The murky future of children tends to brings out impassioned takes from both parents and teachers. Understandably so, considering: A) toddlers can’t contextualize or articulate their setbacks on their own, and B) caretakers generally feel that they know the issue better than anyone else.

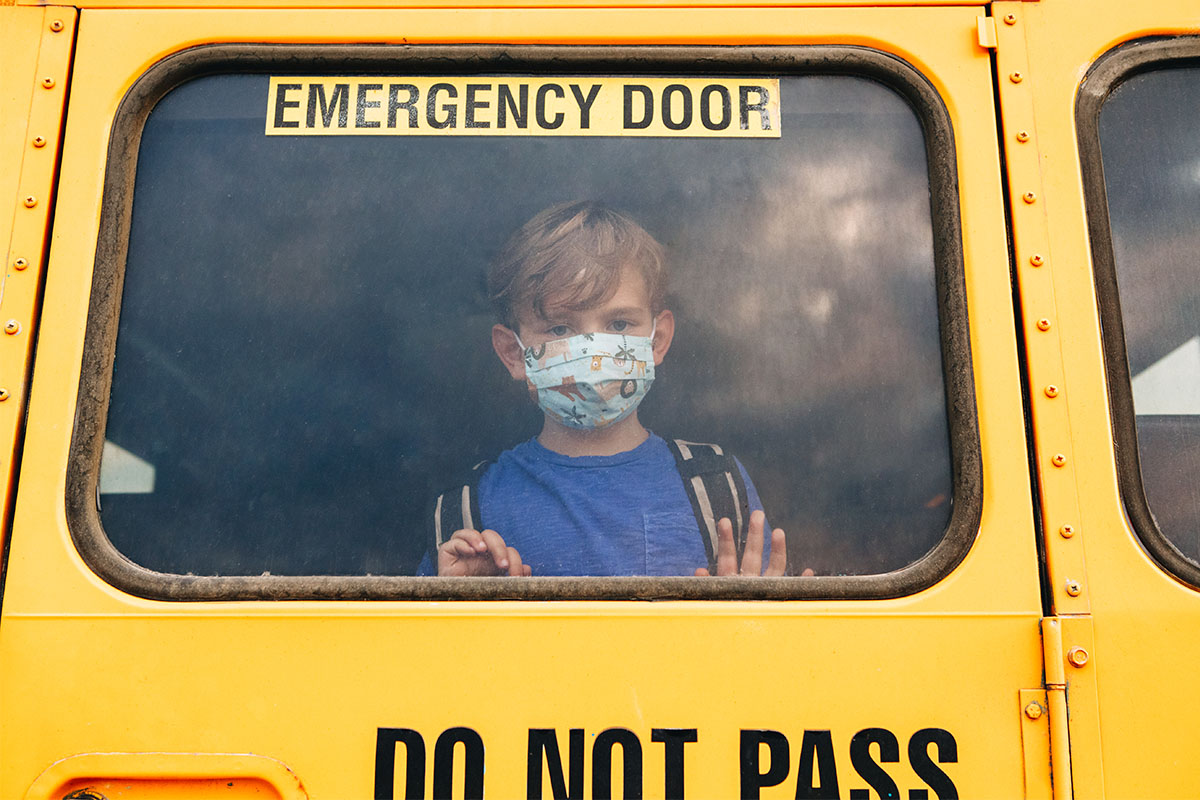

Over the last two years, as that future has been upended by the pandemic, and kids have been forced to weather remote learning, mask-wearing, canceled playdates and the closure of camps and clubs, caretakers are more concerned than ever. The overriding take? Our kids are falling behind. This worry reached a fever pitch in the debate over school closures; at one point 90% of parents reported fears that their children would “fall behind academically due to coronavirus-related school closures,” which ranked higher than any other financial or socioemotional concern in their lives.

The thing about that, though — American children have been falling behind. For years. Before the pandemic even arrived, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OCED) had already completed a report on early learning and well-being in young children across three countries: the United States, England and Estonia. American tots ranked far behind the English and Estonians, in virtually every metric.

Too often, American caretakers imagine this issue as something that starts (and therefore must be solved) at school. Which is to say, American kids begin losing the race at age four or five, in the classroom. But the latest work from childhood-learning researchers — most of which is outlined in a fantastic essay in Scientific American — indicates that the youngest among us start falling behind years before they ever pack a backpack. Their disadvantages start right at birth, representing the structural and social failures of a country that does less for its children than any developed nation on the planet.

These failures (among them a refusal to guarantee parental leave, scattered access to quality child care and a rollback of child allowances and tax credits) have created an uncomfortable relationship between poverty and poor neurodevelopment. In other words: too many young American brains aren’t maturing correctly. They’re showing smaller surface area and more low-frequency waves, each illustrative of brains that have been trained to react to tough times, instead of open themselves to language and memory.

The simple fact is that parents need to be with their kids — and that time should be as low-stress as possible. As a pair of authors wrote in Scientific American: “Two decades of child development research tell us that small kids need two things above all else to get off to the best possible start: nurturing interaction with caregivers and protection from toxic stress…studies show that environments and relationships we know benefit development are also associated with higher levels of activation and connectivity in parts of the brain that underpin language and cognitive development.”

Miraculous things happen when caretakers sit down with children; conversation turn-taking, in which the parent offers up a diverse quantity and quality of words, pays dividends that will benefit the child into adolescence. When children feel seen and heard — it doesn’t matter how little sense the may be making — it encourages curiosity, maturity and creativity.

It’s a simple formula, but we live at a time where setting aside real, honest time with children is not incentivized by employers or the government. In a twisted, confusing way, parental care has become associated with vacation and leisure, an expense that often can’t be readily justified.

This is the future of American children, until we figure out common-sense reform for child care. Corporations and Congress can shout opinions all they like, but this isn’t a subjective debate; it’s brain science. When parents can’t see their kids for more than an hour or two a day, when daycare means a kid sitting in front of a TV, and when the lack of tax credits means kids grow up in homes rife with stress, where food is scarce, or the air conditioner is broken, we can’t be surprised that American kids enter schools distracted, combative, or unequipped to learn. The pandemic has taken so much, but at the very least, it’s illuminated an alarming trend that was already there.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.