Fitness wearables with sleep-tracking software emphasize the importance of sleeping through the night.

They catalogue “disturbances” (all the times you woke up, whether you remember them or not) and prize a night’s sleep that goes through all four stages (three non-rapid eye movement cycles, then the rapid eye movement cycle) three to four times, over the course of a consistent seven-to-nine hours in bed.

After all, this sort of deep, steady sleep is where all the magic happens. Your brain sorts and processes all the things you saw and learned that day; the pituitary gland floods the body with growth hormone, which helps your muscles repair and strengthen; your immune system ships small proteins around the body, meant to fight inflammation and infection; and the sympathetic nervous system finally gets a chance to take a lap and cool down, as blood pressure drops and cortisol release decreases.

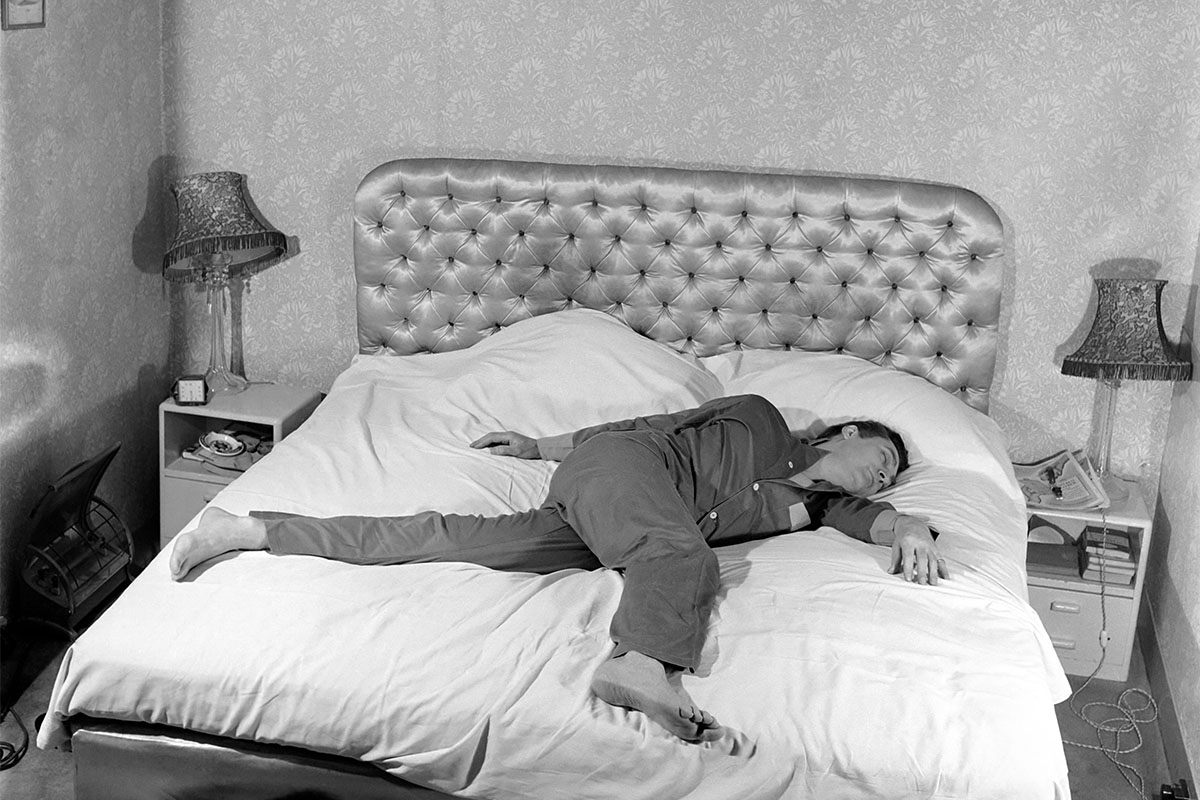

Challenging this wisdom, though, and taking advantage of the flexibility of the work-from-home era, are “segment sleepers.” Instead of sleeping straight through the night, segment sleepers may, for instance, sleep from 10 p.m. to 2 a.m., then read, meditate, or even stand outside for a couple hours or so, then sleep from 4 a.m. to 7 a.m. In the end, they’re technically reaching the minimum recommended amount of sleep a night (seven hours), they’re just doing it on their terms.

According to a profile by The New York Times, which featured quotes from a variety of historians who study human behavior, this sort of on-again-off-again sleeping pattern was customary for multiple cultures for thousands of years. Farmers didn’t exactly have commutes in the Middle Ages. They made their own hours, shaping them around the natural rhythms of day and night, and went to bed a lot earlier than we’re used to. They’d wake up naturally in the middle of the night, and putter around for an hour or two, before heading to rest again before it was time to get up and start working.

What they’d do with those hours depended on the person. Medieval monks would use the time after “the fyrste slepe” to say prayers, while many couples found it a perfect time to have sex. A 16th-century French physician claimed that partners “have more enjoyment” and “do it better” in the middle of the night.

Today’s segment sleepers are likely not too attuned to the ancient practice they’ve inherited. In fact, they’re a bit self-conscious to their habits, considering segmented sleep died out at the end of the 1800s, when artificial lighting pushed bedtimes back. But many segment sleepers have picked up the practice out of a mix of convenience and necessity.

Consider an insomniac who needs to be at his office before 8 p.m. — if he’s laying there at three in the morning, wide awake, he’s desperate to get back to sleep. He knows he only has a few more hours of rest before he has to hop in the shower, get dressed, eat breakfast and catch the train to work.

But the pandemic has erased this script. Once an insomniac picks up segmented sleep, the pressure’s completely off. He can turn on his reading light and buzz through a few chapters, or head downstairs to grab himself some water, or sit in a chair and listen to music. There’s no need to pump himself up with melatonin before bed, or caffeine upon waking up. He can string together seven, eight or nine hours of sleep in a different way.

Is that healthy, though? At this point, somnologists aren’t sure. The vast majority of their data on sleep comes from the last two centuries; they can’t easily contrast the benefits of our sleeping habits with those of Elizabethan England. But it’s important to remember that we’re eons ahead in terms of sleep hygiene and comfort. It’s very possible to create a bulletproof situation if you invest time and money. Back in the day, people were literally sleeping on bales of hay. It’s no wonder they woke up so often. Perhaps we shouldn’t rely on them for wellness tips.

Still, if you’re an insomniac who’s earnestly tried to improve your sleep — no phone in the bedroom, no pre-sleep snacks, your space is cool and calm — medical experts acknowledge that segmented sleep is worth a try. That’s especially if it’s reducing your stress. Just make sure to always assess your energy levels throughout the day, and take note of whether you’re crashing at work, skipping workouts or reaching for high-carbohydrate foods. Those are all signs that your medieval life hack is not working.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.