That’s the way to not get something made. Why did a company come to you in the first place? They want to sell more things, so you have to design something that makes sense for them,” he adds. “You have to take off the artist’s hat to get things made. And at least then you can take satisfaction from having improved what’s available in that category, be that a waste can or a soap dish. You’ve added a little bit of something better. It’s good enough — 70% — if not perfect. It’s a tough profession.”

It’s also a profession, he says, that only looks set to get tougher. Rashid is comfortable and says he is long past the time “when I was worried about acceptance, winning accolades and prizes [he has some 300 to his name], success financially, socially — but that’s all about ego too.” But he does worry about how the creative classes fit into today’s world, especially in how their expertise is regarded.

“It’s not as though my workload is going down — I get a lot of offers. The thing is that many people now don’t want to pay,” Rashid laments. “There’s something happening to the profession. I think it’s because design awareness has driven a lot of young people to go into the profession. It’s absurd the number of designers and architects graduating now. With saturation, the industry has become so competitive you have people willing to work for next to nothing. It goes back to the historic notion of exploiting artists. But we’re not artists — we produce commercial goods, we contribute to capitalism. But because we’re creative there’s the assumption we can just knock out an idea, or that you’d be doing the work anyway and so don’t need to be paid.”

That includes even a name as big as Karim Rashid’s, whose very attachment to a project will generate sales. “But in design you get to the top, the industry sees you as good for the PR machine for a while,” he says, “and then it spits you out.”

Rashid says he was recently approached to design a hotel in Rome and was offered a quarter of what he was paid to design another hotel for the same company a decade ago. Then they halved that amount. Finally, they pulled the offer because they’d found a designer in Rome to do it for a pittance. Rashid sees the same collapse in other creative professions. Interior design has been killed by Instagram. Graphic design? “Well,” he says, “there are systems now that will knock you out a company logo for $50.” Architecture? Only surviving because building regulations demand their involvement.

“But that doesn’t mean you have to work with a creative architect,” says Rashid. “With rapid prototyping of buildings it’s just a matter of time for that profession too.”

On the plus side, he stresses, design has been democratized. When he started out in his industry, “everything was so awful in its design,” he says. “Now everything, down to your thermostat dial, is beautiful. The improvement in the physical landscape is fantastic — all these products coming out of China that are entirely anonymous. Mass manufacturing companies — Nike, IKEA — have really pushed design too.” Good design, he suggests, should drive to higher standards and command more respect. After all, he says, “design shapes our social experience, makes our lives better or worse. Bad design just becomes an obstacle to everyday life.”

At least with his new home, his wine and his very exacting Americano, Karim Rashid will ensure that it’s good design all the way, with only compromises of his own making.

“Obviously I’m diversifying a bit,” he chuckles. “But maybe now more than ever it’s important to find something you’re passionate about.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.